The loss of a trove of scientific documents —and the risk that may others could meet the same fate— led Pablo Emilio Colmenares and a group of specialists to create a digital repository with more than 75,000 titles related to Lake Maracaibo and its basin. They were driven by the conviction that if memory is preserved, the future can change.

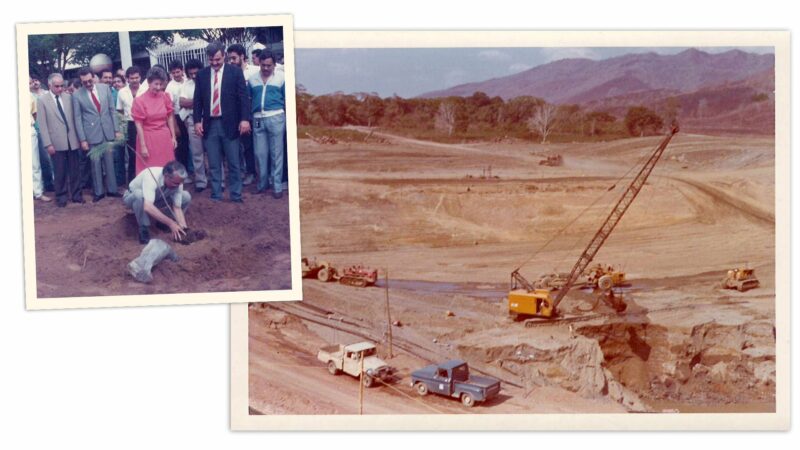

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUM

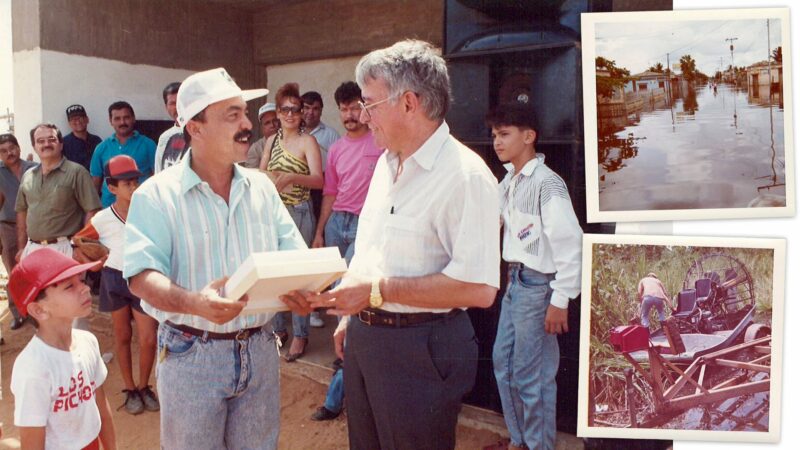

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUM

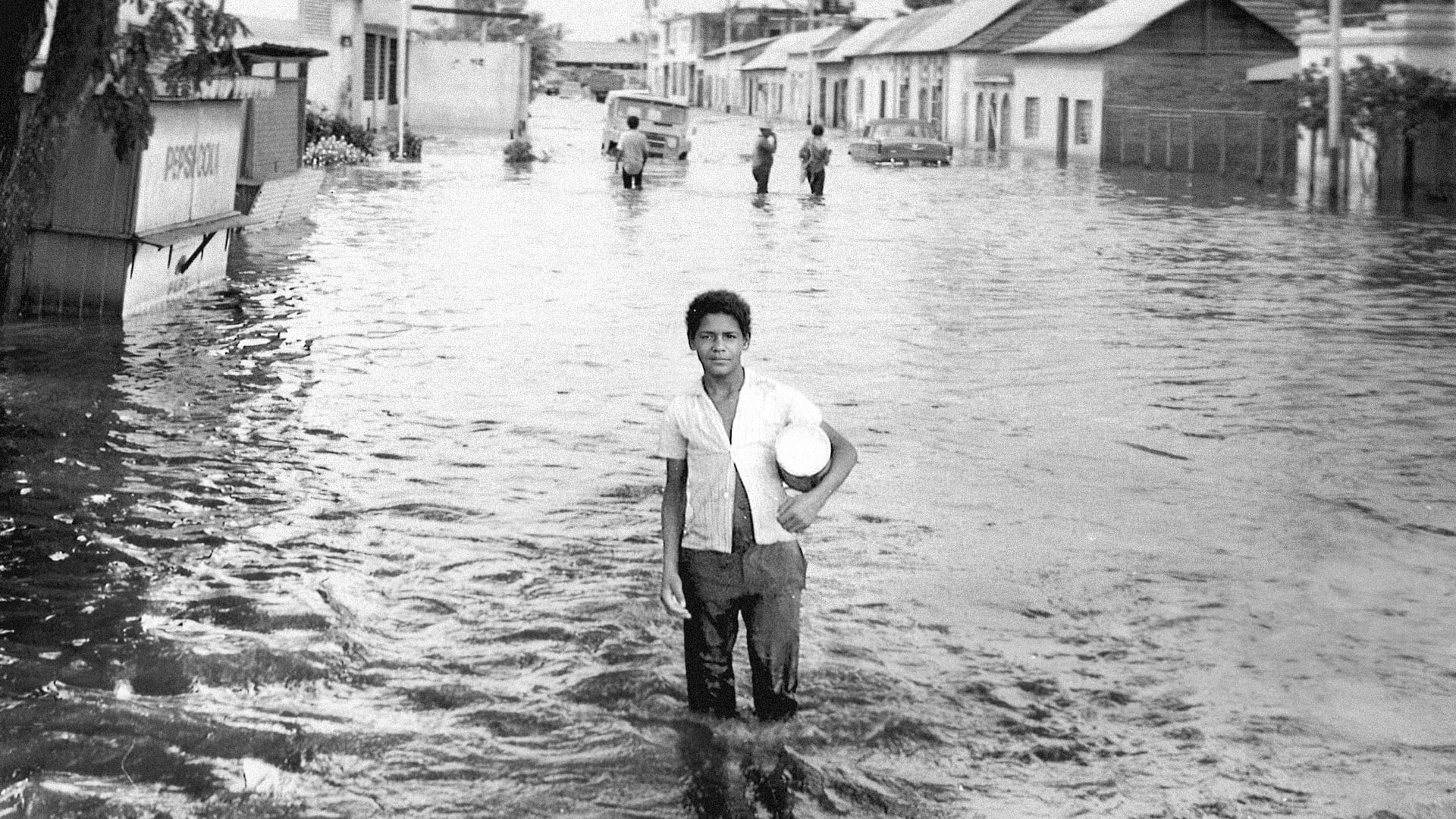

At the age of 12, Pablo Emilio had no idea what the world beyond the impressive mountains of his native Táchira looked like. That was until his parents presented him with a surprise to celebrate his having gotten through the 4th grade with honors:

— “Get ready, kid. You’re going on a trip to Caracas with Aunt Emma.”

— “Thank you! Thank you so much!” said Pablo, as he jumped up and down.

On a clear morning in August 1948, Pablo and his aunt Emma arrived at the airport in San Antonio del Táchira for the beginning of their journey.

