Rogelio Peña turned his farm Santa Rita, in the Obispos municipality of Barinas, into a prosperous property where more than 3,000 cattle gazed and about 1 million kilos of corn and sorghum were produced on an annual basis. But in 2003, the lands were declared fallow by the Office of the State Attorney General. That same year, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled that the farm should be returned to its owner. However, almost 16 years later, the ruling is yet to be enforced.

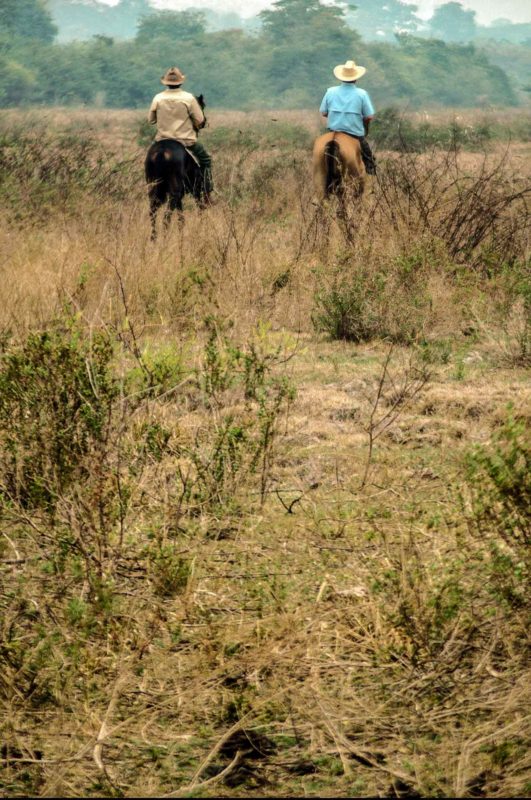

Photos: Álvaro Hernández Angola

Photos: Álvaro Hernández Angola

They say Santa Rita is a prosperous place. Although everything is flooded with water during the rainy season and summer is always hot heavy, it is a fertile and generous land. The property —which is located about 50 miles from the city of Barinas, in the Obispos municipality, in western Venezuela— extends over more than 3,500 hectares along the Santo Domingo, Masparro and Pagüey rivers.

In 1996, to buy the farm, Rogelio Peña invested his savings, took out bank loans and added the money contributed by his sister’s husband. Richard Lisch, his Austrian-born brother-in-law, didn’t think twice when he made him the business proposal: he was in love with the plains. He dreamed of one day leaving his native Europe, where he still lived, to finally settle somewhere in that peaceful tropical savannah of beautiful sunsets.

When Rogelio was still a child, his father bought La Arboleda, which is still the family estate. It is there where his love for the countryside was sown: growing up, he learned to grasp the rhythm of nature and agricultural work and farming; he enjoyed sunrises and sunsets; he felt and understood the bond that unites the plainsmen with the land and the animals. A connection that would never be broken inside of him and one that would give Rogelio the strength to defend what belongs to him when the time came.

As soon as the Universidad Experimental de los Llanos Ezequiel Zamora was inaugurated to teach courses related to agriculture, Rogelio abandoned his engineering studies in Caracas and returned to Barinas to study agricultural economics. During his high-school days at the Liceo O’Leary, he began to experience a special interest in politics, which materialized during his years as a university student. With the support of parties close to the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party, then led by Teodoro Petkoff and Pompeyo Márquez, his ticket was elected to co-government positions at the university. Later on, in December of 1995, backed by the Acción Democrática party, he was elected mayor of the city of Barinas.

When in 1996 he purchased the Santa Rita farm with his brother-in-law, Rogelio combined his work in the mayor’s office with the hard work of the plains. They were able to lay its foundations and made it operational thanks to his knowledge of agriculture and farming and to his brother-in-law’s skills as a mechanical engineer. In no time they turned it into a successful production unit: 3,000 cattle grazed in its fields and it produced around 1 million kilos of corn and sorghum a year.

But in early February 2003, a number of people escorted by an army convoy, with military on board, stationed themselves in the vicinity of Santa Rita.

They warned Rogelio that he had to leave the farm, that they were going to occupy it and that their presence there was endorsed by the National Land Institute (INTI, by its Spanish acronym). He refused to leave his cattle, his crops, his land and his work. And many of his neighbors in Santa Rita came out to support him and his workers.

For days, the military did not move from the area. They shot pellets and tear gas bombs. The crops were withering and the cattle were dying. But Rogelio and his family refused to leave. Nevertheless, after a couple of stressful weeks, he was caught and forcibly thrown off his farm.

He could not take anything of what he owned.

