On the night of Saturday, March 23, 2019, Ángela Aguirre went out to a friend’s birthday party at the Club Ítalo in Puerto Ordaz, in southern Venezuela. She would never come back: her corps was found three days later, floating on the banks of the Caroní River. Ever since then, Ángel Aguirre, Ángela’s father, has not rested in his quest for justice. Over the last few months, he has incarnated the fight against femicide, of which he knew nothing about.

Pictures: Raúl Vejar Wiliams / Family album

Pictures: Raúl Vejar Wiliams / Family album

Banners made of bond paper and colored cardboard caught Ángel’s attention. Messages that read of justice, calls to nonviolence, and the name of his daughter Ángela Aguirre so many times written. It was the day of the hearing that they had been waiting for so long. The eyes of Ciudad Guayana were on them, an attention that the family had seen grow for weeks. Meanwhile, the #JusticeForÁngelaAguirre hashtag was trending nationwide on Twitter.

For Ángel and his wife Yerlis, the presence of so many people that were attentively following the case was a good thing. They didn’t want the case to slip into oblivion. Pressure was needed so that officials would do their job as they should. Or at least that was the plan. That’s what they wanted to hold on to, even in the knowledge that nothing, neither the banners nor the protests, would bring back Ángela, the 16-year-old teenager who loved to dance and sing.

What else could they do?

It was all new for Ángel Aguirre: violence against women, femicide, laws, women’s rights. He was barely getting used to the messages of support. Three weeks earlier he didn’t know a thing about that.

Three weeks earlier he was an entirely different person.

It was Saturday, March 23, 2019. In the morning, Ángela Aguirre took care of her 6-year-old brother while her parents went grocery shopping. When they came back, they all had breakfast together and a couple of hours later, they had lunch.

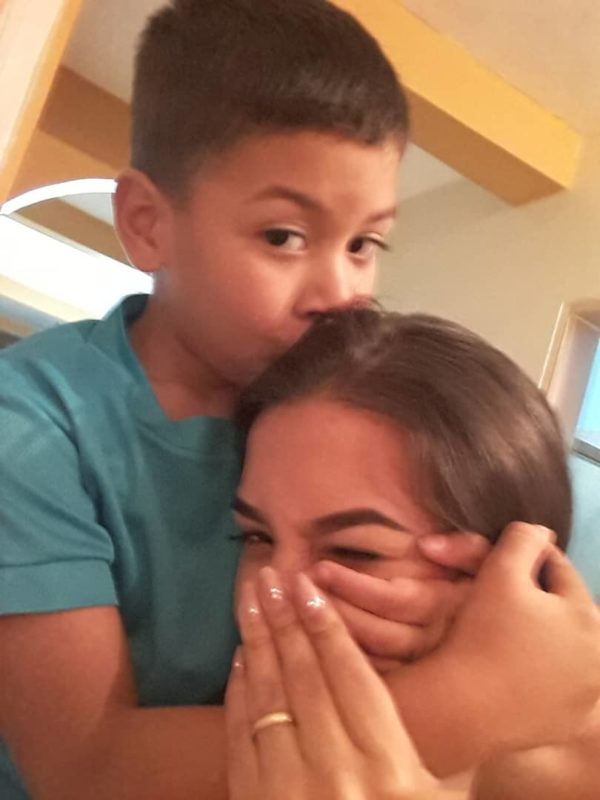

Yerlis Aguirre, née Yaguare, has a hair salon at home. Ángela loved to help her. The 16-year-old teen had taken courses and workshops in beauty and cosmetics: she knew how to tweeze and define eyebrows and blow-dry hair. She was an asset for the business. And, girly as she was, she felt comfortable. She paid a great deal of attention to the way she dressed; she put on makeup; she took care of her eyebrows so that they would look like a perfect curve in her face’s frame.

She was a cheerful young woman. She would make the occasional funny face to her mom. She danced to the tune of her favorite songs at home. She was affectionate with her little brother and very close to her older sister, with whom she shared a room. She was a good student who dreamed of becoming a mental health professional.

The family now talks about her in the past tense.

She was. She did. She danced. She dreamed.

That Saturday was the last time that they saw her.