— “You can hardly see the mountains anymore! Did you notice? Do you see the giant trees, all that forest? What a beautiful thing!” he said.

— “Of course, of course I do,” she replied, moved by her nephew’s excitement.

— “Look at all that water! Look at all that water!” cried Pablo aloud, with growing elation, as they began to fly over the basin of Lake Maracaibo.

It was as if his world was suddenly opening up before his very eyes.

It was the first time he actually saw the lake he had only seen in geography books.

Nothing else on that trip would blow his mind as much as that view.

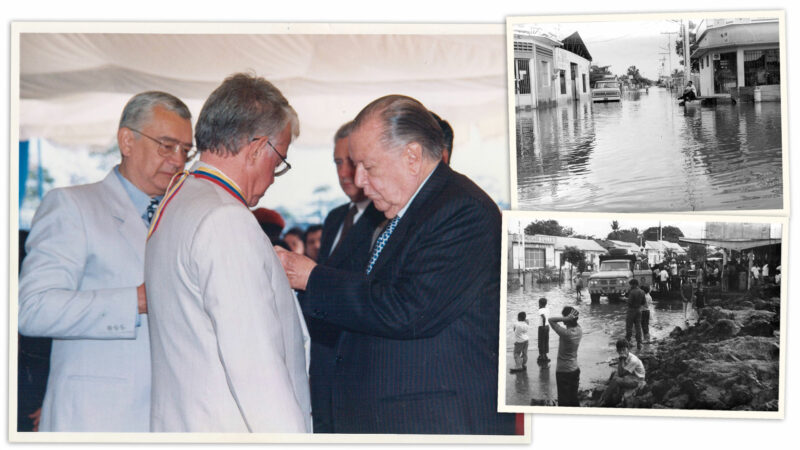

Lake Maracaibo is so large that it could accommodate the city of Maracaibo 30 times over. It is the largest lake in South America and one of the largest on Earth, and it connects to the sea through the Gulf of Venezuela. The lake’s basin covers an area of almost 122,000 square kilometers (47,092 sq. mi), which it shares with the states of Táchira, Mérida, Trujillo, and the Norte de Santander Department in Colombia. Domestic wastewater and industrial wastewater from the states of Lara and Falcón also drain into it.

