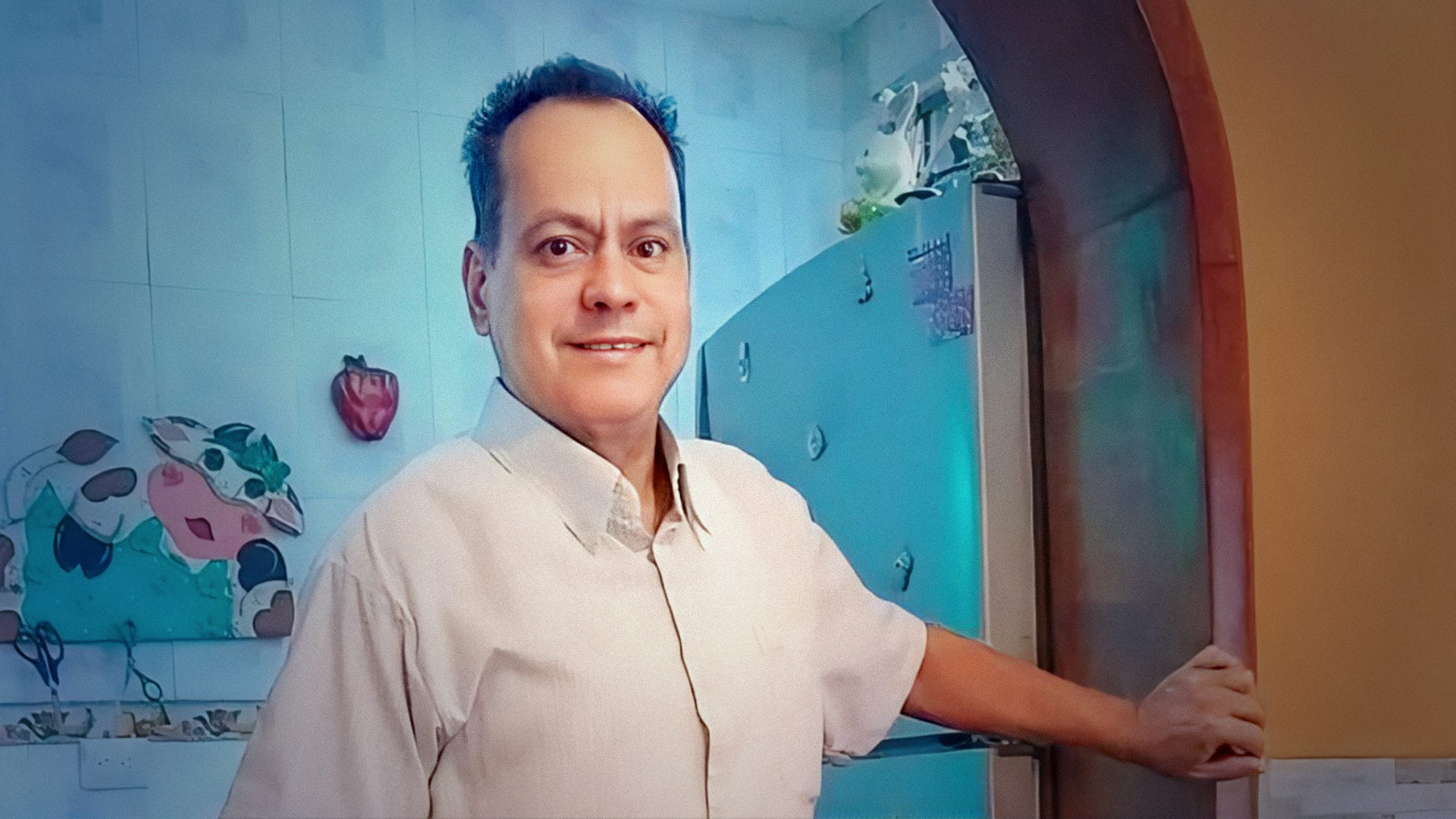

An ailing father, bitter because of the limitations ill health imposed on him; a son, yearning for the solitude he had long chosen for himself and trying to have an identity of his own; the memories of a relationship that was marked by estrangement and reconnection. Such is the thread of this story.

