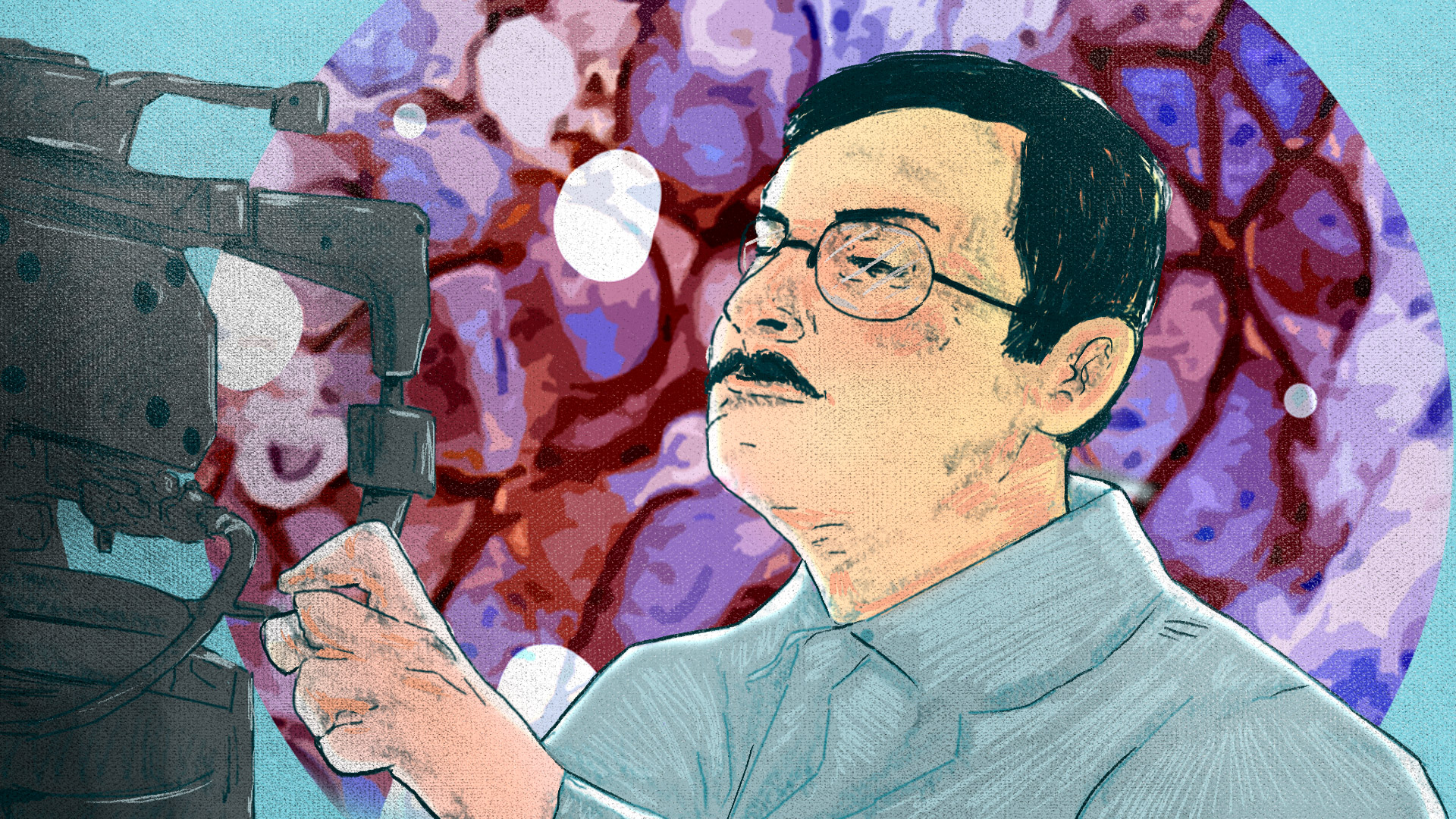

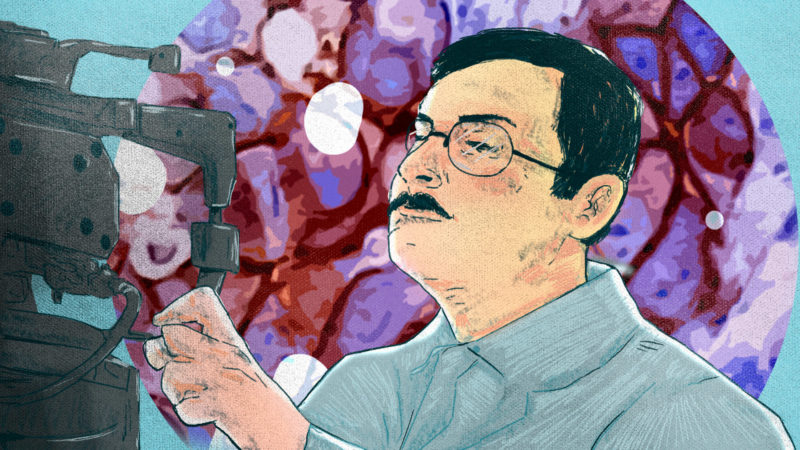

A pioneer in Venezuela in the use of immunohistochemistry —a method that allows for more accurate results in diagnostic pathology—, Dr. Jorge García Tamayo devoted six decades of his life to research and teaching. One day, he invited Elsie Picott, at the time a resident student of Universidad Central de Venezuela Anatomic Pathology Graduate Program, to join him in a research work. She has since considered him her mentor. Twenty years later, she stills asks him for advice, which he delivers, even from afar.