The many activities that take place in its waters, and the negligence of the state, have led to its contamination with pollutants such as hydrocarbons, toxic substances, pesticides, and heavy metals, which add to its increased salinity, erosion, sedimentation and excess accumulation of nutrient deposits.

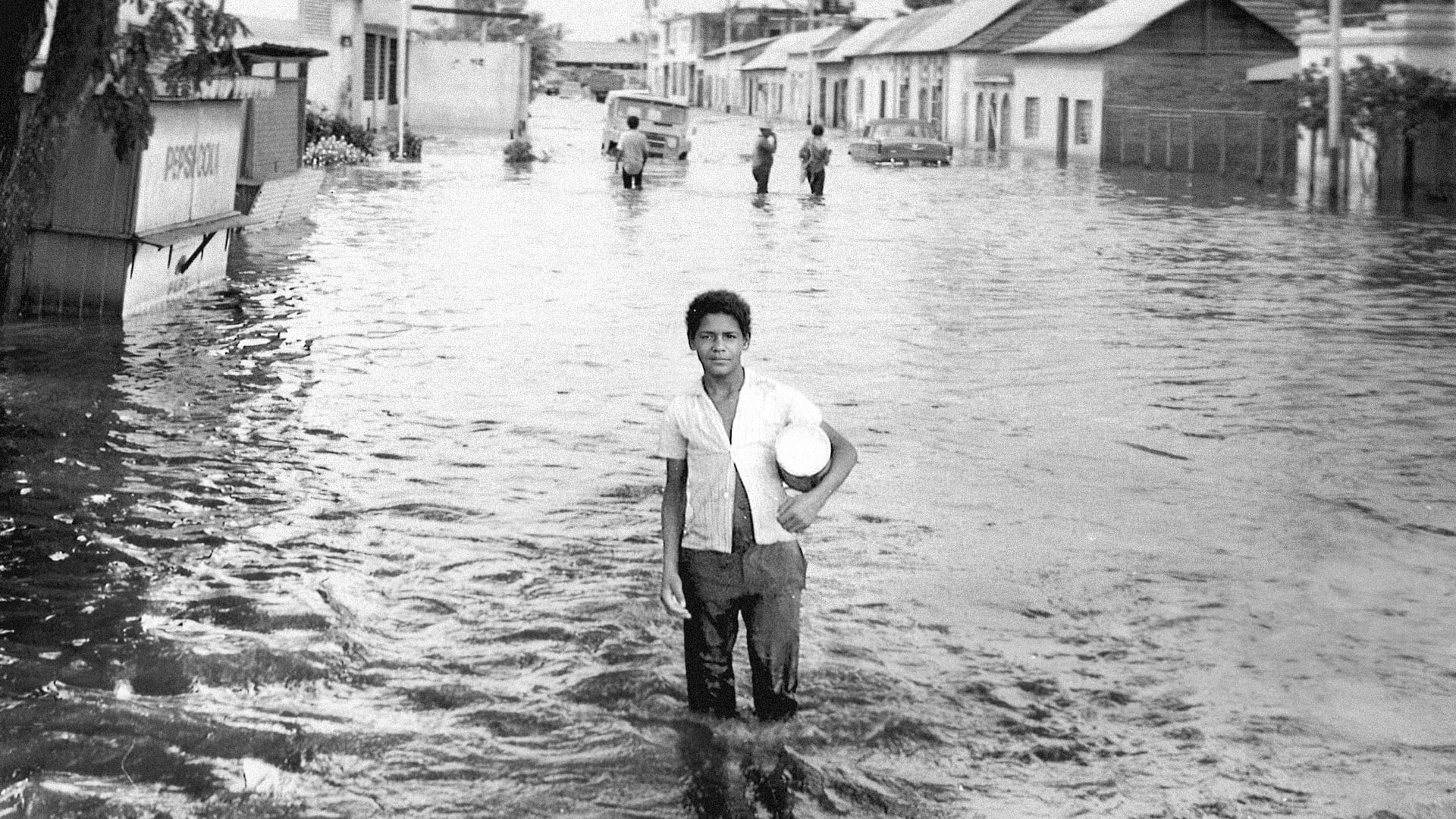

Fascinated by that captivating childhood memory, and driven by his arithmetic learning skills, Pablo Emilio Colmenares graduated as a civil engineer and majored in ground and water transportation routes at the Universidad del Zulia (LUZ). And, as an adoptive son, he worked on the southern part of Lake Maracaibo, building and maintaining dams, roads and drainage systems, and channeling rivers. Fourteen years later, he was appointed head of the Hydraulics Office and the sole authority in the area.