Some of Ángela’s friends were celebrating their birthday and the she could not make up her mind as to which party to attend.

“Mom, today is Francelys’s birthday”, said Ángela.

They had been friends for many years. Her parents suggested that she go for a while, but not until late, because it would be dangerous to ride from Los Alacranes, where they lived, to Guaiparo at night.

“What is the point in going now if she is just starting to get ready and I won’t have time to share with her?”, she replied.

Then, there was a change of plans.

Another friend, José Alberto Cedeño, was turning 18 and would be celebrate it at the Italian-Venezuelan Centre in Guayana, also known as the Club Ítalo, for short.

“Hey, Dad. Today is José Alberto’s birthday too; he is inviting me to the Club Ítalo to celebrate it by the pool!

“Well, let me discuss it with your mom”

The parents agreed to let her go. They allowed their girl to go out and have fun for a while. The Club Ítalo was a gated, safe place, and had surveillance. And Ángela deserved it. She earned good grades. They trusted her very much. They knew all her friends, including José Alberto Cedeño.

“We’ll drop you at 5:00 in the afternoon and we’ll pick you up at 8:00 p.m.”, said Ángel, no ‘buts’ accepted.

Ángel Aguirre wears a short-sleeved buttoned shirt tucked in under his pressed trousers and a black belt. His scalp is covered by a shade of gray-and-white hair. When he talks about his daughter, his voice breaks beneath his harsh light-brown face. He takes his hands to his eyes, as if they were itching. He can’t hide tears. The pain overtakes him. The memory of that day persists too. Yerlis, whose hair is as dark as her daughters’, is also hurting.

They miss their Ángela.

“Justice for Ángela”, “Say No to Impunity”, “Say No to Femicide”, “Not One More”, “Let Nothing Buy Conscience”. That is what the improvised handwritten banners of the teenagers and women who joined their cause read. That Saturday, April 13, when the hearing would be held, more than 70 Venezuelan civil society organizations, including the Commission for Human Rights and Citizenship (CODEHCIU), had demanded justice for Ángela in a statement: “We demand that full access to justice be guaranteed, without undue delay, with respect for the due process of law and with judicial guarantees, with action by the judicial bodies and with due diligence, so that those responsible be punished and that justice be served for Ángela and her family”.

It was all overwhelming. Just three weeks ago, Ángel had left his daughter at the doors of the Club Ítalo.

“We will drive you there and we will pick you up”, Ángela heard from her father.

They arrived at the club’s entrance. Ángela waived goodbye, but she did not enter the Italo’s facilities right away; she walked to a vehicle that was waiting for her.

Ángel could not identify the car that was entering the club with his daughter. He had a bad feeling, but he has known José Alberto, Ángela’s friend, for three years now. José Alberto was a brown-skinned, rather short guy, and the former boyfriend of Ángela’s best friend. He seemed like a good boy.

But at 8:00 p.m. Angela would not answer her cell phone. Not at 8:30 pm, or at 9:00 pm… Something must have happened because she was not known to be disobedient. She had posted a selfie in social networks of her inside a boat that the family didn’t know about. She was wearing something that looked like a life jacket, and she was smiling.

“Ángela, if you don’t answer the phone, I’m going to pick you up at the club myself.” By 10:00 p.m. Yerlis was beginning to lose patience and left her voice messages. It was already midnight and they still had no news about her. Angelis, Angela’s eldest sister, called the birthday boy.

“I don’t know, I don’t know. She got lost”, said the young man, drowsy and clearly drunk, and he hung up and would not answer his cell phone anymore.

Everything started to crumble.

The family began to assess the options at hand. They rushed to José Alberto’s house, sad, worried, and annoyed. But they didn’t get any answers either. The birthday boy was drunk when they arrived, and he repeated a suspicious story: that Ángela had fallen from an idle boat where they would allegedly go to La Terecaya Island together with six other people at 8:30 p.m. They got distracted and then, when they turned their heads, she was gone. It was as if she had been swallowed by the river.

It all sounded absurd to Ángel. How could seven people not see what had happened to his daughter? Which boat? Why didn’t they warn the family? Weren’t they going to celebrate by the pool? Where was Ángela? Where was Ángela? Where was Ángela?!

