Rolando Sosa inherited the Fundo San Luis from his father. It sits in Calabozo, state of Guárico, right in the Venezuelan plains. He planted grass and corn and raised cattle on 200 hectares. In December of 2008, the property was broken into by people who argued it was idle land and that they were determined to put it to good use.

Rolando Sosa inherited the Fundo San Luis from his father. It sits in Calabozo, state of Guárico, right in the Venezuelan plains. He planted grass and corn and raised cattle on 200 hectares. In December of 2008, the property was broken into by people who argued it was idle land and that they were determined to put it to good use.

Rolando Sosa was in front of his house in Fundo San Luis, surrounded by some of his workers. He was briefing them on the tasks ahead, just as he did every morning before starting their workday, when one of their peers came out of the grasslands.

“Patrón, our farm has been invaded!”, he shouted.

The man was panting and sweating. Short of breath, he went on, still shouting:

“Some people broke into through the back of the grounds. I just saw them myself when I was checking on the cattle grazing in that area.”

They were all visibly shocked. Rolando’s mind went blank. Then, he was overcome with a feeling of anger and helplessness. His first impulse was to head straight there, and confront them and kick them out the lands that fed his family and those of his employees.

But he restrained himself. He tried to calm down. He figured that resorting to violence could make things worse. It was December 3, 2008. Rolando knew that Hugo Chávez’s government supported, and even encouraged, groups that engaged in similar actions; so he’d better search for legal devices to make the invaders vacate his lands.

The Fundo San Luis is located in Calabozo, a town in the state of Guárico, in the Venezuelan plains. It consists of 200 hectares and is a family estate that Rolo, as his relatives call him affectionately, inherited from his father in the 80s. Those lands meant an entire lifetime of work in the fields to him. That is where he grew up, watching his father plant crops, herd and graze calves, and harvest food not only for his family but also for other people.

From the moment he was bequeathed with the property, Rolo dedicated himself to raising cattle and sowing grass and corn. It was a job that he enjoyed. That is where he built his home. He moved to the farmhouse with his wife Jeanette and their two eldest children when they were little. Their youngest daughter was born there. That December of 2008, because of the invasion, they just did not feel the joy of the Christmas season.

Nine people squatted 100 hundred hectares. They cut the wire fence and forced their way in with a tractor. They argued that the land was idle and unproductive and that they were claiming it to put it to good use.

Rolo sought help. First, he went to Poliguárico [the state’s police], to file a complaint. He carried with him the title deeds to the property, which clearly attested to the fact that he had inherited it. He thought it would be easy to prove to the authorities that the farm was productive: all they needed to do was to stop by.

A few days later, he and the invaders were summoned by the authorities, who made it abundantly clear that the occupation of private property was a criminal offense provided for and punishable with imprisonment under the Venezuelan Penal Code. The invaders agreed to leave Rolo’s land and signed a bond whereby they undertook no to trespass the limits of the estate.

That same day they set up shop in a tent by the outer side of the fence. Since they had reported the property as idle to the National Land Institute, they would wait for the institute’s ruling there.

And time went by, until a group headed by William Lara, the state’s governor, arrived at the farm on October 2, 2009. Rolo counted at least 20 people step out of the SUVs that they parked in front of the house. Some of the vehicles posted the names of state agencies. Lara was joined by Porfirio Fajardo (the mayor of the Miranda municipality, of which Calabozo is part); Jorge Sánchez (the director of the state’s office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands); Luis Carrizales (legal counsel to the ministry); Jesús Cepeda Villavicencio (who would later be elected member of the National Assembly for the state of Guárico by the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela); José Bolaño (national coordinator of the Peasant Front Ezequiel Zamora); Fernando Colmenares (regional coordinator of the National Land Institute); and Ramón Barreto (representative to the state’s legislative council). The press team of the office of the governor was also present.

They were all dressed in red t-shirts.

They had come to notify the owners of Fundo San Luis that, from that moment forward, their lands would become the property of the State.

The news did not take the couple by surprise, not only because they were well aware that the invaders had filed a complaint the year before, but also because a friend of the family who knew people, called them and tipped them off just a couple of hours earlier. Thus, before they arrived, Rolo and Jeanette, with the help of the workers, managed to get a few animals and some work equipment out of the farm. But they had to leave the tractors, the dredges, some 300 cattle and many other belongings behind.

Rolo and Jeanette appeared to be calm, but they were enraged. They were making an effort to listen attentively to a written record that an official from the National Land Institute was reading. As soon as the official finished, Rolo addressed the governor:

“Have I done anything else these 23 years other than work?”

“This is not a debate. Please behave in a civil manner. You will be delivered the document; then the law-enforcement authorities will take over the property,” the governor answered, waving his hands and raising his voice. “End of discussion. We are exercising our constitutional authority to take possession of this lands, which belong to the Venezuelan State. The animals, the property and improvements, everything will be accounted for. Effective immediately, your farm becomes the property of the State. I hope there will be no resistance and that we don’t find ourselves compelled to use force.”

After a short pause, and in a somewhat theatrical gesture, he put his right hand to his heart and added:

“On behalf of Commander Chávez and in my capacity as a constituent, I will make sure that your rights are guaranteed.”