Venezuela was booming and he was going up in the career ladder.

In 1977, he was one of the founders of the Ministry of the Environment and Renewable Resources (one of the first of its kind in the world) and the highest representative thereof in the state of Zulia until 1983. Back then, he made it abundantly clear that officials were not to discuss politics during meetings; whoever failed to comply with that instruction was asked to leave. Their role was that of environmental experts, and they were expected to behave as such. Nothing else mattered.

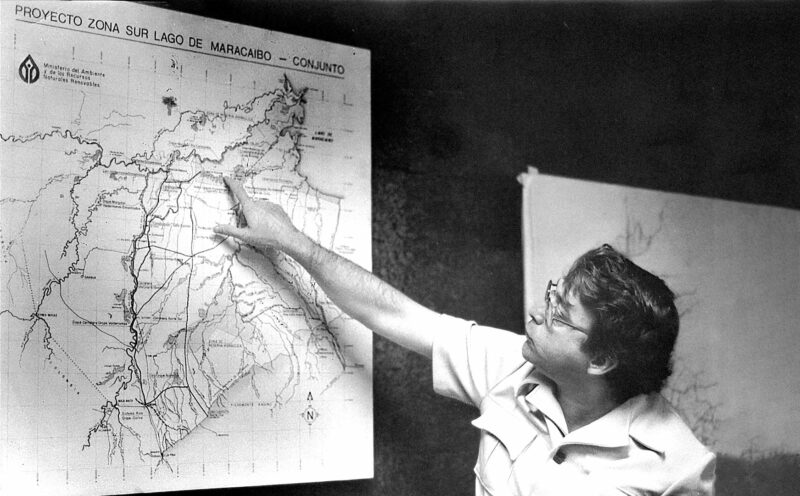

Seven years later, Pablo Emilio was appointed president of the Institute for the Control and Conservation of Lake Maracaibo (ICLAM), which he had helped establish a decade earlier. Environmental institutions were most respected in Zulia, and environmental officials were praised for their technical skills, performance, and dedication to service. Those were good times. The top experts leading the field came to the region. Great works were executed. Pablo Emilio himself was one of driving forces behind the sanitation of 330,000 hectares of the total 630,000 hectares of the program for the development of the southern part of the lake.

In 1994, he was promoted to another position and had to move to Caracas. It was a bit of a shock for him. He did not know his way around the city and was all alone and away from his wife and seven children, whom he could only visit during the weekends.

Besides, he was worried about the future, particularly after the failed coup d’état in 1992. He had a hunch that things were going to change. Regardless, he held various positions and eventually became the sectoral director general of environmental infrastructure.

The meteoric rise to power of Hugo Chávez was consummated five years later, on February 2, 1999, when he was sworn in as president of Venezuela while spreading Bolívar’s ideal. Just a few feet from the headquarters of the Ministry of the Environment and Renewable Resources in downtown Caracas, where Pablo Emilio worked, Chávez would hold massive rallies where he announced decrees, changes, and reforms.

The streets of the capital city were swarming with people and activity.

It was a turning point in history.

Much to Pablo Emilio’s surprise, and contrary to the tradition of appointing professionals in the trade, Chávez swore in Atala Uriana, a poet, essayist and Indigenous activist from Maracaibo, as minister of the Environment, a position that she would hold for only a couple of months. It marked the beginning of the instability that was to come the institution’s way: during the twenty-two years of the so-called Fourth Republic, Venezuela had ten ministers of the Environment, whereas during the twenty-four years of the combined terms of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, there had been fifteen so far.

That same year, Pablo Emilio was informed that he had been retired.

On March 19, he arrived at his office at around 7:30 a.m., as he did almost every day, and began packing his things to leave for good. He had a collection of written works that he treasured; that morning, however, he came to accept the fact that since they had been bought with state money, they were state property, and that is where they belonged. Finally, at around 11:00 a.m., he signed the office handover letter.

He felt like breaking inside when he said goodbye to his workmates, whom he respected and admired.

Disheartened, he left.

That was the end of an uninterrupted career spanning more than thirty-six years.

