On June 29, 2017, a group of students from the Simón Bolívar University was detained in El Rosal by police officers who were repressing a protest march that had been called for in Caracas. The images of their arrest and subsequent transfer inside the closed cargo section of a truck were circulated on social media. The students would be released a few days later without charges. One year after the events, Patricia Rodríguez, one of the students in question, gives La vida de nos her account of her experience.

Photos: Personal Archive / Alejandro Terán / Anthony Aparicio

Photos: Personal Archive / Alejandro Terán / Anthony Aparicio

If you think about it, everything that we went through in 2017 seems so unreal that it feels like a distant memory, but one that is at the same time alive and clear.

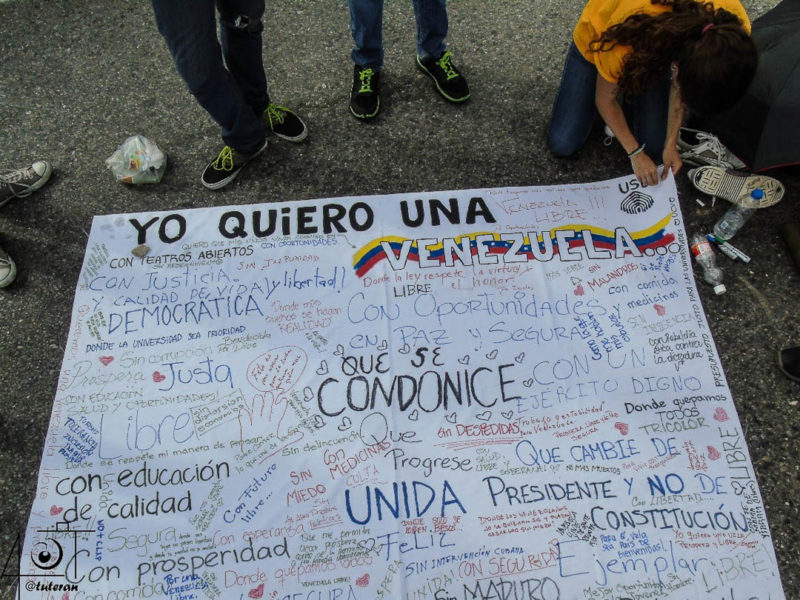

On June 29, my friends and I had planned to go to the 90th demonstration day, just as we had attended the eighty-nine previous ones. A wave of protests against the regime had been rocking the country since the beginning of April. It all made part of a routine: one would wake up, have breakfast, get ready, make sure you did not forget anything, say goodbye and go to the meeting point.

But the routine was altered that day.

Some of us had to go first to the Simón Bolívar University (USB, Universidad Simón Bolívar) for a meeting, and then we would be joining the others in Plaza Francia. A few of our colleagues at the university insisted that we not go to the march, that we would be late anyway, but we had already agreed with the others to meet there. We had to go; rather, we wanted to go.

We were on our way to the march when we read the news on Twitter: the Bolivarian National Police had raided Plaza Francia. I immediately got that sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. We phoned our friends. They had taken cover in Centro Plaza. Someone asked if it would not be better that we warned them of the raid and asked them to leave the place, but then we all decided to go where they were.

The number of people attending the demonstrations had substantially decreased and, on a rainy day such like that, it seemed even more so. Regardless, the march began. And there we were, a group of students from the USB, our shoes waterlogged and our clothes dripping rainwater, but with lots of energy and ready for a new rally.

“I brought the Venezuelan flag that belonged to my grandfather,” I said as I took it out of my bag to protect myself from the rain.

“This march is going to be good, guys. Patricia has the flag already wrapped around to her waist. She is all set for whatever will come,” joked a friend.

My grandfather was a Spaniard who arrived in Venezuela in search of opportunities and fell in love with this country. He said that his heart was spread over several countries, but that he was deep-rooted here. I do not know why I took his flag with me that day.

The plan was to go to the highway, but instead we walked along the Francisco de Miranda Avenue and, at Chacaíto, we veered down to El Rosal. “There will be repression in Las Mercedes, so people would take refuge there,” I thought to myself. However, the route changed somehow and we ended up crossing the street behind Torre Banesco to connect with the highway at the El Rosal exit.

I don’t remember how long we were there before the repression started.

