Carmelo Gallardo is one of 11 physicians who were arrested during protests staged by citizens in Venezuela on April 30, 2019. A hematologist and head of the Blood Bank of the Maracay Central Hospital, a healthcare facility located in the central state of Aragua, he was charged with the crimes of resistance to authority, obstruction of public road, and incitement, and sent to the Alayón Detention Center, where he is still being held. This is the testimony of his wife, María Pérez de Gallardo.

Photos: Family album

Photos: Family album

Angélica Valentina shed many a tear on her birthday. On May 6, 2019, neither her father nor I could be there to celebrate with her that she is 12 now. Since her father was arrested on April 30, I haven’t had the time to take care of her or her younger brother. Carmelo’s arrest has been a bitter pill to swallow for everyone, particularly for the children, who just need to see their father and ask for him every single day.

My daughter found out through social media. When one of her teachers commented that several physicians had been arrested and produced some photographs, Angélica Valentina immediately recognized Carmelo as one amongst them. My husband is a hematologist and an internist and is the head of the Maracay Blood Bank in the state of Aragua.

That April 30 he went out to protest, like so many other people did, following the call to the streets that Interim President Juan Guaidó had made alongside Leopoldo López and surrounded by military man from the highway exit to Altamira in Caracas.

He had left his parents’ house in Santa Rita. On a bicycle, which is how my husband moves around, it was nearly 6.2 miles from the protest site; that day, however, he got a flat tire while on his way, so he decided to leave his bicycle on a neighbor’s truck and continue on foot to Maracay’s Avenida Bermúdez, armed with his whistle and some signs and posters.

In the heat of the protest, a woman fainted and Carmelo went to her aid, and it was just at that moment when some men and women in civilian attire, presumably officers of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), held him down, stole his shoes and cellphone, and took him away.

Perplexed by what she had read on the Internet, Angélica Valentina came home and asked me:

“What happened to Dad?”