The young man, his breath impregnated with alcohol, handed him back some of his daughter’s belongings. Among them, her smartphone, with more than 50 missed calls and a broken screen. It was already 3:00 in the morning. Ángel felt that his hands were tied. Faced with such an incoherent story, they got back in their car and drove to seek the help of relatives in the Yara Yara sector of Puerto Ordaz to begin the search and come up with an action plan. They arrived at the club’s entrance at 4:00 a.m.

“Some people came here last night seeking to remove a boat from the club, but we did not let them”, said a guard.

Seeing their worried faces, the man added:

“If the girl fell and had her life jacket on, there’s a good chance that she’s alive”.

A journalist dressed in a blue jacket, microphone in hand, approached him on that Saturday, April 13. There was a cameraman capturing the moment live with his phone. Relatives, friends and Guayaneses who had followed the case through the media were gathering at the doors of the Palace of Justice of Ciudad Guayana, in Alta Vista.

“This is the fifth time that the seven people implicated in the case arrive at this court; the indictment hearing is expected to begin in a few minutes”, the journalist said, assuredly.

Ángel, accompanied by his wife Yerlis, waited for his turn to speak. The shadows of the trees sheltered him from the sun but could not hide his nervousness. He could have never imagined that one day he would be in such a situation.

“This is something new for us”, spoke Ángel into the microphone. We do not know if our lack of knowledge is a good thing or a bad thing. We just want every question to be answered and that justice prevails.

On Sunday, March 24, the search for Ángela began.

Yerlis couldn’t stop crying and Ángel couldn’t find words to comfort her. But that didn’t stop their conviction. They contacted the aquatic rescue unit, and in the morning they went to the headquarters of the Scientific, Criminal and Forensic Investigations Corps (CICPC) in San Félix. At 7:30 a.m. they were received by an official.

“My daughter went missing while in the company of a group of adults, and it seems to me that her disappearance is very strange”, declared Ángel, fast.

“Yes, some friends called me. Some people showed up here last night”.

Ángel was perplexed.

“But how is it that everyone knows and we, who are his parents, are the last ones to know?”

“To file a complaint for a missing person you have to wait 72 hours”. That was all that the official managed to tell them.

“How is that? She went missing with a group of people. It is a question of interrogating them to know where the girl is”.

“If you want, come back later to see if the police commissioner on duty wants to take the complaint”.

But time was of the essence. They were wearing the same clothes that the night before, so they went home to wash. They returned to the Club Ítalo and the guards let them into the marina area.

A boat with members of the water rescue unit had already set sail. It was three days of search through the dark waters of the Caroní River. Some boaters lent their boats; the news began to spread on social media with every passing hour. Many round trips were made to La Terecaya Island. They searched through the areas described by the people who were with Ángela on the boat on March 23rd.

At one point, in the middle of the search, Ángel exchanged words with José Zorrilla, a 44-year-old, dark-skinned, tall man, who is José Alberto’s stepfather and the owner of the boat where her daughter had disappeared.

“Please, I need you to explain to me what happened”

“What happened is what José Alberto said happened. He was sitting with her, he turned around and suddenly the girl was gone”, he answered, categorically.

Sunday night fell. At 9:00 p.m. they suspended the search until the next day.

Ángel and Yerlis’ house has a living room with a couple of pieces of furniture that can accommodate at least eight people. That night of Sunday, March 24, it was packed with people who had joined them to plan the search. The pressure of the social networks and the contact with the media began to mount.

They could not sleep that night.

“To see the immensity of the Caroní and not to be able to find my little girl… Is she still out there in the water? Is she cold?” Ángel wondered. His 6-year-old son asked about Ángela, innocently.

“My little sister was in a boat and fell into the water and got lost”, he said.

The father’s heart shriveled: a family united, yet broken.

Would finding her, dead or alive, give them the peace of mind that they needed?

Ángela Aguirre’s body was found on Tuesday, March 26, 2019. She was floating by a riverside swimming and bathing area called El Rey.