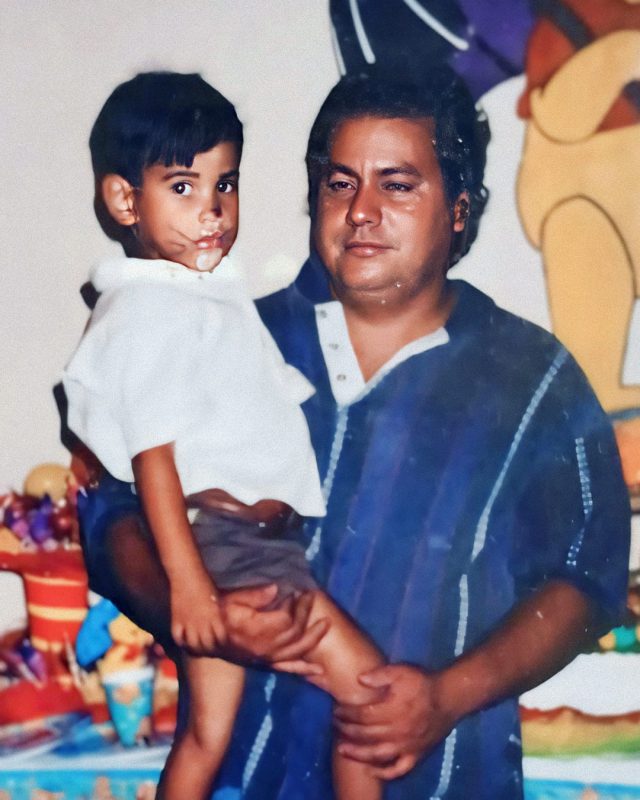

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUM

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUMCommunication was never our strong suit. Our relationship was rather aloof, on-and-off, strained, if you will. But now that a year has passed and that some days are gradually fading away from my mind, I want to have the memory of you engraved in mine, Dad, and that’s why I am telling your story.

My story. Our story.

On June 1, 2023, approximately at 9:00 p.m., you passed out. It was truly scared for the very first time. I carried you in my arms and laid you on your bed. Seeing you like that, so frail, was a bad omen I tried to chase away, as if you were seating on a powder keg. Your hypertension and diabetes could very well play an awful trick on us.

I tried to calm down. A few minutes later, we rushed you to the emergency room of the Peiférico de Pariata Hospital in La Guaira. You presented with a systolic blood pressure in excess of 400 millimeters of mercury. For an average 58-year-old man like you, a normal reading is 120; one over 140 is considered high. Your heart was pumping blood at twice the regular rate.

They managed to lower your blood pressure. At around midnight, your condition had stabilized. The on-call doctor said you needed to be admitted to monitor your blood pressure and treat an open sore you had on your left foot, which had been going for a month and had not healed despite the dressings we applied on it and the wound-healing ointments and pills we gave to you.

It was not easy for us to agree to leave you there. My mom and I considered taking you home with us because we were not sure if the hospital could provide you the level of care you needed, but my uncle, who is a nurse, warned us that if you left the premises against the doctors’ recommendations, you wouldn’t be allowed in again, and that things could definitely get worse. Needless to say, we decided to stay.

That night, they dressed your wound and put you on a bed facing the unit’s reception desk. The doctors and nurses went to rest for a while, but Mom and I stayed up all night.

You were diagnosed with diabetes in 2011, at the age of 47. Oddly enough, it was not because of your poor diet: on June 30, 2011, at 5:00 p.m. or so, when you were about to finish your turn as a heavy-duty machinery maintenance operator, the cabin of a truck whose engine you were working on flipped over and crushed you.

I still remember that day. I had just come home from school, still wearing my uniform. Things were good. I was about to graduate from high school and the following week we were going to write messages and stuff on our uniform shirts as a souvenir.

— “Carlitos, your dad was injured in an accident. He’s in the hospital,” — my aunt told me.

My mind went on full worst-case scenario mode. I was speechless for a few minutes. She asked me if I wanted to go with her to the hospital, and I shook my head no. I would later come to learn that you had sustained damage to your pancreas, which is what led to your diabetes, and to your spleen, liver, intestines, lungs, right eye socket, right collarbone, and right heel bone.

At the first hospital they took you, they said you had to wait until the next day for a CT-scan because the machine they had was not operating at the time. Fortunately, you carried medical insurance, so they drove you to a private clinic, where a surgeon said you were bleeding internally and that your body would not resist much longer. He operated on you right away.

I saw you three days later in the room they assigned you. You had a black eye, burns in half your face, and a chest tube and a vital signs monitor connected to you.

That was the beginning of our hospital journey.

I didn’t go back to school because I had to stay to take care of you. I was sixteen years old and I felt like I didn’t belong. I had been a seclusive teenager and was used to having the house to myself during the day. But now I was surrounded by strangers all the time. I had no privacy.

The urgent medical action that your internal bleeding required took the attention away from your foot fracture, but not for too long. You had a broken calcaneus, which is a small bony part of the heel that is hard on the outside but soft on the inside and acts like a shock absorber of a person’s bodyweight. Had it been treated the same day of the accident, things would have been fine. But it wasn’t. The bone healed in an unusual angle, compromising the entire joint.

As a result, you were always in excruciating pain. And you became bitter. You were in a wheel chair for months, and then on crutches. After a couple of years, you were using a cane. Going out was hard for you, as was life at home. You needed help to go to the bathroom. You couldn’t cook, drive, or go to the local food shop.

Your life had been reduced to the walls that surrounded you.

In November of that same year, you had an infection in your right foot. The antibiotic you were prescribed was quite expensive. We took you to the Doctor José María Vargas Hospital in La Guaira, which is attached to the Venezuelan Institute of Social Security, because they had it and could administer it to you. You were admitted. We were there for a month. We slept in a room with seven other patients and their accompanying relatives. Since Mom had to work, I stayed with you from Monday to Friday.

