Gabriela Sanchez thought she could never get pregnant again. One day, though, she found out she was expecting her second child. She and her husband decided to name him Gael Isaac. They only had him for a few hours. A woman dressed as a nurse walked into the room at the University Hospital in Mérida and snatched the baby away from them.

Gabriela Sanchez thought she could never get pregnant again. One day, though, she found out she was expecting her second child. She and her husband decided to name him Gael Isaac. They only had him for a few hours. A woman dressed as a nurse walked into the room at the University Hospital in Mérida and snatched the baby away from them.

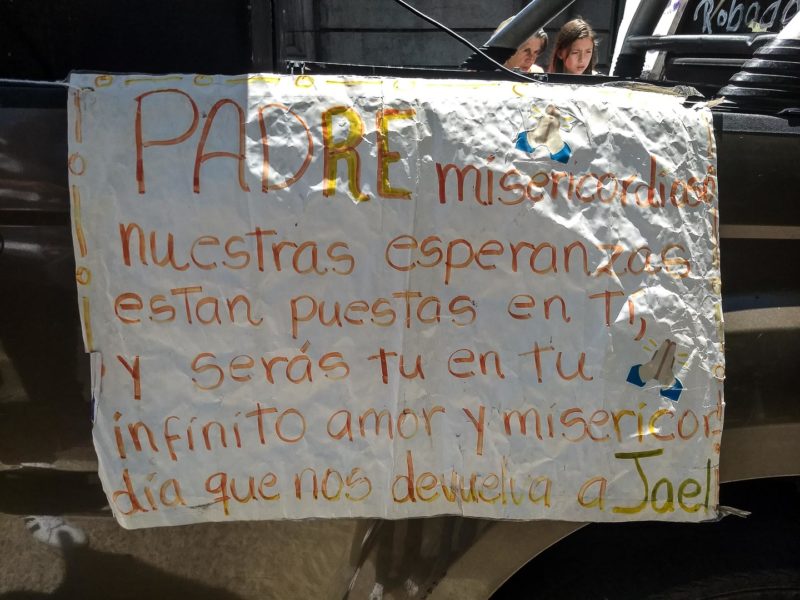

Monday to Friday, from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m., a van, or rather a truck, pulls to one side of Mérida’s Bolívar Square, on Avenida 4, just across the city’s minor basilica. It has speakers that play gospel songs and carries banners and posters that read: Return Jael Rivas, a child who was stolen from the hospital. God loves you. Return Jael. Jael, we love you.

It happens every day.

It has become commonplace.

But there is a misprint in those banners. The boy’s name isn’t Jael: it is Gael. Messages circulated on social media when news broke that a newborn baby had disappeared from the University Hospital in Mérida and people began to share the #ReturnJael hashtag. Still, for Gabriela Sánchez and Juan Rivas, the baby’s parents, the mistake is inconsequential: all that matters to them is that their missing son is found.

One day in November of 2018, way before these frantic days, an evangelical preacher on a Christian mission trip approached Gabriela in a crowd and told her:

“You will bear a child who will be coveted by the devil’s claws. But the next time I come here, you will be with your child again.”

Gabriela was startled, especially considering that, after having given birth to her daughter Amaranta Valentina, she had had trouble conceiving again. She did get pregnant twice more, once with twins and once with a boy, but in both cases she had spontaneous miscarriages.

Gabriela lives with Amaranta and her husband Juan in a house built with adobe bricks in the La Toma sector, very close to the town of Mucuchíes, in Mérida’s high moorlands; it is a place where the mountains fade away under the thick fog, hectares of frailejones can be seen just meters from the road, and the locals use oxen to plow the land. Visitors are greeted with a gentle smile and a cup of hot coffee because of the cold.

At first, Gabriela didn’t know that she was pregnant. She hadn’t grown a belly. But as soon as she began to experience morning sickness, migraines, and cravings, she decided to go to the doctor for a check-up. She travelled with Juan down to the city of Mérida for an ultrasound. At the clinic, the doctors examined her and told her that she had a uterine myoma. She needed to have surgery as soon as possible.

“A myoma? she asked, skeptical.