And they left.

Rolo, Jeanette, and their children, who could not thoroughly understand what had just happened, were petrified.

Some friends and acquaintances of Rolo showed up at the farm as soon as they heard the news, and witnessed the procedure. Others followed suit over the next few days. The producers were afraid because they knew that any one of them could suffer the same fate.

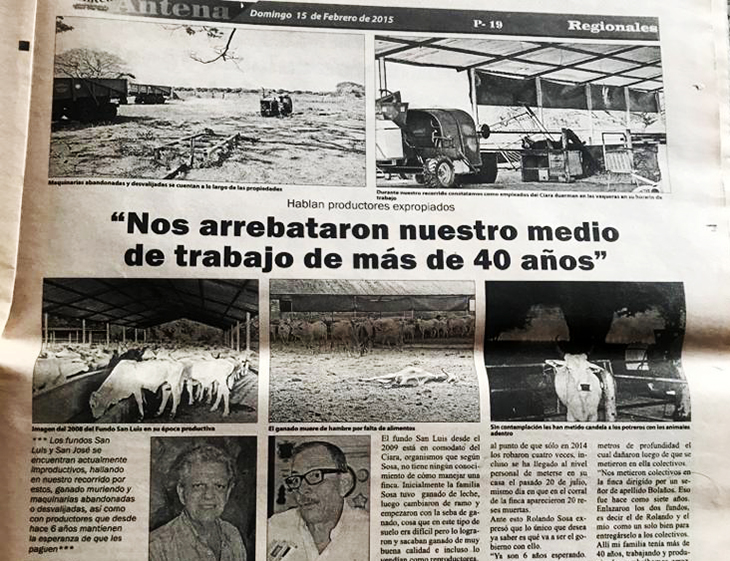

After the expropriation, the Fundo came under the administration of the Foundation for Training and Innovation in Support of the Agrarian Revolution, and many things would never be the same in San Luis. Although Rolo’s lands had been taken away from him, he could not be evicted from the house. Therefore, he and Jeanette had to live in close proximity to whom they considered their enemies, and bear witness to the devastation: thefts skyrocketed; the animals were getting sick and died emaciated; crops were lost…

They were powerless, for sure, but Rolo and Jeanette still hoped that they would be provided compensation by the State, as the governor had promised. Rolo went to the courts, hopeful to recover his inheritance, and sued the National Land Institute, which carried out the expropriation. His lawyers argued that the estate truly had thrived under its owners’ management. But on May 28, 2010, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled that their pleadings had no ground and upheld the State’s procedure.

Rolo would not give up, though. He would make the four-hour drive to Caracas to meet with the national director of the Land Institute, looking forward to reaching an agreement… to no avail. On the night of July 20, 2014, he went out to meet someone who had claimed could help him recover his lands. Jeanette stayed home, but she called him after a short while, telling him that she was hearing noises, as if someone was prowling around the house. She asked him to hurry back. When Rolo arrived at the entrance, a man caught him by surprise, his face covered, pointing a gun at him.

“Open the door,” the man ordered.

Rolo noticed that there were three more men, so he had no choice but to open the door. The robbers got in and stole whiskey, food, and three TV-sets. It was at that moment that they realized that they were facing too big a risk by staying there, so they made the decision to leave what had been their home for more than 20 years.

They surrendered what they had left.

A couple of months later, in 2015, the president of the National Land Institute asked Rolando if he wanted his farm back. Rolando was as shocked as he was outraged, and he did not know what to answer.

“That farm is yours because we have never paid you for it,” the official added.

On June 12, 2015, they were returned part of the land. The only condition, as per the president of the institute, was that they donated 114 hectares, just over half of the total land, to the Rómulo Gallegos National Experimental University, and they will own the remaining 86 hectares.

The spouses agreed, even if they felt, or rather knew for certain, that it was hugely unfair.

They still see a large part of the Fundo filled with abandoned machinery, just a few animals, and no trace of the green pastures they used to keep. They can’t help but reminisce of the times when the ground was covered with grass and the corrals and pasturelands were teeming with cattle. Jeanette treasures a photo album from back then. She flips through the pages with teary eyes, looking at photos of the gardens, of the family at Christmas or at birthday gatherings. They are together, smiling. But everything around is now very different. Shacks were built in the Fundo where people live whom they don’t even know.

Even so, Rolo and Jeanette are adamant that they want to start anew. That they want to watch their lands thrive again.Rolo looks at his wife; then he stares at the horizon, and smiles and wonders:

“Have I done anything else these 23 years other than work?”.

Sigue La Ruta del Hambre en: Mi vocación es al servicio

This story is part of La Ruta del Hambre [The Hunger Route], a publishing project developed by our network of storytellers in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

This story is part of La Ruta del Hambre [The Hunger Route], a publishing project developed by our network of storytellers in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

3913 readings

I was born in Calabozo, I graduated from the Aragua Bicentennial University and I am a radio host. I am reinventing myself in the digital era as a creative director for a local news website. We all have stories that are worth telling and that change with the eye of the beholder. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].