ILLUSTRATIONS: ROBERT DUGARTE

ILLUSTRATIONS: ROBERT DUGARTEThe first cellular ultrastructure class I attended as part of Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) Anatomical Pathology Graduate Program was taught by Dr. Jorge García Tamayo. He was a highly regarded professional who had performed as head of the Anatomical Pathology Institute, was leading advanced studies in electron microscopy, and was a pioneer in the use of immunohistochemistry in Venezuela. Not only did he stand out as an academic and a researcher, but he was also a writer and a visual artist. He certainly was an eminent figure.

Right after that class, I waited for my classmates to finish greeting him and approached him.

—“Good afternoon, Dr. Garcia,” I said in a clear and firm voice as I extended my arm to shake hands with him. “My name is Elsie Picott and I am a resident of the third year of the [anatomical pathology] graduate program at the Dr. Carlos Arvelo Military Hospital. I wanted to let you know that I loved your class.”

He looked at me as he grasped my hand and smiled.

—“Nice to meet you, Dr. Picott.”

We didn’t speak again until the next class. Much to my surprise, he approached me in the hallway at the end of his lecture.

—“Dr. Picott, would you be interested in conducting research work with me?” he asked.

Why? Why did he want me to work with him? I felt lucky. Dr. Garcia did not get along with the head of the Anatomical Pathology Institute, a man to whom the students of the graduate program, which was attached to the institute, were in some measure loyal. Not me. Although I was pursuing the UCV Anatomical Pathology Graduate Program, I was a resident at the Doctor Carlos Arvelo Military Hospital, which means that I was sort of a “free agent”. Maybe that’s why he thought I was the best option for him. And maybe that’s why he approached me that day in the hallway.

I had a thousand reasons —academic, family, personal— to decline his offer. I was in the last year of the graduate program and I had yet to complete the reports of the autopsies I had performed, which was a graduation requirement; I had to study for numerous exams and make some tweaks to my thesis. Additionally, I was living in Caracas on a temporary basis and had to go back as soon as possible to Valencia, Carabobo, to my then husband, who had been taking care of our 4-year-old son while I was studying. When the opportunity arose to take the graduate program I always dreamed of, he agreed to my moving to my parents’ house in San Antonio de Los Altos, Miranda, a 45-minute drive from Caracas, for the duration of my three-year specialization. No extensions. As soon as I finished, I had to return home. Both he and my baby boy needed me there. Needless to say, that was an obstacle for me to undertake any project because I risked getting distracted and focusing on other things and my plans falling through.

And there was also the fear that I would not live up to Dr. García’s expectations.

I thought long and hard about it. I didn’t want to say no. It was too flattering to me. My heart kept warning me loud and clear that such an opportunity to learn from one of the greats of Venezuelan pathology would never come my way again.

So I said yes.

Ecstatic, I asked Dr. García if a 2nd year graduate resident, a friend of mine from Barinas who was an excellent student, could also take part in the research. It seemed to me that she, like me, would know how to make the most of the project, and I was certain that we could help each other in the process.

He thought it was a great idea.

That is how I started in the field of immunohistochemistry. I embarked on this career at the beginning of the 21st century.

Anatomical pathology is the branch of medicine that studies the effects of diseases on organs. Anatomical pathologists analyze cells and tissues under a microscope. To examine tissue, we must stain them with cell staining dyes: hematoxylin is used for the nucleus, and eosin is used for the cytoplasm. There are other tests, including those involving histochemical analysis, that help us identify cells and tissue elements, as well as pathogens such as bacteria, parasites or fungi. But there was a need for a technique that would provide for more accurate biopsy diagnoses, which led to the development of new technologies.

That’s the origin of immunohistochemistry, a method that, as its name suggests, uses immunology, histology and chemistry to identify antigens —substances capable of inducing an immune response— through a reaction. For example, there are antigens (proteins) in tumors capable of binding chemically to an antibody, to which we add an enzyme that acts as a marker.

Despite the fact that the onset of the “brown revolution” (so called because when the antigen reacted with the antibody and its enzyme, tumor cells turned brownish and blackish in color) dates back to 1974 and the work of Taylor and Burns at Oxford University, it wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s when the technique was used to make more accurate diagnoses. It was first applied to lymphomas, which are tumors originating from blood cells.

By the end of the 1990s, Dr. Jorge García Tamayo, who had retired from the university and was privately practicing anatomical pathology, was well versed in the technique and was giving immunohistochemistry workshops to pathologists. His vocation kept him going to the UCV, though, for the university’s regulations allow retired professors to teach. It was a privilege that he was still teaching. Dr. Garcia Tamayo was, perhaps, the most experienced and renowned pathologist in the country.