That morning, Ángel was finalizing some proceedings to file the complaint for the disappearance of his teenage daughter. When he went back to assist with the search, he found that the club had been militarized by orders of the governor of the state of Bolivar, Justo Noguera Pietri. He realized that the case was beginning to attract a great deal of attention.

They let Ángel in with his car as soon as he identified himself. His brother-in-law was waiting for him at the entrance.

“Did you see her?” he asked.

“Did I see what?”

“The girl. They found her”.

“What?! How can it be?!” Ángel couldn’t believe it.

When he reached the shore, he found Yerlis. She was crying, inconsolable, facing the Caroní River.

In the morgue, a CICPC official approached the parents. They were still crying, surrounded by the smell of death. The man asked them for some documents. A while ago, at the river, they had not been allowed to go near Ángela. They saw her face down, from afar. They couldn’t see the body up close, but photos were already circulating on the Internet and on WhatsApp groups. As they were making them wait in the morgue, Angel complained.

“We haven’t recognized my daughter’s body! I haven’t seen my daughter’s face!”

The man entered the place where they had the body and then, after a few minutes, he came out.

“I would not advise you to see the girl. I’m not going to take away from you the right to see your daughter… to recognize her body. But I would advise you not to, because of how she is. That is not your pretty little girl”.

They had already done an autopsy on the body.

The official’s warning scared them. So it occurred to them to ask him to take photographs of parts of the girl’s body that they could recognize: three small holes in the lobe of one ear and four in the other, and a small keloid cyst at waist level, on the left side.

The photographs spoke louder than words.

The discovery of the body did not ease the family’s ordeal. After three days of hectic activity on social media, the entire Ciudad Guayana wanted to know what had happened to Ángela Aguirre.

“And why did he let her go out at night, being just a child?”, “She had it coming for going out with those ‘friends’”, “Where on earth were the parents of that underage girl?” Not all messages were of support. Revictimization was frequent during the first few days, adding to the burden of Ángel and his family.

Ángel found out about the necropsy just as the rest of the people in Guayana. The results of the forensic report had not been disclosed, but the case was already a media event.

The seven people who were in the boat with the teenager were arrested by the CICPC on March 27. That same day the director of that law-enforcement body, Douglas Rico, posted a message in his personal account on Instagram that, according to the autopsy, the cause of death had been mechanical asphyxia from drowning. He pointed out to lesions in Angela’s private parts and bruises in other areas. The father, again, was the last one to learn about said information.

Two days later, at a press conference, Rico seemed to contradict his own publication, claiming that it had been a homicide —not a femicide— and omitting sexual violence against the minor. The family canceled the funeral on CICPC orders and a second autopsy was performed on the body without parental consultation.

“Justice! Justice! Justice!”

Yells Ángel with his loved ones every time they demand that the State do its job in protecting girls, adolescents and women. After protesting at the court’s doors, he gets home and sees Angela’s photo on the wall in the living room. She is smiling. He can’t help but cry as he imagines the suffering that she must have gone through.

The authorities still bypass the Aguirre’s. The seven detainees (five men and two women) await a judicial investigation process after the April 13 hearing, which was suspended multiple times before. A prosecutor in charge of the case declined jurisdiction and was disqualified in early April after rumors of extortion and corruption with members of the CICPC, but she still have access to the file, according to complaints from family members and their lawyers. The accused were not transferred to their designated places of detention and are instead enjoying privileges in the facilities of the scientific police.

Ángela’s face gives her father strength. There are photos of him with his wife on the Internet. He feels that somehow the death of “his little girl,” as he calls her, jump started the conversation about cases like this. Tweet, hashtag, send. Ángel posts news of the case and messages calling for justice. Colorful banners are added day after day. And the Caroní River, that huge black stain that devours the mountains at night, is the major witness that he was robbed, forever, of the smile of his daughter Ángela, that which she sunk in those murky waters.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

With the support by Comisión para los Derechos Humanos y la Ciudadanía (Codehciu)

With the support by Comisión para los Derechos Humanos y la Ciudadanía (Codehciu)

2608 readings

I am a journalist from Guayana and I love literature and cinema. My heart beats for social justice, democracy and human rights causes.

Un Comentario sobre;