Gladys Mora lives in the Villa Bahía sector of Puerto Ordaz, south of Venezuela, with her granddaughters Daniela and Sofía. From the moment the girls have been under her care, Gladys does everything she can so that they go to school. The bureaucratic barriers she has encountered have not made a dent in her resolve.

Gladys Mora lives in the Villa Bahía sector of Puerto Ordaz, south of Venezuela, with her granddaughters Daniela and Sofía. From the moment the girls have been under her care, Gladys does everything she can so that they go to school. The bureaucratic barriers she has encountered have not made a dent in her resolve.

Gladys Mora was speechless —which is so unlike her— when the teacher told her that she could not register Sofía, her 8-year-old granddaughter, in the 3rd grade. Although the teacher knows her and is well aware of the fact that the girl is under her care, she instructed Gladys go to the Ombudsman’s Office for Children and Adolescents because the authorization that Sofía’s mother had left to her name had expired. And when she tried to register Daniela, her 14-year-old granddaughter, in the 7th grade, she was told something along those lines: she could not complete the procedure because she had failed to produce the authorization that they have requested since the girl started the 6th grade the year before.

Frustrated, she went back home and brought the documents along with her. It was July of 2019.

Gladys is 55 years old and has ten grandchildren. Most of them are in La Guaira. Only Sofía and Daniela live with her in her house in Puerto Ordaz, south of Venezuela. She strives for their care. She makes sure that they are well fed, that they have clothes to wear, and that they go to school. So when she was told that she could not register them because she lacked the required authorization, she suddenly felt as though all her efforts and sacrifices were being wasted.

Gladys has a peculiar gait due to polio. Because of the disease, which she had as a child, her left leg did not develop as it should have and is skinny from the knee down; her left foot is also small and is bent out. That is why she walks with a limp. Still, she has always shown great strength of character and carries herself straight as an arrow. Her hair is long and perfectly groomed. She speaks in a strong tone, as someone who is used to giving orders.

Since 2007, she lives in Puerto Ordaz, where she moved having spent most of her life in Catia La Mar, in the state of La Guaira. She went there looking for new job opportunities and a better life for her children. After 13 years, she had already managed to turn her tin shack into a house with three bedrooms, one bathroom, a kitchen, a living-room/dining room, and a huge front yard full of fruit trees.

Sofía has lived with Gladys since 2011, when she was just a baby.

Daniela has been living with Gladys since 2018.

And, in raising them, Gladys follows her late mother’s teachings: no matter how poor a family might be, children need to have a childhood.

“Now, for example, it is their time to learn; thus, we have to make sure that they don’t to stop going to school,” she says.

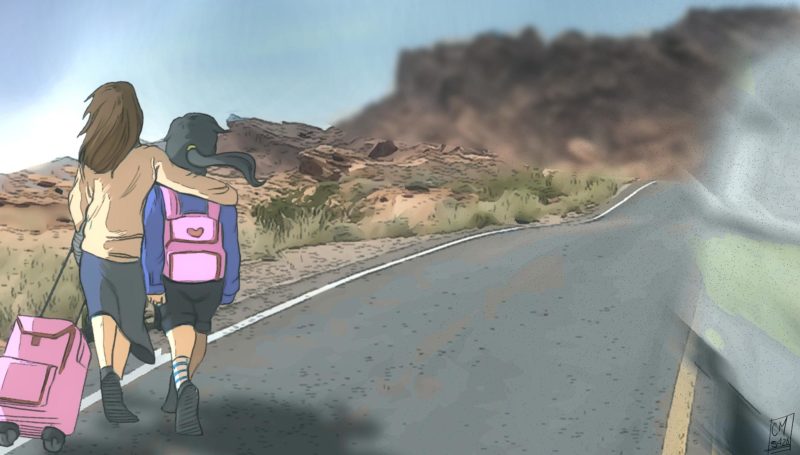

Gladys’ oldest daughter separated from the father of her two daughters Daniela and Elizabeth, and entered into a relationship with another man. Her new spouse did not get along with the girls and they were forced to go live with their father in Maracay. But the latter decided to go to Colombia and left them all by themselves, in the empty house that he owned, with no food or support from anyone. Desperate, they walked all the way back to La Guaira. They made most of their long journey on foot, and occasionally asked people for a ride. They knew they had to stay on the highway at all times and what direction to take.