Every morning I would go down to the cafeteria or to the outdoor patio. Every night I would sit on the armchair where I slept, cover myself from head to toe with a blanket, and put on my headphones to listen to music and tune out.

I wanted to be left alone, with no one around me.

We left the hospital in mid-December.

Doctor Jonathan González, a foot and ankle surgeon we consulted, said he could operate on you and that he would be taking your case in January of 2012.

That was a year of huge changes for me. I could no longer stay with you day and night because in March I commenced my studies in Literature at the Central University of Venezuela, which are only imparted in the evenings. I had classes until 9:00 p.m., so I moved to Caracas, to an aunt’s house.

You were all by yourself while my mom worked. I would go back to La Guaira Fridays to Mondays and take you to your medical appointments whenever I could. I was by your side when you were hospitalized and when Dr. Jonathan performed surgery on you at a private clinic, but, other than that, you were on your own. At least that operation allowed you to walk again, albeit with difficulty. You didn’t need me that much anymore. Eventually, I stopped visiting you on the weekends.

I think my bitterness for having lost the solitude I had chosen for myself made me want to get away from it all.

The years passed. I did not fall behind in my studies, not even in the midst of a deep national crisis. However, in 2017, it hit the university too. I got depressed. I could not concentrate, I could not complete my assignments, I could not study… A clerical error —the college’s computer system would not recognize some of the subjects I had taken— made me take a decision I had been mulling over for months: to drop out and return to La Guaira.

We lived under the same roof again for one year.

I could confirm that we were just not compatible. We were always at odds. You never approved of my career choice. You hated that I wore my hair long. You fought with me because I used too much garlic. Every single day you would remind me that, in your opinion, I was wrong in every decision I made. I felt that, being with you, I couldn’t even figure out who I was.

You wanted me to keep you company and help you, but you were intent on forcing me to do what you wanted the way you wanted.

I was twenty-two and I wanted to reclaim my personal space and make myself heard.

I was a grown man, Dad.

Sometimes, on the weekends, I would go with my mom to an apartment she had in Yare, a town in the state of Miranda, 62 miles or so away from your place. Before I knew it, I was staying there for longer and longer. I could work remotely and it was nice to do it without being interrupted or nagged about stuff. My concentration improved. I felt free.

In 2018, I moved there for good.

It hurt not being with you, but I hurt more being around you. What a tough paradox.

I stopped calling you, I stopped going to La Guaira, I stopped being there.

Victory, my partner, moved in with me at the end of 2019. And then came the COVID-19 pandemic. I was going to visit you on March 13, 2020, but I decided otherwise because a stay-at-home order had just been issued and I knew that if I did, I would end up being locked down as before.

Thus began the longest time I had ever been without being in touch with you. I saw you again in 2021, but only for the day. My life was in another place. I didn’t belong there anymore.

Until that day in June of 2023, when I saw you faint.

Back on April 30 of that year, you tripped and fell while on the house’s flat concrete roof and got a minor cut. It would not heal. On the contrary, it was spreading.

My mom and my aunts called me and told me that you were depressed, that you didn’t talk much. They insisted that I call you because they thought that would cheer you up. I didn’t want to. Your disparaging words echoed in my head.

But, after much thought, I gave you a ring. It was at the end of May. You didn’t say much and hung up. It was a short conversation. One or two minutes, maybe.

I called you from time to time after that, but nothing changed.

I visited you once or twice.

On June 1, shortly after I arrived, you collapsed.

We took you to the Periférico de Pariata Hospital for emergency care. Unlike the social security hospital where you were admitted in 2011, this one didn’t have the medication you needed and the nurses weren’t friendly. There was no armchair, so I had to sleep on a random chair without a cushion. We shared a room with nine other patients and I had to bring you food.

My mom and I took turns taking care of you at night. It was a long week. We had to run with your test samples to other labs because the hospital had ran out of reagents. The doctors failed to dress your wound and the infection spread through your entire body.

I saw your condition gradually decline. You talked less. Breathing became increasingly difficult for you.

A week later, you collapsed. They took you to the intensive care unit. One of my aunts suggested that I should say goodbye. But how? I had never been good at talking. I had spent a lifetime holding up my feelings.

I was the last one to come in to see you.

Access to the room was restricted, but I managed to sneak in when the nurses weren’t looking. I had rehearsed a thousand times in my mind what I would say to you. I walked to your bed, I looked you in the eyes, I took your hand, and I started talking:

— “You can rest now. We are going to be fine. I love you.”

We locked eyes for a few seconds.

It may have been the most sincere exchange we had ever had, Dad.

I let go of your hand the moment the nurses noticed my presence and asked me out.

They kept saying that your condition was serious and that I should leave.

An hour later, they broke the news to me.

Now that you are dead, I have felt you closer. I have talked to you without feeling any pressure. That is perhaps why I felt the urge to write you these words and honor the conversations we never had.

Like this, in the second person singular.

This story was written within the framework of the first edition of the Training for Journalists program of La Vida de Nos.

7945 readings