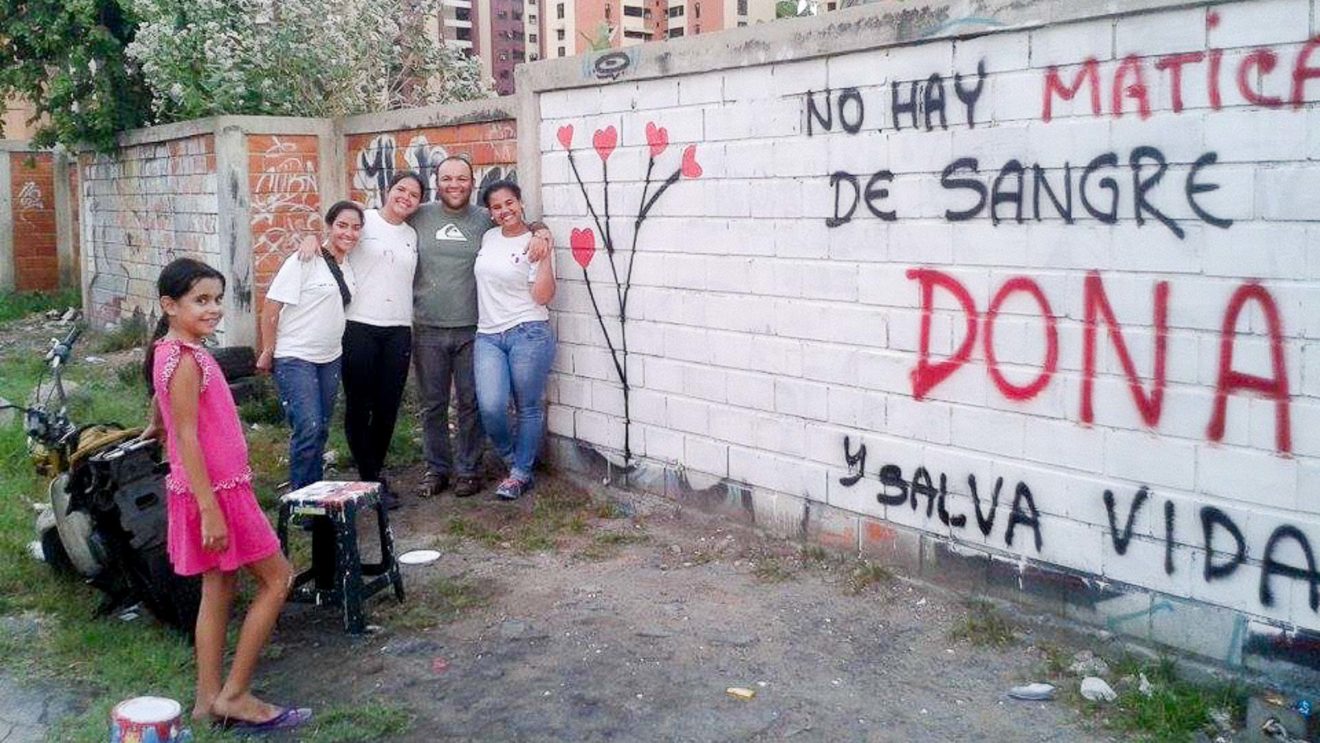

I couldn’t hide the truth from her; she’s no longer a baby, and that’s exactly what she asked me as I tried to explain what had happened. She cried. She did not understand why her father, who often took her to paint murals for blood drives, was now in prison.

“Tell Daddy that he is not alone and that I love him.”

The night that they told me about it, my youngest child was sleeping with me. Three-year-old Carmelo Andrés, although more attached to me, woke up upset and asked to talk to his father on the phone.

“Put Dad on the phone!” he demanded. It was about 9:00 p.m. when I got word of Carmelo’s arrest.

I had to tell him that his father was busy caring for sick children. Carmelo has dedicated 16 years to saving lives, especially those of children with leukemia and cancer. He has been recognized for his dedication by all of his colleagues and the friends that he has made since his days at the University of Carabobo.

I just panicked and cried my eyes out. I didn’t know what to do. I threw myself to the ground until my mother asked me to calm down. The baby was around and saw me in that state. It had been about 14 hours since we had last spoken on the phone, which was around 7:00 a.m.

“I’m going out to the streets”, he said.

“Be careful, please; act prudently; think of the children”, I replied.

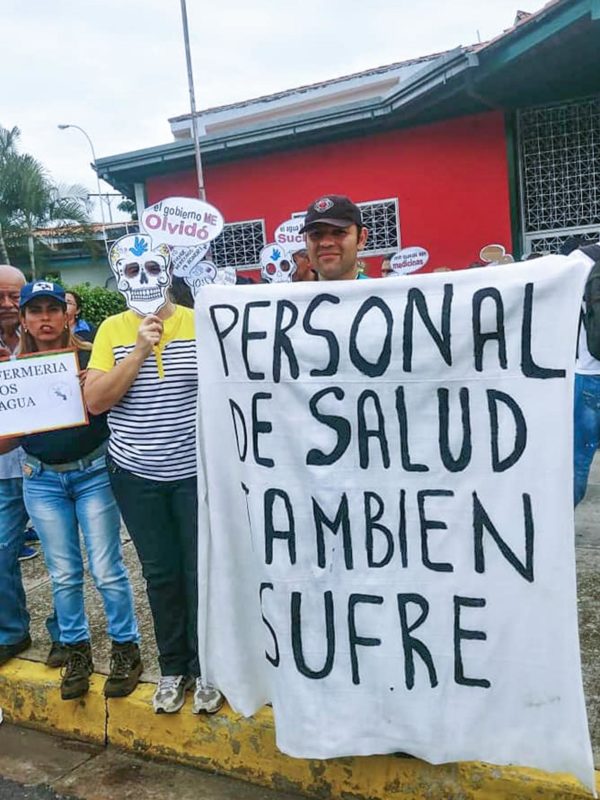

You never know how one is going to react, and although the situation we are living is no secret to anyone, there is always the fear of what they would do to people. People are disappeared. People are killed. I was worried that they could have done something to him. It was not the first time that Carmelo had exposed himself. He always held press conferences to denounce the health crisis affecting the Central Hospital, and he used to take part in peaceful protests demanding supplies, medicines and reagents to treat his patients and stock the main blood bank in the region, which he directed.

I started contacting our friends and colleagues. At that moment, I needed to know how he was, where they had him. But nobody knew a thing.