They were 14 and 12 back then.

As soon as their grandma heard the news, she tried to locate them. From where she was, she involved the family in the search. That is how she learned that Elizabeth is missing. She was told that Elizabeth had travelled to Colombia, but no one knows for sure what happened to her. She was also told that Daniela was all alone wandering the streets of La Guaira. So, she sent for her with one of her daughters and ordered that the kid be taken to Puerto Ordaz. Daniela’s mother would later resume communication with her, but she never sent her any money to help with her expenses.

Sofía’s case is different. Eugenia, who had separated from her partner when Sofía was just a little kid, decided to move from Ciudad Guayana to La Guaira to make a different life for both of them. But Sofía got sick. She had a skin rash. The first thing Gladys thought was that the child’s mother was not taking good care of her, and sent for her with the same daughter who years later would go look for Daniela.

Sofía went back to La Guaira as soon as she recovered. However, it turned out she was allergic to iodine. The sea breeze made her sick. Therefore, they decided that the girl should go to Puerto Ordaz and stay there with her grandmother. Every six months, Sofía’s mother would renew Gladys’s permit to travel domestically with Sofía, and when the kid entered preschool, she acted as her representative.

In 2018, Eugenia decided to leave for Peru to work with her current life partner. If everything goes as planned, they hope to save up money and come back to the country towards the end of 2020. They help Gladys financially from Peru, but they left without anticipating the difficulties she would face in becoming Sofía’s legal representative.

That day in 2019, when she could not register her granddaughters, the people at the school told her what she needed to do.

Gladys went to the Ombudsman’s Office for the Protection of Children and Adolescents for an authorization to register the girls for the 2019-2020 school year. Sofía and Daniela started school in mid-October, when classes had already begun, because it took her almost three months to get the authorization.

She was told that, in order to act as the representative of their granddaughters, she had to obtain a colocación familiar [the granting of relative placement], which is a document that certifies that the girls have been placed with her and that she is legally allowed to raise them.

Resolutely and patiently, Gladys has been going from one place to another, filing papers for the relative placement of her granddaughters. She gets up at dawn. The money she has for food and fare she uses for copies. She is rebuked and mistreated by public servants who, instead of facilitating the process for her and show some solidarity, frown at her and make things harder.

The first office that she visited was the LOPNA office [where cases are handled under the Organic Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents] in San Felix, a city located near Puerto Ordaz. Then she had to go to the office of the prefect, apply for the proof of residence certificates, and get the signatures and copies of the IDs of the members of the Communal Council of Villa Bahia, which is the sector where she lives.

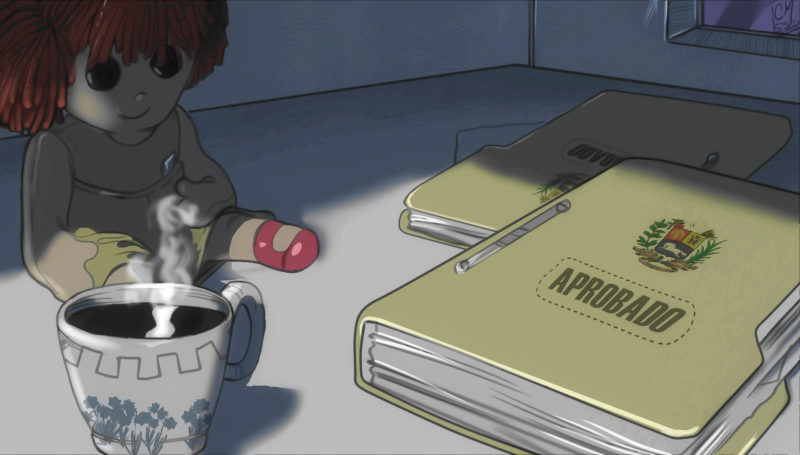

She had to put together four folders, two for each granddaughter, with copies of Gladys’ and her daughters’ IDs and the birth certificate of the girls’ mothers and those of the girls themselves. She handed in the four folders and was returned two folders stamped as received, which is evidence that she is carrying out the proceedings as instructed.

