During the oil strike of 2002, José Gregorio Araujo opened a small family-run Italian restaurant in Sabanetas, a mountain village on the outskirts of the city of Trujillo, in the Venezuelan Andes. Eighteen years later, they had to reinvent themselves to stay afloat.

During the oil strike of 2002, José Gregorio Araujo opened a small family-run Italian restaurant in Sabanetas, a mountain village on the outskirts of the city of Trujillo, in the Venezuelan Andes. Eighteen years later, they had to reinvent themselves to stay afloat.

José Gregorio Araujo is cooking a pasta sauce. He tastes the food, makes sure that the balance of salt is right, and turns up the heat on the stove. The house smells of cooked tomatoes, sautéed garlic, and spices. Consuelo Balza, José Gregorio’s wife, is sitting at the dining room table, sipping leftover coffee from breakfast. It is still very early, around 7:00, on an October morning in 2020. It is very cold in Sabanetas, a mountain village on the outskirts of the city of Trujillo. The icy breeze blows in through the back door of the house and Consuelo is all bundled up.

Their sons, Cristian, 25, and Gregory, 20, are on their way out to the city, approximately 11 miles from where they live, to sell the sauces that their father cooked the day before and had frozen in jars.

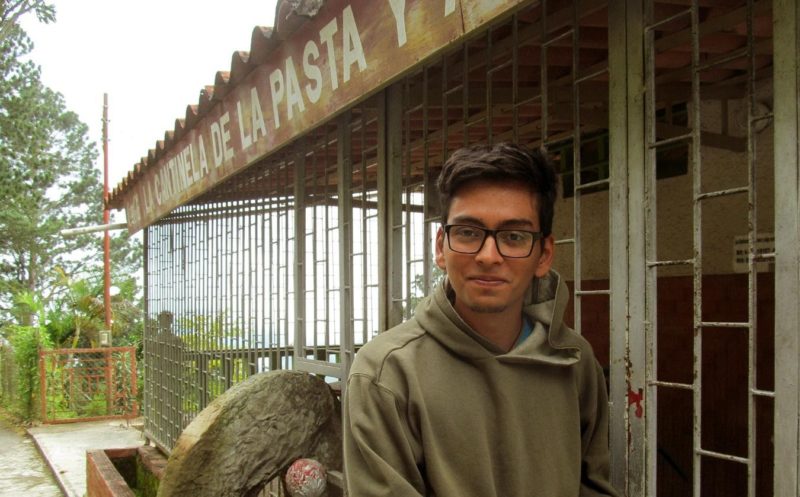

They wave their mother goodbye, cross the wet soil yard and walk up the stairs next to the patch of land where Consuelo has her blooming plants. The stairs lead to a small chalet with a gable roof, on whose façade there is a sign that reads “La Cantinela de la Pasta y Algo Más.” It is the restaurant that José Gregorio Araujo opened 18 years ago along the state road.

Getting here used to be very easy. Public transportation worked and the roads were in good shape. A lot of people would come to La Cantinela de la Pasta to eat pizzas, lasagna, raviolis, and pasta. However, the roads have deteriorated, and the Trujillo-Sabanetas route is now covered by only a few buses —the ones allotted by the regional government, made in China—, and they are always filled to capacity when they pass through their area. On the other hand, those who own a car avoid driving on such steep roads, for it is very difficult for them to fill up their tanks.

That is why the restaurant sees almost no diners now. There is the occasional customer who calls and asks to be served personally, but not as often as before. Besides, many of the restaurant patrons have left the country. And for those who have not, enjoying a plate of Italian food has become a luxury they cannot afford.

In Italian, cantinela is a place where food is stored, sort of a cellar.

The cellar is empty now.

Cristian and Gregory are waiting in front of the restaurant to catch a ride to the city with a friend with a motorcycle or maybe on a produce seller’s vehicle. Their mother looks from one of the house’s window as they finally manage to get on a truck and squeeze their way in through other locals who are also getting a lift.

As soon as they arrive there, Cristian goes straight to the La Casa del Pueblo hardware store, and Gregory to the Trujillo Shopping Center, just as they had agreed. They both have several jars to deliver. Next, they go downtown to distribute some other orders they had been placed. And then they walk for an hour to José’s, another customer.

But they are not tired. They sell nine jars of frozen sauce. It has been a good day.