The group from the Simón Bolívar University followed instructions for protests by the book: stay close to the people with the university’s flags, inside the four-point grid that we draw with them. That day, we were not enough to carry the four flags, so we only had two or three. Additionally, we had organized so that there was always a group of students resisting near the repression site, visible to the ones behind, which would give the rest of us the chance to retreat and input about what was happening ahead of us. However, this time the repression was so disproportionate and hasty that the group dispersed.

We went back down the same street. We could no longer see the guards. The teargas bombs kept falling from the sky. The plan had changed again: we would now go resist in Las Mercedes. Or so I thought.

When we arrived at the start of the street, we saw that the guards were already on the bridge of El Rosal, firing bombs mercilessly. So, we took another street. Then the plan changed again: we would go back to the Francisco de Miranda Avenue.

When we reached a parallel street, we saw people running down the avenue. If we went up, we would find ourselves face to face with the police; if we stayed put, the guards would catch us from behind.

“Here they come!” shouted a woman.

“Run!”

And run we did.

I saw the door of a building open. I hesitated whether to try to get in or keep running, but my legs were dead, so I crossed into it. I started crying in desperation, realizing that we had been locked up in a mousetrap: it was a Banco Occidental de Descuento ATM booth.

“Drop your helmets on the floor and be quiet!” shouted someone.

I was hoping we could get out as if nothing had happened. However, it was already too late.

“Everybody out, hands up in the air!” they told us.

My first contact with the police was when I asked a woman officer if she did not feel sorry for what they were doing to us. I was speechless when she replied “But, what can I do?”

I swung my bag to the front of my body and they tied up my hands with one of my shoelaces. One of the police officers opened my bag and went through it; she took out the Simón Bolívar University flags that went unused that day, as well as my Venezuelan flag… or what they would later describe in the police report as “Two yellow rags and one rag yellow, blue, and red.”

“Please, don’t take the Venezuelan flag, it was my grandfather’s,” I pleaded with the officer, crying.

The woman seemed to hesitate for a moment and, after begging her several times, she opened my bag again and put it back inside.

The people that had been trapped in Torre BOD yelled at them to let us go; in response, the Bolivarian National Police placed an active tear gas canister at the door for the gas to enter. Wasn’t it ironic? Those in Torre BOD were shouting for us, and we were shouting for them to be left alone. Both groups had our hands tied, but ours were literally.

Until the police stopped an F-350 truck.

“Patricia Pilar Rodríguez Campos, Simón Bolívar University, 25957139.”

Journalists played an important role in identifying the detainees; so, just before I got on the truck, I shouted out my full name and ID number.

They stuffed us in the truck, like hug-tied animals, and half shut the doors. The effects of the smothering tear gas bombs worsened, but somehow we were able to sprinkle our faces with water from the bottles that we carried and baking soda.

As soon as the truck started, some of us managed to untie our hands. I took my phone out of my pocket and made a first call. It was 2:43 p.m.

“Dad, listen: stay calm; they caught us, the group of the Simón. We’re all together. Do you remember the list with the phone numbers? Well, start calling.”

Taking to the streets to protest meant being aware of the risk that one was running. For that reason, I had written my dad just a few days before a list of three contact numbers in case something happened to me. I didn’t expect that I would actually have to use it.

They took us to the Bicentenario Market in Plaza Venezuela and there they moved us to a different truck. It hadn’t stopped pouring and the new truck didn’t protect us from the rain or the breeze.

I asked where they were taking us. “To El Helicoide,” they replied.

That is where the headquarters of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) and the Bolivarian National Police are located.

“Not to the SEBIN, please. Not to the SEBIN,” I prayed to myself.

Fortunately, they didn’t take us to the SEBIN section.

The view from El Helicoide is impressing. You see everything. Nevertheless, what I didn’t expect to see was some ladies from the cleaning staff crying when they saw us get in. “We’re not alone,” I thought.

“Females, to this side; males, to that side.”

They called us one by one to take our name and details and our mug shot. “Disruption of public order” read our picture.

We, the twenty-five of the 350, as we called ourselves because the model of the truck where they drove us matched the number of one of the articles of the National Constitution that we were invoking, were arrested on a Thursday. We were nineteen USB students. According to my calculations, based on previous cases, ours would not be heard until Tuesday. But I was wrong.

They took us to the Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations Corps (CICPC) that same night. It kept raining. I do not think I will ever forget the image of at least fifty homeless people sleeping on a sidewalk next to the forensic police’s headquarters. I remember feeling that time passed slowly, that it was 9:00 p.m. forever. I don’t know how long we were there, going one by one to have our data recorded, both our hands fingerprinted, and our mug shots taken “front-view, side-view, now the other side.”

