After Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état against Salvador Allende, many families migrated from Chile. It was the case of the Ponsots, the Balaguers and the Escobars, who lived in Finland for some time and then settled in Venezuela. Decades later, some of them went back to the point of departure.

After Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état against Salvador Allende, many families migrated from Chile. It was the case of the Ponsots, the Balaguers and the Escobars, who lived in Finland for some time and then settled in Venezuela. Decades later, some of them went back to the point of departure.

A floor cleaning cloth was the first thing Loly came across when she opened the black suitcase that her mother had been putting together for two years for when she returned to Chile with her.

Two days before Loly decided to rummage through that piece of luggage as if she were defiling a treasure, Marina Balaguer, her mother, died of septicemia in Mérida, at the end of the white mountain range that connects Venezuela and Chile. She was 63. It was December 1998.

Loly, who was born in Chile but was raised in Venezuela and became a Venezuelan national through naturalization, guesses her mother had packed the floor cloth to show Chileans how they are made like in Venezuela, for no doubt it was different from the ones they used in Chile in 1973, back when the family was forced to flee from the military forces of Augusto Pinochet.

Whit her mother’s death, the plans to return to her native Chile were suspended. Loly would continue living in Venezuela.

Loly laughed and dabbed away the tears that kept falling from the two round, blue dots that were her eyes, hidden behind her magenta glasses, as she discovered the most bizarre things coming out of that suitcase: a collection of antique irons that weighed about eleven pounds, almost a quarter of the airline’s weight allowance per passenger. Ernesto Ponsot, Loly’s father, who had separated from Marina Balaguer a couple of years earlier and had moved to the room across hers, had been looking for months for his relics to decorate his new space. It could be that she never stopped loving him and she just meant it as a prank.

Marina Balaguer was born in Spain, bur she was raised in Chile and became a Chilean national through naturalization. The Spanish Civil War forced her family to leave their country. She was only 4 years old. The SS Winnipeg set sail on August 4, 1939 in the port of Pauillac, France, 622 miles or so from Marina’s hometown, to Chile. It was a 100-passenger ship, but the poet Pablo Neruda, who had performed as consul of Chile in Spain, arranged for it to accommodate more than 2,000 refugees, including Marina, her brother Tomás, and her parents Tomás Balaguer and Dolores Quílez. Their youngest daughter, Choni, would be born in Chile years later.

Tomás Balaguer senior, who was not that old at the time, was a construction foreman. He was also a professional referee for the First Division of the Spanish Soccer League, and from 1930 to 1936 he refereed thirty-one matches for the division and a number of matches for the King’s Cup.

He was a nice man with a strong personality, and he was so overly macho that he refused to use deodorant because wearing perfume was a “whore’s thing”, as he put it. He still pronounced “s” as “th” because he never lost his native accent despite having lived half his life outside Spain.

The ship, and its human cargo of doubts, dreams, and hopes, crossed the Atlantic Ocean and the Panama Canal, skirted the Pacific coast, and arrived at its port of destination a month later.

The hydrangeas flirted with the sun and the poplars swayed in the spring wind along the occasional kite, soaring high, reaching for the sky. Such is usually the weather on the eve of September 18, when the people of Chile celebrate their Fiestas Patrias.

There are times when an extremely painful event becomes an anchoring point for the hopes of others. Don Tomás Balaguer found a better future among the rubble from the Chillán 8.2 earthquake that had hit Chileans nine months before. With a death toll of around 30,000 people in a population of 50,000, it is the deadliest earthquake in Chile and the third deadliest in the world. Don Tomás was one of the construction craftsmen who helped the city rise from the debris with bricks, iron bars, and hard work.

Loly’s eyes sparkle bluer when she talks about her grandfather “El Tata”, as they called him when the saggy skin under his eyes had stretched down to his sweet wrinkled cheeks and his bowed legs made him swing from side to side, dragging his house slippers.

He enjoyed spoiling her and made her garlic bread and also a delicious gazpacho, like a true Spaniard. They would occasionally dance to the tune of a pasodoble. She was the apple of his eyes. And rightly so, because Loly was his only granddaughter: his other grandchildren were boys.

Don Tomás and his family lived in Chile for many years. Little Marina turned into a woman and, as soon as she finished high school, headed to Santiago to pursue studies in education, and then in mathematics. Once she was awarded her university degree, she went on to become the head of the Institute of Statistics at the University of Chile.

That is where she met Ernesto Ponsot.

He was a postgraduate student. They dated —or Pololearon, as Chileans say— for six months and got married without giving it a second thought.

They had Ernestito, the red-haired one, aka Tito; then, Tomasito, forever El Chico; and on November 3, 1971, Marina Dolores, the blue-eyed, light-brown skinned girl who is the main character of this story, also known as Loly in the family.