Though the list of documents is short, it has not been an easy task for Gladys, particularly because she has had to go to numerous public offices —or to the same office multiple times— in order to get them. She has to arrive very early in the morning in order to be helped, for the number of people they can receive is quite limited. She is rigorously searched in front of grumpy officials. She has been refused receipt of documents because of some issue with the signatures or stamps.

It took three months for her folders to be approved, and she was referred to the Office of the Prosecutor for Children and Adolescents.

“It has been really hard, but the girls are currently going to school. I cannot stop now,” she repeats like a mantra.

In mid-February, Gladys was finally able to file the four folders with the Office of the Prosecutor for Children and Adolescents to apply formally —at long last— for the relative placement status.

But they still have a long way to go.

Gladys and the girls are preparing for the hearing before a judge. Sofía and Daniela will have to explain why they are staying with their grandmother; they will have to tell the judge how she treats them; and they will have to confirm that they want to be with her. Gladys has no idea when the hearing will take place; once that step shall have been completed, they will have to wait from three months to two years for the ruling of the Office of the Prosecutor for Children and Adolescents.

She has discussed the hearing with the girls and has told them that they must not cry or be afraid, and that they must not lie. And that if they don’t want to stay with her, they must say so.

If she is approved the relative placement, she will be able to travel with her granddaughters anywhere in the country, apply for the ID card for the oldest one, and register them both in school, until the parents come back and take care of them again.

“So many children have been left on the streets or in the care of neighbors, and nobody cares. But I, who am fighting for my grandchildren to have a better future, wouldn’t be surprised if they asked me one day for a copy of my grandfather’s birth certificate!”

She is confident that she will be granted the request. She is confident that she will manage to have her granddaughters legally registered and studying. She is also confident that she will get her social security pension without having to pay a gestor [sort of a ‘private paperwork agent’], or open the bank account she needs for her daughter to send her dollars from Peru without having to pay a commission to convert them to bolivares and have them deposited in bolivares too

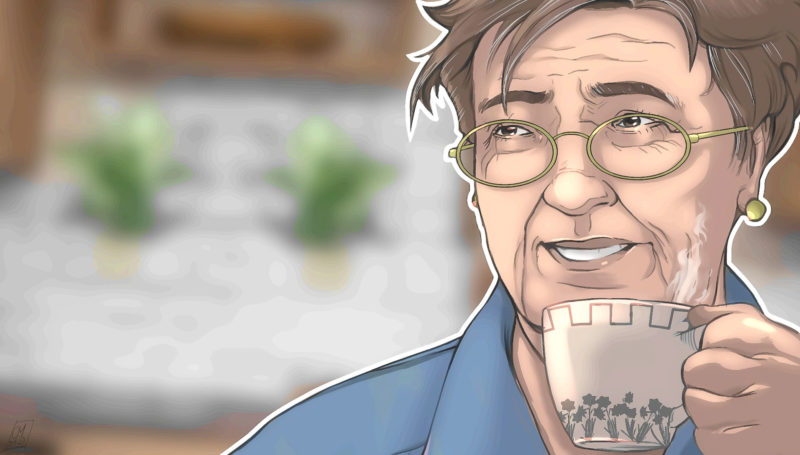

The day she filed the folders with the Office of the Prosecutor for Children and Adolescents, she said, over coffee with a neighbor:

“The attorney told me that, while we wait for a response to our petition, they are going to issue a temporary LOPNA authorization to my name so that I can perform as the girls’ representative, apply for Daniela’s ID, and finally be able to travel undisturbed to La Guaira to visit my old man. As far as I am concerned, they can take as long as they want…!”

She looked triumphant. She had a huge smile on her face.

* The names in this story have been changed in order to protect the family’s privacy.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

1813 readings

I am, I can and I have. I love walking barefoot. I am a journalist, and I would be one again. I enjoy cooking, talking and sharing with friends over a cup of coffee. I love my parents and I honor my ancestors because, thanks to them, I am, I can and I have. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

Un Comentario sobre;