Carlos Mata Figueroa, then commander of the Military Garrison of Barinas, stated that the army would remain in Santa Rita on President Hugo Chávez’s orders. The people who arrived with the military, ready to occupy the property, came from two cooperatives: the ‘Batalla de Santa Inés’ and the ‘Brisas del Masparro’. Those were some of the 500 families who, at around the same time, took over the ‘Ña Soledad’, ‘El Bristero’, ‘CuritoMapurital’, ‘CuritoBajagual’, ‘La Morita’ and other neighboring farms, which combined total 31,600 hectares.

It was the same people who had claimed that the lands were fallow. For that reason, the Office of the State Attorney General, having allegedly conducted a technical survey, declared that the lands were wasteland. That is why, shortly before the occupation, the INTI awarded the new occupants the carta agraria [a provisional authorization for occupation public agricultural land while the procedures for adjudication are processed] that would give them holding of the land and which were personally delivered by Chávez.

Rogelio continued denouncing the destruction of his crops, the mistreatment of his cattle, the dismantling of his farm. He filed an action to recover his property: he first filed a complaint with the Superior Agrarian Court of Barinas, which declared it inadmissible; he then appealed the decision to the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, where he had better luck. In November 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that the remedy of amparo [an action for the protection of constitutional rights] that he requested against those who had promoted the invasion of the farm was based on legal grounds and justified: that is, it ruled against the National Land Institute and of the military garrison.

The occupants were to be evicted.

Rogelio was certain that the land would be returned to him. Soon, very soon. “I find it very difficult to believe that a subordinate officer of General Mata Figueroa would dare to follow an order that is contrary to the decision of the Supreme Court of Justice,” he thought.

He also thought that the decision in question sustained the struggle that cattle ranchers and producers waged at the time against the arbitrary acts of the national government. In 2001, via a presidential decree, the Land and Agrarian Development Law was enacted. Hugo Chávez assured that it would fight latifundismo [the system in which land is held by large estates], that the fields in the countryside would be recovered and that his government would guarantee financing and timely support to medium and small producers.

Adán Chávez, the president’s brother and president of the INTI, described the decision of the Supreme Court of Justice as “thoughtless”. He assured that no rights had been violated, that Rogelio Peña did not have title to the land and that the INTI would file a request to have the ruling of the Constitutional Chamber reviewed. “We are convinced that he took possession of those lands through the power that he exercised when he performed as mayor of the municipality of Barinas; therefore, the farm will not be returned to him,” he affirmed.

The Supreme Court of Justice declared the action filed by the INTI to be inadmissible, to which a rabid Hugo Chávez responded:

“Well, we’re not going to accept the ruling. How is it possible that a decision is made to protect bandits and landowners who stole the land and deprived the people of their rights?”

While he waited for the judgment to be enforced, Rogelio devoted himself to tilling La Arboleda, the family farm. In the meantime, he traveled regularly to Caracas: to the Supreme Court of Justice, to the Office of the State Prosecutor General, to the INTI, to the National Assembly, to the Office of the State Attorney General. He instituted contempt-of-court proceedings against the INTI and the military garrison. He filed a new action with the Supreme Court of Justice to ensure enforcement of the eviction measure.

On May 2, 2014, almost 11 years after the 2003 ruling, the Constitutional Chamber ratified the judgment: the lands of Santa Rita were to be returned to Rogelio within 20 days. In Santa Rita, and in the nearby occupied lands, there were several cooperatives that claimed to be producing livestock and cattle, criollo horses, chickens, cachamas [a class of fish], corn, bananas, rice, sunflower, cassava and sorghum. And they protested the decision of the Supreme Court of Justice. But the farm’s neighbors maintained that the property was destroyed, that there were no such crops and that the little cattle that was left grazed along the road because the perimeter fences were lying on the ground.

These lands are still beyond Rogelio’s reach.

He hasn’t even been there again. He knows about Santa Rita from the rumors that come to him. He has been told that someone is ‘half-raising cattle’, meaning that he or she gets half the proceeds from the fattening of other people’s cattle while keeping said cattle in the land for a certain period of time. He has been told that some people have settled in small plots of cultivated lands or conucos on the banks of the rivers that run through the farm, those which 16 years ago he avoided exploiting for environmental reasons.

He’s been told that his estate has been destroyed, but he is still hopeful that he’ll come back. That he will see those fertile savannahs fresh and green again, those where his brother-in-law still dreams of settling down to watch the sunset.

“From Barinas, my beloved homeland, I will leave only when God shall call me to his side.”

This text was co-written by Marian González.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

1771 readings

I am a photographer. I understand the endless possibilities for expression and communication available to those who engage in photography. That’s what I show through my work and the photographic interpretation workshops I impart, which encourage thinking.

Un Comentario sobre;