The day she was born was the first-year of Salvador Allende’s term as president of Chile. Marina and Ernesto were active members of the Socialist Party, an organized group that, along with the Communist Party and other political movements, had brought Allende to La Moneda Palace.

It would not take long for changes to be implemented: Allende nationalized copper, froze prices, rose salaries; in a nutshell, he undertook a series of measures that led to citizen polarization, at a time when people had begun to make long lines just to purchase basic goods.

Loly was too young and she does not remember, but a few decades later she would have to live through a similar experience.

On September 11, 1973, Augusto Pinochet staged a coup d’état and Allende ended up dead in La Moneda.

After that gunshot, the lives of Loly and her family took an unexpected turn. A witch hunt was unleashed that triggered a wave of persecutions, torture, detentions, and executions by firing squads. The military forcibly disappeared detainees by dropping them into the sea from an aircraft, throwing them down a cliff, or burying them in mass graves where they would be engulfed in dirt for good.

That could have been the fate of the Ponsots had they not moved fast.

The troops did not waste any time and went after them. Staying in Chile was out of the question. They had to leave. Ernesto was the comptroller of El Teniente [The Lieutenant], the longest underground mine in the world, and, since the mine was run by the Chilean State, no stone was left unturned to find them. Ernesto was arrested, beaten, and taken to a firing line where he lived the most terrifying experience in a mock firing squad.

He pulled some strings and got out, and with the help of diplomats such as Tapani Brotherus, who performed as the consul of Finland in Chile at the time, he found refuge for him and his family.

From that moment on, his luck would be like a spinning ball on the roulette wheel of life.

Persecuted people fled the country in droves however they could. The Ponsots left on a plane that made stops in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Lisbon, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Stockholm and landed thirty hours later in Helsinki, the capital of Finland. This chapter of their story made it into a Finnish Netflix series called Invisible Heroes.

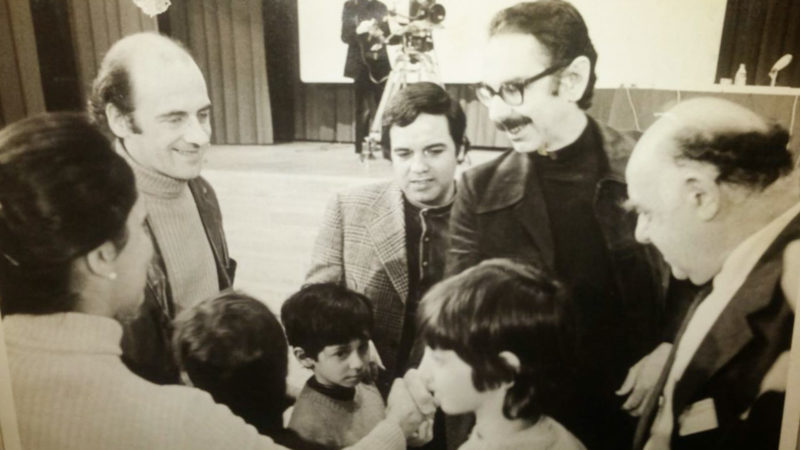

Which they lived alongside the Balaguers, the Escobars, the Veras and the Leppes. They each had two or three children who enjoyed the trip as if they were going to Disney World. Photos of their boarding and leaving the plane were published on the front pages of some Chilean and Finnish newspapers.

Those press clippings, turned yellow with the passage of time and the brunt of so many stories and struggles, have travelled in many a suitcase and are part of one of the treasures that Loly holds the dearest to her heart, which she posts in her WhatsApp statuses, intent as she is to keeping the family legacy alive.

The temperature in Chile was 30° C when they left. It was -30° C when they arrived in Helsinki.

The women, in full mourning, as they felt they had been dragged out of their homeland, were greeted with flowers, and the children were presented with a gray teddy bear almost their size.

Loly still keeps hers.

They lived there for of twenty months. Sure, they were accorded a fraternal reception by the Finns and, for that, they are forever grateful, but they found it difficult to adapt. The weather there is invariably cold except for a couple of months during the year. When the sun peeks out, the pine forests —where mushrooms, berries and squirrels abound— catch the rays. The Finnish language was hard for them to learn, although some eventually did. At the age of two, Loly’s Finish vocabulary included some basic phrases that got her through life, such as “Hello, how are you?”, and a few swear words that one would rather not repeat, lest a Finnish reader should happen to read these lines.

Don Tomás was one of those who had the most difficulty learning Finnish. He was 74 years old. But that would not stop him from running errands, and he always found a way to make himself understood. One day, he mimed to a cashier at the supermarket: he grabbed a piece of cheese with his right hand and placed his left hand against his chest, as if it were a grater, moving the cheese up and down. The cashier, convinced that she had figured out what he wanted, brought him a cheese grater. He did not give up, though. He mimed again, more energetically so, cupping his hand quickly to “catch” the grated cheese. Exactly. That was what he wanted. He came home with his grated cheese and a story to tell.