She had her doubts, so the next day they decided to go to the gynecologist for a second opinion. The doctor performed a new ultrasound on Gabriela and told them that she needed no surgery: Gabriela was expecting a baby. She was 6 months pregnant. With a boy.

Everyone in the family was overjoyed.

They would name the baby Gael Isaac.

The pregnancy went smoothly. On July 2, 2019, Gabriela —who had just entered her ninth month— and Juan went to city’s Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Hospital for a routine checkup. She had no symptoms that would indicate that she was about to go into labor. The hospital was a two-hour bus ride away.

When they arrived, the doctor examined her.

“Gabriela, you are four centimeters dilated,” he said. Go to the university hospital, the baby is on his way.

The doctor was referring to the major healthcare center in the state. He could not assist her there because he lacked the means to do so; also, he was not an obstetrician. Ideally, births should be attended by a specialist, especially the event of complications during labor.

The couple took a taxi back to their house in La Toma to collect the things they would need. They packed clothes for Gabriela, Juan, and the baby in a bag, and some food. That’s when she started to experience labor pains. They tried to rush back, but they found out that the gas stations in the moorlands had run out of fuel and that there was no way that they could drive down to the city.

Back in those days, people had to spend up to eight days in long lines at gas stations to fill up their tanks. And that July 2nd was no exception. For a moment, Juan and Gabriela considered to stay in Mucuchíes and have Gael there. Then they recalled the doctor’s words: “The baby’s well-being and that of Gabriela could be at risk if something unforeseen should happen.”

Enyeberth, Juan’s older brother, offered to take them. They made it to the hospital in no time. Mrs. Vicenta (Juan’s mother), some cousins, and other relatives arrived right behind them, thanks to the neighbors who kindly drove them there.

At 10:36 on the night of July 2, Gael Isaac Rivas Sánchez was born. His weight was 6.3 lbs. He was a “big, white baby.” Well, at least that is what those who saw him wrapped in blankets say.

The next day, at 9:30 a.m., Gabriela was taken up to the third floor. Juan and his mother-in-law were there, looking after her. But a nurse warned them that only one family member was allowed in the area and that visits started at noon. They were exhausted and saw that Gabriela was resting, so they decided to go to the apartment where they were staying in Mérida to fix lunch. When they returned with the food, at about 12:20 in the afternoon, they noticed something was wrong.

“Gabriela, Gabriela! Where is the baby?” Mrs. Vicenta asked.

Gabriela replied in a drowsy, tired voice, her look lost. It was as though she was not herself.

“The nurse came in, took care of my treatment, and took him away.

They left the room, agitated and unsettled, asking for the baby.

Then, a nurse came rushing in and yelled:

“What is the matter, Gabriela? They freaked me out!”

The boy’s grandmother responded:

“Can’t you see that she is drugged?!”

Gael was not in the room.

They ran around, not knowing where to go or what to do. They didn’t understand what was going on; the security officials searched everywhere and found no clues as to where the baby could be.

The child had been born just twelve hours before. They left Gabriela with a cousin and filed a complaint with the criminal investigations police (CICPC); although investigations were initiated as appropriate, the days passed and nothing new was reported.

Hours later, the mother came around. She could not tell for sure if she had been drugged, but that was her guess after all those hours she had lied there, dormant. She didn’t understand what was happening. It was beyond anything she could have prepared herself to handle. It was shocking that her son had been taken away from her.

The family, baffled as they were, searched for ways to find him; they went wherever they needed to go; they contacted whoever could help them in the process; they asked questions; they testified. They felt anger, helplessness, and despair, all at the same time.

Gabriela only got to hold her baby in her arms for 30 minutes, and Juan didn’t even meet him.

As a family, they made the decision to continue searching alongside the competent authorities. The CICPC digitized a sketch of the woman who dressed in nurse attire to kidnap the newborn. It has been glued to posts and bus stops in Mérida: a white woman with big eyes, full lips, and black hair. She could very well be any of the women who walk the streets of the city, if not for a heart tattoo that, according to the witnesses, she wears on her right forearm.

The family does not cease to ask the officers in charge of the investigations on the progress thereof. Every single day they wake up confident that they are a step closer to Gael. They voice their conviction so strongly that it actually feels they are.

