Ten months after having migrated to Perú, she received the news that the woman who raised her had died in Caracas. From that moment on, she has made sure that her grandparents, who have had to overcome the hurdles imposed by an ever-worsening economic crisis, are doing well. At night, Pierina Sora prays to God that she will soon be reunited with them.

Translated by Yazmine Livinalli

“May God bless you, keep you and be with you. Have a nice day, mija.”

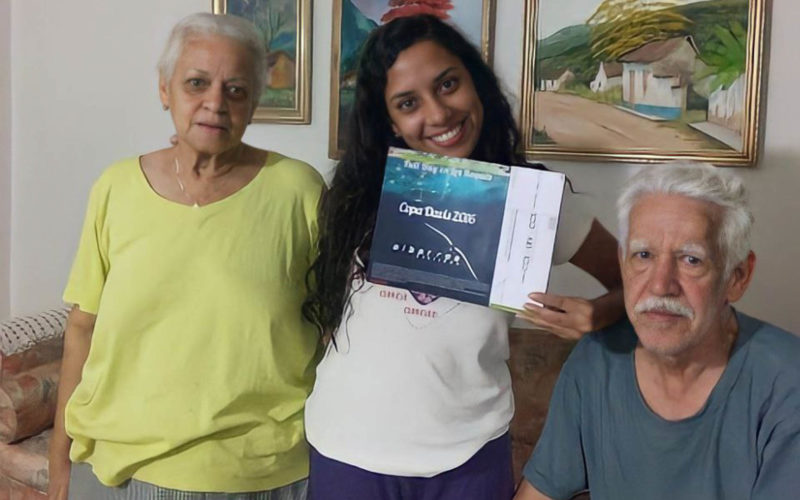

My grandparents, Julio and Encarnación, will not start the day without sending me a voice note to say hi. They live in Catia, in western Caracas, and I live in Lima, Perú. For them, time seems to pass at a slower pace. They can’t go out shopping nor visit their relatives. They don’t have a car and, as they tell me, a taxi fare may be up to fifteen dollars, an amount they would rather spend on food.

My grandmother gets up at daybreak, fixes breakfast, and tidies or cleans the house. Next, she makes lunch. In the meantime, my grandfather is at work. He didn’t have the opportunity to go to school because, when he moved to Venezuela from his native Spain, he had to help his father to support the family. Along the way, though, he happened to discover the carpentry trade, which he has never abandoned. He still works every day in his carpentry shop and is always looking for something at home that needs to be repaired or renovated, and sets right about it.

“It’s the only way I have found not to stay in bed all day and not to think so much about stuff,” he says.

Sanding, gluing, varnishing. That’s how he spends his days. Although he doesn’t do as many things as he used to — both because of the rising cost of materials and because, at 78, time has taken a toll on him —, he makes chairs and helps his neighbors repair their wooden items. He is not one to charge for that. Sometimes he is paid in kind, be it food or fruit. And he is always grateful.

My grandparents have also found another hobby: they love home gardening. In their house’s yard, there are pots where they grow bell peppers, chives, garlic, and basil plants. Every now and then, they send me photos of their harvest.

In the afternoons, they take a nap, after which they have a cup of coffee or tea with a visiting neighbor or relative.

I feel reassured to know they are all right, for it has not been easy to have them so far away. We have had to go through many an ordeal from afar.

My grandmother is into voice notes. She always sends them to me, telling me how she is doing, what she is doing.

“Today has been a good day. We’ve already eaten. Your Nonno is watching TV and I’m cleaning up some things in the kitchen.”

She also sends me love stickers.

My grandmother is 72. When she noticed that her neighbors in the building knew how to use WhatsApp to communicate with their children abroad, she promised me that she would learn how to use it to talk to me.

“You’ll see. I will learn how to use it a flash, and I will save money to buy a cell phone.”

She made that promise one day in 2020. I vowed that I would buy her that cell phone, which I kept to myself because I wanted it to be a surprise.

On May 9, 2021, which was Mother’s Day in Venezuela, she received a parcel.

“Thank you, my dear princess! I am ecstatic! Now we will be able to chat! I will learn how to use it.”

And learn she did, through neighbors and relatives. It only took her a few months.

Her first note read:

“No matter the distance that keeps us apart, our family’s love and heart brings us closer together.”

