Maryflor Gamboa traveled to Santa Elena de Uairén, deep in the south of Venezuela, to participate in an activity organized by a leadership program of which she made part. She played with the children of the indigenous community of Manak-Krü for an entire week. She earned their trust, made them laugh, and learned things about them that still echo in her mind.

Maryflor Gamboa traveled to Santa Elena de Uairén, deep in the south of Venezuela, to participate in an activity organized by a leadership program of which she made part. She played with the children of the indigenous community of Manak-Krü for an entire week. She earned their trust, made them laugh, and learned things about them that still echo in her mind.

There are about 367 miles between Ciudad Guayana and Manak-Krü, a community surrounded by fruit trees and mountains in Santa Elena de Uairén. On April 15, 2019, I traveled that distance and arrived there in the middle of the night. Hundreds of stories, myths, and legends awaited me.

My excitement grew as the day scheduled for the trip approached. I was going to be in the Gran Sabana, near the Brazilian border. It was an activity organized by the Latin American Ignatian University Leadership Program, which was in turn promoted by the Society of Jesus and was aimed at training young people in leadership and social commitment. I am a student at the Andrés Bello Catholic University’s Guayana campus and I was a trainee in that program.

I always knew that I wanted to go to Manak-Krü to interact with the people there, and learn, and help. But many of my classmates dreaded the prospect. And I could understand why. A little over a month had passed since a group of people from the Pemón indigenous community had been attacked by the Bolivarian National Guard while the latter tried to keep a road open for humanitarian aid to enter the country through the border with Brazil, not far from Manak-Krü, killing two of their members and injuring 15.

Besides, the idea of waking up to the crow of roosters, in a school located deep in the south of the country, having slept in a hammock, and with the heat getting more and more scorching as the sun came up, was not a good plan for many of my fellow students.

That night, when we arrived, I knew that I had only just begun to live an unforgettable few days. Since I had previously worked as a children’s entertainer, I was in the group that would organize activities for the children of the communities of Manak-Krü and Guara Represa, which were about a 25-minute walk from each other across the mountain. My job was to make them live new experiences for a week … a week that would teach me things about them that still echo in my mind.

I thought that perhaps not many children would show up at the activity I had planned for the first day. I even feared that none would. Still, 15 minutes later, I had more than 20 kids and we started playing and having fun.

They were wary at first. Some of them, leaning back on the fence of the Fe y Alegría Manak-Krü School, just watched. After a couple of days playing games and drawing, the hugs and the ‘thank you’ became a common occurrence.

Ours was a group of six. We went through a couple of rough days when all we had was two packages of corn flour, a piece of bologna, a quarter of a kilo of cheese, and some other food that would not be enough for everyone.

And by the fourth day we had almost ran out of supplies, but the Guara Represa community always welcomed us with the smell of smoke from the fire and arepas. They served the food for us on a table. The children would watch us, approach us, hold our hands…They would share their food. Then we would head to the mountains to play. In Guara Represa and Manak-Krü there were always people who made us feel at home.

Including Mr. Jairo. Nine years ago, when his wife was pregnant with their eldest child, the couple from Mérida decided to move to the Gran Sabana in search of greener pastures, and just fell in love with what those lands had to offer.

We came back starving one day, having shared with the children all morning. All we had had for breakfast was an arepa made of toasted corn flour — or fororo. When we arrived at the school, one of our friends was waiting for us with an announcement that took us by surprise but for which we were infinitely grateful: Jairo and his family were inviting us to lunch.

I have no recollection of a meal that would have made me feel as satiated as that one.

The days passed. In the mornings, we would have activities with the children in the school’s classrooms; in the afternoons, we just wandered around and enjoyed ourselves watching their smiley, painted faces, or watching them measure their stride in races, or on their way up and down the river. They were far removed from the nightmare they had lived when some of their relatives clashed with the National Guard.

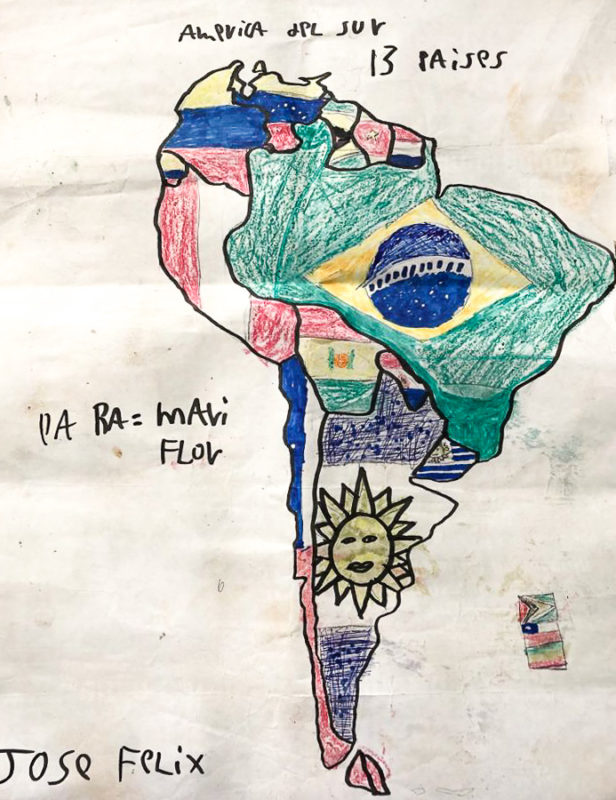

One day, instead of inviting them to play, I handed them a sheet of paper to draw on. That is when I met 10-year-old José Félix, who drew all of South America with its countries and flags. There was something in the children that I could not quite figure out or put into words, but it had me thinking at night as I looked at the myriad of stars with which the Gran Sabana showered me.