The authorities have made it clear that it was not the kidnapper’s first attempt at snatching a baby the morning in question. It turns out that in Gabriela’s room there were two other women with their newborn children. The alleged nurse tried to take one of the babies under pretenses that seemed dubious to the baby’s family. Without further explanation, probably to avoid exposing herself, the snatcher left the room.

Until she had a chance with Gabriela and Gael.

“There is no such a thing as a perfect crime,” they had been told by the police.

Two DNA tests have been performed so far as part of the ongoing case. The first test was made to a child who came from Colombia in the arms of a woman who had no documents to prove his identity. The baby matched the profile of the stolen baby. However, the results revealed that it was not Gael.

Back then, a DNA tests was USD 150.00 in a clinic in the city, which they could not afford to pay, but an “angel” must have paid for it, the family says. Soon after that, another test was conducted on a baby that a married couple had brought voluntarily and in good faith, but it was not Gael either.

Every second day of the month they get together to remember Gael even more strongly. They need to remind everyone in town that the family does not lose heart and keeps waiting. One day, they circled the Bolívar Square in Mérida several times with banners as they prayed through speakers —as one, in faith— for the health and well-being of the child. On another occasion, they gathered in the square to pray with the parishioners of the evangelical church. From the truck’s platform, the pastors implored God that the baby will soon be found, while the rest of the people raised one hand to the skies and looked down, wiping their tears away.

Their faith in God is what keeps them strong in their commitment. They used to be Catholics, but it is the evangelical Christians who have supported them fervently and have commended them in their prayers during this difficult situation.

“I am hopeful that my son will appear. I know it because I feel it in my heart. God will know how to reward with his divine mercy a mother who loves her son,” says Gabriela, as she raises her hands to the skies, joined as in a prayer.

Most of the people who approach them when they go to the square cheer them up and encourage them not to give up. However, there are people who think that what they are doing is wrong, that they had no shame left to lose, and that they are disturbing the space of others. Once they were confronted by some who asked them if they didn’t feel that they were being disrespectful of God with their “fooling around” right in front of the church.

In the evenings, from Monday to Friday, when they leave the Bolívar Square, they go to the city’s communities and distribute leaflets about the Bible, asking for the return of the baby. On the weekends, they go to church to pray. When nine-year-old Amaranta, Gael’s big sister, joins them, she helps them hand them out. Sometimes, she will tell people:

“I’m looking for my baby brother who was stolen. Help us find him.”

They are now staying in Mérida in an apartment owned by Enyeberth. They have found support and encouragement in Richard, Juan’s other brother, who gives them strength and urges them not to give up on their faith that Gael will soon be found. No one forgets the words that were spoken to Gabriela in November of 2018.

They do not go to their home on the high moorlands that often anymore. If Amaranta has school, they go once a week to pick her up, and then they take her back again. They just grab the things they need, such as clothing and food, to cope with the routine that they have been forced to live.

In the thick of the crisis of the first days, Mrs. Vicenta, Gael’s grandmother, considered tying herself to a tree in the Bolívar Square; she couldn’t believe what they were going through and someone had to listen. She even thought that, in doing so, she could call the culprit’s attention. She still waits for the person who kidnapped the baby boy to call or approach them and tell them where the child is. No one in the family is looking for trouble, nor will they retaliate: all they care about is Gael.

Juan is a tough, reserved, sensitive man, and he only talks when strictly necessary. Still, he was once heard saying:

“If we ever have the incomparable happiness of getting Gael back, we will rejoice, of course, but then we will thank God at all times for the rest of our lives.”

Juan and Gabriela have a cow and two calves in La Toma. Gabriela says that one of the calves is Amaranta’s and that they’re keeping the other one for Gael when he’s older. At home, they drink milk from their grandmother’s cows and goats. When they are reunited with Gael again and can hold him in their arms, they will give it to him so that he grows up healthy and strong.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

1885 readings

I am a student of the fourth year of communication and media at the University of Los Andes. Life is made of the little things that we fail to notice or let pass us by. Close your eyes and open up your heart. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

Un Comentario sobre;