It was 11:00 a.m. on May 1 when we learned that Carmelo was alive. He had been taken to the Páez barracks, a military facility in downtown Maracay. No wonder no human rights activist or lawyer from the Aragua’s chapter of the Penal Forum had been able to locate him: the Páez barracks has never been a place to confine people detained in protests. He was kept there for three days until the night of May 2, when he was taken, handcuffed, to the Palace of Justice for the arraignment hearing. Judge Yasdeise del Valle Herrera, of the Seventh Control Court, read the charges against him: resistance to authority, obstruction of public road, and incitement, and ordered that he be confined at the Alayón Detention Center.

I wasn’t entirely surprised by his arrest. We are all at risk in this country. Besides, I have been living with Carmelo for 12 years now and I know he’s a staunch defender of human rights. He is a pacifist, and a respectful man. I was able to visit him two days later.

He cried when he saw me, but he was calm overall. He knew that we were out there fighting for his freedom. He was confident that he would come out soon, but it has been the case thus far. He’s still there. However, as long as he’s locked up, he’ll do things to help.

“Wherever I am, I’m going to practice medicine, and I have to keep doing things for my country from here”, he assured me.

The day I saw him, he gave me a list of things that he wanted me to take him. He asked me for a stethoscope, basket balls, brooms, paints, brushes and books. Carmelo had already examined the prison’s inmates, had dewormed them and had lectured them on proper hand washing; he had asked them to take their mats out in the sun to avoid mite infestation and had them engage in physical activities. He says that he will keep them busy for the duration of his imprisonment.

The paint was to paint the walls, so that the place wouldn’t look as dirty as it is now. And the books were to teach the inmates how to read and write. Carmelo is already into his 6th semester of the Education program at the National Open University, so he will make the most of his time in prison, teaching. Perhaps it is a vocation he inherited from his parents, Olga and Carmelo, both retired teachers and high-blood-pressure patients; additionally, Olga has severe difficulty hearing, and it has been two years since we could last afford paying for her heading aids.

They are hurting because their only child, their support, their pillar, their everything, has been detained. His father, who is strong as an oak, suffers quietly. They will have no consolation until they see their son free. Olga would like to see him every day, but visits are only on Wednesdays and Saturdays. She would not stop crying for a second, so much so that when she went to visit him for the first time, the inmates, moved, cried with her.

All we can do is wait until they finally take him out of there, but that does not mean that we are dropping the pressure or that we will cease to demand his freedom or taking to the streets, even though we are aware of what might happen to us for protesting. My husband knows that we are fighting for him and that he will soon be released, God willing. And once he shall have regained freedom, there will be no turning back from our decision to leave the country, that decision that we had discussed years ago for the sake of our two children.

It is not easy. It is extremely unfair that a man who has done nothing but save the lives of others should be imprisoned. Carmelo loves his profession; he dedicates himself to it without rest, and it is not me who says that: these are the words of his colleagues and co-workers.

While he spent long hours in the hospital treating children and adolescents with leukemia and other blood diseases, I was consulting patients in La Victoria and Cagua, in addition to those whom I checked as a nutritionist in the Dialysis Unit of the Maracay Central Hospital. So I had to move around a lot.

We have fallen victims to the country’s insecurity more than once. One day, we got robbed; another day, they chased me to steal my car. It was after the third time, when they asked us to pay them vacuna just to be allowed to ride our car and live in La Morita, that Carmelo decided to bike his way through the city. He was already doing so since his days as an Internal Medicine graduate student at the ‘José María Vargas’ Hospital in Caracas. He used to be overweight, but riding a bicycle helped him a lot to shed pounds. He traveled more than 20.5 miles every day, back and forth, from our house to the hospital in Maracay.

Well that’s my husband, the one with whom I share the same birthday and the same age, the one whom I would marry time and again. He is 36, and for 12 years he has devoted himself body and soul to his children. He is an exemplary father and son.

And today he is a political prisoner.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

1909 readings

I am a journalist, fortunately, because I cannot see myself exercising any other profession. I am a correspondent for Crónica Uno and for the Press and Society Institute in Aragua. I am also an active human rights defender.

Un Comentario sobre;