We were shaking and soaking from the rain and the breeze in the truck. When we returned to El Helicoide, at about 4:00 in the morning, they took us to a kind of roofed terrace. They ordered the men to sleep on the frozen floor, handcuffed, and us, the féminas, to sleep in chairs. It was unbearably cold the whole night.

I slept for about one hour. I woke up to some news that talked about us. I wished they turned off the TV.

“FYI, these women aren’t ‘armored’, for when you rape them,” said a police officer who walked past us.

They took us to the El Llanito Forensics Medicine Division. Along the way, people stared at us, pointed at us, waved hello, sounded their car horns, and shouted. “Be strong, guys!” they said, and it was heartwarming.

On our way back, we were surprised by our relatives and friends waiting for us outside the El Helicoide’s entrance. I was happy and sad at the same time. I couldn’t help crying as I waved to my family from afar.

“Don’t cry Patty, you’re my heroine. Do not cry to them. You are a warrior!” shouted my mother as she ran next to the truck.

My mom was undergoing chemotherapy, so she couldn’t expose herself to the sun, and still… there she was, all regal with her black gloves and her hat, asking me not to cry.

When we returned, they had us sitting in the truck all day long. There was a moment when someone pointed to one of the houses in the nearby slum: there were two little girls with the Venezuelan flag upside down, waving at us, cheering us on with signs.

In the afternoon —or maybe it was in the morning, because time had stopped making sense—, we were called back one by one to declare on the events or report on abuses. They also weighed us, took our measurements, and checked that our bodies were unbruised.

By Friday night, the legal defense team of law students of the Central University of Venezuela had managed to get us sheets and blankets. Additionally, the Federation of Student Centers of the USB arranged for us to receive wet wipes, toilet paper, and menstrual pads so that we could clean up. As toothpaste, we used some mints that someone from the outside had gotten us.

That night, I slept better than the first one, but I think it was because of the news that the next day, a Saturday, we would have our court hearing.

They woke us up and rushed us back to the truck. We would not stop talking about what would be the first thing we would do when we got home. We fantasized about washing our hands, brushing our teeth, and taking a shower. I argued that the first night back home I was going to sleep with my parents. We were tired but excited. When our relatives figured out where we they had parked our truck, they began to flock in. We got to see them from afar again.

“Give him a hug for me,” said the mother of one of my friends as tears ran down her face.

We were so close, and yet so far…

At the court, they called us again, one by one, to have our details taken. As I waited for my turn, Andrew, a street boy who had been detained with us, told us a little about his life. He was 17 years old, but since he did not carry an ID with him and he had no one to demand where he was, he said he was 18 so he wouldn’t be taken to a juvenile correctional. He told us that his stepfather abused his mother and that one day, when he was only 14, he decided to defend her and charged against him, but his mother took her partner’s side and broke a bottle on his son’s head, leaving him with a scar. Ever since then, he has been living on the streets.

I was at a loss for words.

When they finished profiling everyone, we went through a small door that led to the court cells. We were now in the hands of the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB, Guardia Nacional Bolivariana).

They placed the men in one room with male officers, and us in another room with female guards. They asked us to remove our clothes, even our ponytail bands.

“Squat, spread your legs and push.”

Those were the instructions they gave us to make sure that we didn’t have something hidden down there.

There were other women in our cell; some of them were criminals, but others were there for reasons similar to ours. One woman told us that she had been detained on Wednesday. She had been caught in a trancazo [a form of demonstration where people block down the streets] of which she was not even a part: she was just buying cigarettes when the GNB arrived and snatched her as she ran. They had tried to plant evidence on her like Molotov cocktails and shields. A girl told us that she was also there since Wednesday because she had filed a claim against a GNB officer who had stolen from her. And there was another girl who didn’t even know why she was there; she had just appeared in their ‘wanted’ list and had been arrested.

The place stank of urine. The latrine was at the bottom of the cell, behind a little wall. The walls were scratched with messages and had hand marks on them. On one side you could read the word “resistance”. How many people like us had been there? How old would that message be? A few days, a few months, a few years?

The time came and they called us. When they took us out of the cell, we saw that on the cell next to ours there was the guy that they had taken away on Thursday in the first raid of the Plaza, alongside another one that had been arrested for protesting. And on the cell next to that one, there were the people of Vente Venezuela [an opposition political organization].