They decided to migrate again.

The first two times her family had had to go into exile, they had left in a hurry and at gunpoint. This time around, things were different. Ernesto had a job, they lived modestly but comfortably, and they had access to healthcare, education, and security. However, they longed for something like that which they had been forced to leave behind. It was impossible for them to go back to Chile. Even Loly and the other migrant children had been forbidden entry thereto by the dictatorship laws. And Pinochet was still in power.

It is 1975. Venezuela, with its bold, generous sun and its oil boom, was an attractive country. It was also Carlos Andrés Pérez’s first term in office and he had opened the country’s doors to migrants.

The Ponsots, the Balaguers and the Escobars left together with the same destination. The Leppes and Veras stayed in Finland.

Ernesto Ponsot and Marina Balaguer and their offspring settled in Mérida, in the Venezuelan Andes.

Loly’s room had a view of the farthest peak of the Andean mountain range, the one that starts in Chile. When they went on vacation, they used to hang out with Escobars, who had moved to a city far away from theirs. Life had brought them together and, in their eyes, they were family.

Eleven years later, when Loly was 14, Don Tomás took a one-way trip to Chile, as if he wanted to reunite with his beloved Dolores, whom he had widowed years before they left for Finland.

Beginning in 1994, when Loly was 23, a series of events unfolded that would mark her life. She got married. She got a divorce. In 1998, she was awarded an architecture degree. Then, five days later after such a joyful accomplishment, life dealt her the bluntest of blows: her mother died.

That Christmas afternoon, Loly finished unpacking her mother’s suitcase and shelved her plans to leave for Chile.

She traveled half of Venezuela looking for a job as an architect. She established a successful company in El Tigre that provided services to the oil industry. The company might have been fate, again, taking her to that rainy city in the state of Anzoátegui to conceive the most wonderful human being in her life, the one who made her eyes shine bluer, the recipient of her love, her drive to fight new battles: Eduardo, whom she gave her two family names: Ponsot Balaguer.

The government’s demolition machine was already in motion and was starting to wreak havoc on the country. The company went bankrupt and Loly had to pack again, this time to Valencia, Carabobo, where she worked in ergonomics designing work stations and work processes to protect the health of workers.

However, life was getting harder and harder and, from what she had learned from her elders, she just knew that the crisis was just beginning. That is when her plans to move to Chile began to take hold again, 16 years after her mother’s death.

And the day came and history had found a way of repeating itself. On October 1, 2014, at the age of 42, Loly returned to her birth country, not with her mother, but with her 9-year-old son.

She planned to pursue a master’s degree in ergonomics, and she did. She just wishes her father, who was into the academic world, could bear witness to her achievement. He now rests in peace with her beloved Marina in Mérida.

She fought hard to make a name for herself in the field in Chile, to no avail, so she ended up giving up on the idea. Now, in yet another twist of fate, she reunited with Ximena Escobar, the girl with whom she played with teddy bears in Finland, who is a journalist. Ximena too had chosen to return to Chile, but a year later. She settled and opened a small store. They both work behind the counter and, from time to time, they relive their shared stories. These lines are a testament thereto.

In between memories, Loly tends to the customers, making a conscious effort not to confuse the names of the many things that are called different in Chile. When she lived in Venezuela, she spoke with a bit of a Chilean accent that kept her grounded to her roots. Now, in Chile, she is more Venezuelan than ever. She misses the people, the empathy, the smiling and the spontaneous greeting. She would love to go back, but she quickly does the math and, in her opinion, it will take many years for Venezuela to recover, and her guess is that she won’t be there to see it because of her age. But Eduardo is what really keeps her where she is. He, a tall, dark-skinned, slim young man with brown eyes, full lips, and curly hair —her complete opposite physically—, is already losing his Venezuelan accent, and Loly doesn’t want history to repeat itself.

The time has come to put the bags away. Perhaps they will go back on vacation one day. For the time being, she is ready to use her Spanish DNA to her advantage and has decided to process her Spanish passport, just in case.

This story is one of the many written within the framework of the Tras los rastros de una historia [Trailing Stories] workshop that we offered to fifteen Venezuelan migrant journalists through our online El Aula e-nos platform in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

This story is one of the many written within the framework of the Tras los rastros de una historia [Trailing Stories] workshop that we offered to fifteen Venezuelan migrant journalists through our online El Aula e-nos platform in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

1352 readings

I am one of those journalists that edits even the hashtags. What is the purpose of life if not to tell stories? That’s why I created the Dicho y Hecho journal, which ran for 16 years. And I am still standing and telling stories.