And now back home, up the steep streets of Trujillo, in the midday sun. Sometimes, on these trips that have now become customary, they buy a loaf of bread stuffed with panela and cheese to fool their stomach. If they can’t catch a ride, they have to walk all the way up, and that will take them about five hours. Because it is a very steep, uphill course. Cristian, who knows firsthand how exhausting it is to make it on worn-out shoes, would rather wait for a lift.

More than once, they have had to wait as long as three hours.

The lines they have seen at the gas stations in the city of Trujillo are miles long. Their parents tell them that these are much longer than those they saw in Trujillo back in December of 2002, when the workers of the state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela brought the company’s activities to a halt, but that was 18 years ago and they were too little to remember it well.

It was around that time that José Gregorio and his wife, against all odds, inaugurated La Cantinela de la Pasta. The inauguration was quite an event in town. The premises, fit to serve 30 diners, was packed with the 50 guests that attended that day. José Gregorio and Consuelo had to juggle to accommodate them in the two sections of the restaurant so that everyone had a place at a table. Snacks were served abundantly in trays; bites of brie and blue cheese added a delicious touch to the conversation. Scotch was also passed around.

Benito Conte, the owner of the farm La Rumorosa, addressed the crowd and said how happy, pleased, and proud he was. Benito was an Italian merchant who immigrated to Venezuela. José Gregorio was in charge of the La Rumorosa’s stables and cleaned the estate’s chalet and pruned its gardens. He also tended to the seasonal crops. His pay was not enough to make ends meet, though, and the agricultural operation did not provide him with a steady income. So, José Gregorio and Consuelo engaged in other activities, like running the canteen at the town’s high school, to make some extra money while their three children were growing up… Until one day José Gregorio decided to quit.

Nevertheless, Benito suggested otherwise and proposed to give him part of his land, where he would commission the construction of an Italian pasta restaurant, in recognition of all the years that he had worked for him. Benito, during all those years of shared work and friendship, had taught José Gregorio how to cook his homeland’s recipes. José Gregorio accepted and they came up with the idea for what they called La Cantinela de la Pasta.

They did not have many customers at the beginning because everything seemed to have come to a standstill due to the gasoline shortage.

Journalist Yover Vásquez, who worked at Trujillo’s 102.5 FM radio station, spread the word about the hitherto unknown restaurant over the air. From that moment on, people began to visit the place and the restaurant gained a good reputation.

Clients would treat themselves to pasta with Bolognese, Marinara, Napoletana, or Carbonara sauces, and to the house specialty: the Cantinela Ragu sauce, with lamb, pork, and beef, crowned with pesto.

Later on, already in their teens, Cristian and Gregory helped to dish up the food and carry it to the tables. They also learned to set the silverware, serve the beers, and leave the glassware squeaky clean.

José Gregorio continued working on La Rumorosa and in the restaurant simultaneously for ten more years. In 2012, he and his wife decided to commit themselves fully to the pasta business, and Benito sympathized.

Things were going smoothly until 2017, when it all got more and more complicated because of the economic crisis that Venezuela was going through. Two of the three restaurants that operated in Sabanetas closed their doors. La Cantinela de la Pasta had found a way to survive, until the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

At one point, with the country in quarantine, the gasoline shortage, and having sold not a single pasta serving in weeks, José Gregorio thought it was the end and that he would never again seduce people with his kitchen’s aromas.

“We are going to starve to death,” said José Gregorio to his wife.

She did not utter a word.

That’s when Cristian proposed an alternative.

“You know what, Dad? Go ahead and make the sauces. I will sell them in Trujillo.”

It didn’t strike José Gregorio as a bad idea, so he started cooking again. The first vapors of the onions, as they made contact with the hot oil, cleaned the heavy atmosphere that had taken over the house. Consuelo smiled as she felt her kitchen come back to life.

Cristian made a list of potential clients. He planned to make the route by foot because he was well aware of the issues with public transportation. This time, when he went down to the city, he sold five jars. Then he had Gregory join him. And they devised a routine that brought a sense of excitement back into their house.

It is October of 2020, and the two brothers have just arrived from work. They are hungry but happy. They know that theirs is a temporary solution to keep the family business afloat.

Sigue La Ruta del Hambre en: Sé que esto que estoy atravesando no será eterno

This story is part of La Ruta del Hambre [The Hunger Route], a publishing project developed by our network of storytellers in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

This story is part of La Ruta del Hambre [The Hunger Route], a publishing project developed by our network of storytellers in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

3664 readings

I was born in Valencia, Venezuela, on May 25, 1993, but I have been living in Trujillo since I was nine. I am a professor of communication and media at the University of the Andes, Rafael Rangel Campus. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].