We would be leaving shortly. I asked the kids to make a drawing of their community. I wanted to know more about them; I wanted to know what is it that they wanted, or the things they longed for.

I then asked them to make a drawing of their near environment.

And then I wanted to know what their houses or the place where they lived were like.

I still remember a little girl’s voice and her drawing. She drew two figures. Two figures that stood for her and me. I remember when she told me “that is you” and that I was home to her, and that she didn’t want to go back to her house because her dad was never around and she spent the entire day all by herself.

My heart exploded with emotion as I looked at the drawing and listened to her. I was at a loss for words, so I just hugged her, kissed her on the cheek, and encouraged the children to keep on drawing.

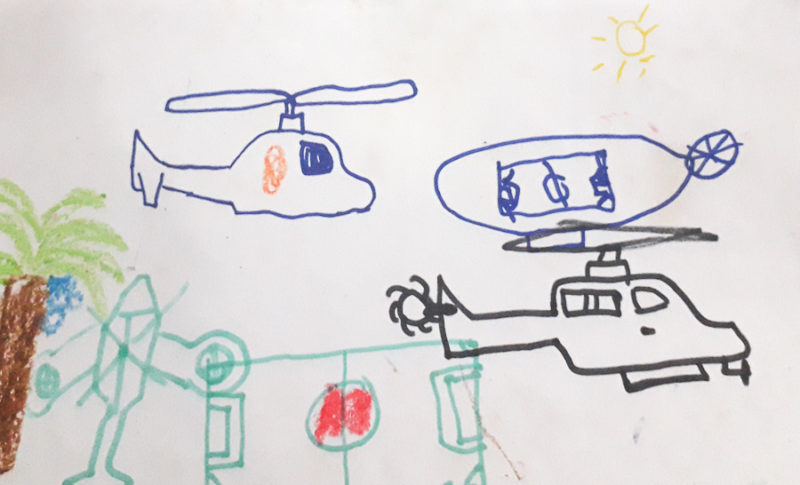

Then I asked them to make a sketch of something that they saw in their day-to-day lives. If the girl’s story left me speechless, I was shocked when I saw what they had drawn this time: guns, pistols, armored cars, and other types of weapons were the images that they chose to depict that life.

All I can recall now is that it was already time for dinner, so the children said goodbye and went home. Once they were gone, I broke down in tears. I could not understand how the children were able to describe the clash with the National Guard so well and I such detail, even if they had not lived the experience firsthand.

But, as it turned out, some of them witnessed it.

That night I could not eat.

The day before our departure, the two communities wanted to share every minute with us, even the minutes we had to rest. Thinking about what I had discovered the previous night, my desire to get to know them better grew stronger. That day, we arrived very early at the Guara Represa community because the children had a surprise for us. We were greeted by some of the adults in the community and a group of children sporting a big smile on their faces.

They had prepared a field trip for us.

They took us to a river with a very slippery slate bed, which is where they usually go to bathe. They were all happy and laughing. As the trip came to a close, both children and adults took out the cassava, rice pudding, spices, cachiri, juice, fish and other foods that they had brought to share. We were particularly sorry because we had not packed a thing to offer them. But they didn’t mind: they were most focused on serving us the food and making us feel cared for.

Back from our trip, the entire community was waiting for us at the captain’s house. He apologized for not having shared with us as much as he would have liked, and thanked us for having accompanied the children and other adults that week. He presented us with a necklace made by a grandmother from the community. Then they walked us to the top of the hill and said goodbye.

The sun was setting.

I cried again on our way back. And I saw some of my classmates cry too. That day I understood what people mean when they say that one does not need too many things to be happy. Although our reality was quite different from theirs, something had made us so equal and had brought us so close that we did not want to return to our lives in Ciudad Guayana.

When we arrived at Manak-Krü, the children were waiting for us, excited. Many had ice cream to pass around and drawings that they had made themselves. We wiped away our tears, forgot that we were tired, and continued to share with them for a couple more hours.

I find it very difficult to describe the mixed feelings I had when I went to bed that night. But if I had to choose one word to sum them up all, it would be “satisfaction.”

The next morning it was time to leave. I brushed my teeth and got dressed, and when I went out for a last walk around the community that had fed me in tough times, I bumped into the kids. I thanked them for the experience and invited them to continue studying, to support each other, and to try to help others. I cried again, hugged them, and left for my ordinary life.

On our trip home, I couldn’t stop thinking about the huge contrast between the innocence of those children’s faces and their warm embraces, and the terrible images they captured in their drawings.

Back in Ciudad Guayana, I promised myself I would return. And I hope to do so soon. But this time for more than just a visit.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

1622 readings

I am an optimist. I am curious, creative and passionate. That’s the perfect mix of words that describe me as a person. I am an old soul trapped in a young body bursting with endless joy. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

Un Comentario sobre;