The job he assigned us was to check the database of all the lymphomas he had diagnosed in his private laboratory, which he had characterized clinically and morphologically. We were to reclassify them by use of immunohistochemistry methods, which would allow oncologists to prescribe their patients a more accurate treatment plan.

In October of 2001, after much work and countless corrections by him, we presented the results of our work at the VI Venezuelan Scientific Congress of Anatomical Pathology held in Puerto Ordaz.

It was a mind-blowing experience. Although there were some questions for which we had no answers, I felt on cloud nine. Dr. García’s serene smile during the Q&A session fueled our emotions.

Not only the opportunity to speak on a subject that was still so new, at a congress with specialists from all over the country and the world, boosted our morale as graduate students: it was also a valuable occasion to disseminate the work of Dr. Garcia Tamayo, the first Venezuelan pathologist to use the technique.

The director of the graduate program at our hospital, who was a former student of Dr. García Tamayo, was very proud of the role played by two of her students; so much so that, right before every presentation, she made it clear to us that, although they were the product of the work we had done in Dr. García’s private laboratory, we were HER students. That experience really marked a before and an after for me. I felt fortunate for everything I learned.

I finished studying, graduated and returned home to Valencia. I began to affectionately call Professor García Tamayo El General [The General], like the character in the No One Writes to the Colonel novel by Gabriel García Márquez. In my opinion, the professor was a general, but this general had people who wrote to him. I wrote him via Messenger, that distant memory of a messaging service that now seems so archaic, to know how he was doing.

During my first years of practice, I wrote to him whenever I had doubts about a case. And he always had my back with an accurate response, which he interspersed with witty remarks and jokes. But life, seasoned by time and distance, slowly brought us apart, although we would occasionally talk a about pathology and literature.

Over the years, immunohistochemistry —which is used in various pathology fields to determine the nature, line and characteristics of tumor cells, differentiate benign and malignant neoplastic growths, find out about tumors of unknown primary origin, etc.— was accepted by a large number of pathologists in the country and was routinely prescribed by oncologists.

However, around the year 2012, laboratories began to increase the price of IHC tests. They had no choice: reagents have always been very expensive because they have to be imported from abroad. This was cause of great sorrow for Dr. García Tamayo. For someone as generous as himself, it was not an easy task to charge more to his patients, many of whom were low-income and could hardly pay the tests and the treatment for a disease as costly as cancer.

He was teaming up with pathologists trained in surgical pathology and immunohistochemistry.

But in 2017, as luck would have it, he got to play the opposite role in this story.

He was diagnosed with melanoma on the back of his left knee and presented a ruptured patellar tendon in his right leg. It was a very difficult case to handle in a country plunged into a health emergency. I heard that one of his daughters had managed to support him financially, which was a good thing because the salary of a retired tenured professor would have never paid for the surgeries, the physical therapy and the postoperative medical care he needed. Everything went well, but he was naturally forced to slow down, rest and undergo physical therapy for several months.

With time and room for reflection, after fruitless negotiations with public agencies in an effort to reach agreements that would allow him to lower costs and make the tests more affordable, overwhelmed by the accelerated deterioration of the healthcare system, and with a feeling that things were not going to improve despite having a team of diligent technicians, he disposed of the antibodies, supplies and equipment, dismantled his laboratory and moved part of his stuff his wife Julia’s parents’.

The move was left in the hands of assistants he did not know well, because both the doctor and his wife were in Canada, where she had been invited and where they shared for ten months as a family, recovering both physically and emotionally.

When he returned to Venezuela, he found that the 91 bound volumes where his work from 1999 to 2017 was compiled had disappeared. The only things that survived were a copy of a book with his work of the first six months of 2014, the CPU, and three hard drives with encrypted information. The woman who had been charged with the move had left for Chile, and the doctor lost all contact with her.

That was really the last straw for him, so he made the decision to retire, hang is coat on the rack permanently, and put an end to a career of more than six decades during which he published more than 100 research papers on the ultrastructure of viral, parasitic and tumor diseases and immunohistochemistry in prestigious scientific journals, both domestic and foreign; nine books, including Reflexiones de un anatomopatólogo and Más reflexiones sobre la patología —essential for those of us who practice pathology—, and thousands of entries in his blog. Six decades devoted to training dozens of professionals in the area, just like me. I am just one of many.

Having waved all work responsibilities, he moved with his wife to the UK.

Once in a while, he makes a blog post. He misses Venezuela, even if he is aware that the country where he grew up is no longer the same. But he is no stranger. In November of 2021, he was welcomed as a member of the National Academy of Medicine, where he is No. 3 for the state of Zulia. A clear-thinking and passionate person, he remains pretty active. As his former students, we can reach him by phone or email for guidance whenever we are faced with complex cases. And of course he replies. He is a beacon that is always there for us. I, for one, like many people in this country, am genuinely thankful.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

1079 readings

I am a medical doctor with a specialization in anatomic pathology. I am also a university professor. My job is to watch cells and tissue through the microscope. I read poetry and write in prose. My friends say I am a literature lover on loan to science.