“Cheer up, guys. We will make it through this!” they told us.

We went upstairs and they took us to a room. They sat us on five wooden benches. Again, they called us one by one in order for us to tell them, again, our personal details and file a complaint, should we have one.

I don’t know how long we had been waiting in that courtroom when the judge arrived to inform us that the hearing had been postponed until the following day at 8:30 in the morning. I felt as everything collapsed around me. We were invaded Feelings of sadness, fear and hopelessness invaded us. Those who had not allowed themselves to break down, snapped. That night our family would not hug us. That night I wouldn’t sleep in my parents’ room.

We hugged each other and cried. It would be yet another cold night.

Since we changed trucks on Thursday, I decided to talk to every police officer, discuss their opinions, listen to their problems, and explain them what drove our fight. More than once, I was surprised to see that our opinions coincided, that they too were having a hard time and that many, not to say most of them, were not happy with what was happening. Nevertheless, after our trial was postponed, my attitude changed. I didn’t have the strength to debate. I didn’t have any hope left in me to spread.

They drove us back to El Helicoide in a white truck where the sole ventilation was the air that came in through a narrow rectangular window. It was us, the twenty-five (nineteen from the USB and other people who had been arrested for protesting) plus the guys from Vente Venezuela. The men were handcuffed in pairs: right hand with right hand. It was difficult to move and even harder to breathe. Every now and then, we moved around so that everyone could be near the narrow window at least for a few minutes. Since we were very agitated, someone proposed praying the Holy Rosary. We were through the 4th mystery when one my friends began to yell that another girl in the group had trouble breathing, that she was really dizzy. We hit the panel walls of the truck and shouted so they could listen to us. It was only then that they let us out.

On Sunday, we woke up still discouraged. They took us to the courts and we went through the whole process again: we entered a room, we got undressed, we squatted, we spread our legs, and we pushed. They separated us and us, the women, were taken to the same cell that the day before.

We began to discuss the different possible scenarios: What would happen if we were paroled on bail? They would probably have us in custody for a couple of more days, and we wouldn’t be together anymore. But there was also the possibility that we wouldn’t be released. What would happen then? It was better not to think about it.

They called us back and we went up to the auditorium where the lawyers were ready for the defense hearing.

The prosecution announced that they had no charges against us; the counsels offered their arguments, and the judge said it would take him about half an hour to deliver a decision.

The half-hour turned into three hours, and we remained seated in the auditorium. Most of us were unwell. I, like several of my friends, had a stomachache because I had not been able to go to the bathroom since Thursday. Occasionally, we tried to cheer each other up, but we could barely utter a word, out of nerves.

At some point, we heard the Venezuelan anthem. Our friends were singing it to us, and where they were finished, they shouted for us to be strong. I longed to be with them and hug them so much! There was hope again: they were out there, and soon we would be too.

I don’t think I’ve ever been as scared as I was when the judge came into the auditorium. He said that he too had been a student, that now he was doing what he had always wanted and that his job required him not to be afraid. I was desperate; he wandered so much with his words that I feared the worst, until he finally sentenced.

Unconditional Release!

We hugged each other and cried, but this time it was tears of joy.

I was last in line to get out. I could see the crowd from a distance and all I wanted to do was run away, hug my people, and thank them.

They greeted us singing the national anthem again and when we got to where they were, the crowd became one family, a single embrace, and the happiness of one and all.

That night I washed my hands, brushed my teeth, and took a bath. But, most importantly, that night I had dinner with my family and slept with my parents.

My Mom protested against the regimen whenever she could. I remember getting used to watching the news when I was only 7 years old because my parents attended all protests during the oil strike. Now, since 2014, it has been my turn. Only this year my mother had her last act of rebellion: she died on January 23.

Ma, even from heaven, you will always be my heroine.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Distinguished with a special mention in the category University Journalism of the 2019 Excellence in Journalism Awards granted by the Inter American Press Association (IAPA).

Distinguished with a special mention in the category University Journalism of the 2019 Excellence in Journalism Awards granted by the Inter American Press Association (IAPA).

1784 readings

I am Patricia Pilar Rodríguez Campos. I am a 22-year old Venezuelan, a professional ballet dancer and a Simón Bolívar University electronic engineer. In my opinion, not taking action because you think you are doing too little is the biggest mistake you can make.