A month later, he handed over his other job as technical coordinator for the second stage of the Regional del Centro Aqueduct. He had no doubt that, even if he felt he was still in a position to work in the ministry, changes were irreversible.

He was leaving behind part of his legacy, including the works that allowed the union of the main islands of Los Monjes, in the Gulf of Venezuela, which were at the center of an old border dispute with Colombia in the 50s. A 40-year period where more than 90 percent of the water works and reservoirs currently existing in the country had been completed was coming to a close.

Retired and back in Maracaibo, Pablo Emilio was calm and relaxed with his family. He had missed them so much when he worked far away that he was truly at peace.

He performed as a consultant for a company that ceased operations in 2006.

One day, as he was feeling consumed by frustration, a seed began to sprout inside of him.

He was concerned that at the ICLAM, where he had worked for seven years before leaving for Caracas, research was poor and almost no works were being executed. He also worried that no progress had been made to protect the environment and that, as in many state-controlled scientific institutions, politicization was creeping and the brain drain was all but worsening.

So, he met with some friends and former coworkers of the ICLAM, who were also disquieted in the face of such an outlook, and decided to revive and an old project they had in mind. On August 24, 2004, Pablo Emilio and other scholars and retirees created ACLAMA, a civil association for the protection and rescue of the Lake Maracaibo basin.

As the years went by, they realized that the technical-environmental documentation on Lake Maracaibo and its basin was also at risk. They knew it because they tried to donate books to a couple of LUZ libraries where thousands of papers by professors and students were stored, only to find they had been vandalized and were closed and empty.

Those books and documents were exposed to damage if not kept under the proper humidity, temperature and lighting conditions.

The environmental authorities of Zulia would not admit it publicly, but the library of the former Ministry of the Environment —currently the Ministry of Eco-socialism— was and remains closed, as is the documentation center of the ICLAM (whose actual existence is still called into question by a few staff members). The digital archives of some of the media outlets in the region also disappeared, and it was not rare to find historical documents misplaced in abandoned houses.

It is true that when documentary memory is lost, ties are broken. The imminent loss of much of the technical-environmental documentation on Lake Maracaibo and its basin had Pablo Emilio and his coworkers in ACLAMA on edge. A number amongst them had authored the first scientific research works ever done in the region, and they wanted to prevent that heritage from being lost.

In 2019, they began to search for the documents and contact the authors and the relatives of those who had passed away or moved to another country to ask them to donate the material they had in their possession in order to keep it from being buried in mold and oblivion.

Now they needed to find a suitable place to store them. After visiting several institutions, they arrived at the Zulia ‘María Calcaño’ Public Library.

They didn’t think twice. It was the ideal place. At the end of 2022, they discussed the need for ACLAMA to have a physical location where the public could access the many academic, scientific and educational texts they had so painstakingly managed to preserve. Ixora Gómez, who was the president of the library, gave the thumbs-up to José Gregorio Fernández, head of the quality department, who worked on the archival concept.

ACLAMA and the ‘María Calcaño’ Public Library joined forces as they began to receive and search for more books and documents, which were to be treated, catalogued, and classified by the Department of Technical Processes. After a year, they had completed a digital repository of more than 75,000 domestic and foreign publications on Lake Maracaibo and its basin.

But they didn’t stop there: they built a room where, by use of special devices, users can have a virtual reality immersive experience of fourteen works and interact with their various components.

The Lake Maracaibo Environmental Documentation Center would thus see the light of day to provide students, researchers and the general public with the opportunity to access a collection of books, research papers, and academic, scientific, technological, cultural, and artwork documentation, and a place for knowledge socialization, culture promotion, and inspiration.

And they did it all pro bono.

The inauguration of the documentation center was scheduled for January 27, 2024, but Pablo Emilio, who had been under the weather with a cold and fever and didn’t want to make others sick, decided not to go. He called Cipriano, a friend of his and officer of ACLAMA, to preside over the act.

The ceremony started at 11:00 a.m. Pablo, who was home and alone, looked at the speech he had prepared. He reminisced of the road they had traveled and of how they had managed to put together the documents that were now for other people to use and enjoy.

— “It is an honor for me, as it would have been for Pablo Emilio,” said Cipriano in giving the speech. “We are pleased and grateful. The dream we once had is now a reality.”

Pablo Emilio Colmenares, at the age of 82, looks with a heavy heart at the Lake Maracaibo that he marveled at when he was a little kid, now more salinized and polluted than before. But he takes comfort in the fact that he took another step forward. He and the others know that if memory is preserved, the future can change.

This story was written within the framework of the first edition of the Training for Journalists program of La Vida de Nos.

407 readings