So now my grandmother sends me stickers, audios, videos. That’s how I feel her and Grandpa close to me. They are my most precious possession.

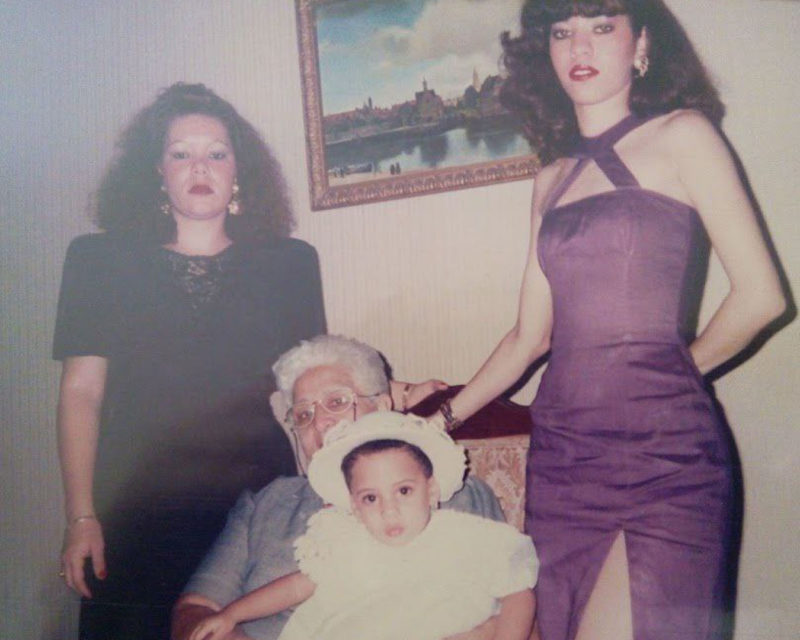

I was born in Guatire, a sultry weather city in the state of Miranda. When I was a 3-month old baby, I was taken to Catia, west of Caracas, to the home of my uncle Julio and my aunt Encarnación. He was 47 and she was 41. They would soon become my grandparents. They were the ones who raised me.

When my mom got pregnant, my father told her that he already had a family to look after. She was dealt the abandoned single-mother card. When she gave birth to me, my maternal grandfather was in the hospital with diabetes. My mom had no job and had to take care of him. She didn’t know what to do. Tending to a little baby and to an adult in poor health at the same time was an overwhelming task. In light of the situation, my grandfather suggested that she take me to Encarnación’s, my maternal grandmother’s sister. The family had been very supportive of my mother during her pregnancy, which is why he knew that they would take good care of me. And so they did. My grandparents had children, but none of them had children of their own, which means that they had no grandchildren. Until I came along and they decided that I would be theirs. I am their only grandchild, ‘La Piera’, as they like to call me. Ever since I was a little girl, I call Julio Nonno and Encarnación aunt. But I have never told my acquaintances or friends that they are actually my uncle and aunt: I have always introduced them as my grandparents. Besides, in the absence of my father, Julio has been an important male figure in my life.

When I arrived at their place, there was Jamilet, Julio and Encarnación’s daughter. She was 16. Little did she know that, at such a young age, she would have to help raise a girl. She would get up at 2:00 a.m. to feed me a bottle of milk. She would take me to school and help me with my homework. Everyone at home contributed in a way to my upbringing. We were not your traditional family, but everyone took me as their own.

I remember 2016 as one of the most difficult years for us all. As a family, we lived on a tight budget and could not afford the luxury of going on trips, eating out, or buying a car. But we never ever lacked food… until the economic crisis took a seat on our table. In 2016, we could not pay for a basic shopping list of proteins, grains, vegetables and personal hygiene products. Not even if we put together my two salaries, my foster mom’s salary as a preschool teacher, and my grandparents’ pensions. Inflation was rampant, shortages were taxing, and the long lines one had to make to buy things were grueling.

That year, after several hours in line under the scorching sun just to buy toilet paper, I collapsed on the asphalt.

“That’s it. You won’t stand in line anymore, much less if it’s to buy stuff to wipe your ass!” my Nonno told me, authoritatively, when I got home and recounted what had happened to me.

We were not eating a good diet. For months, we survived on soup mix packets and on the tiny loaves of bread we could buy for a reasonable price at a local bakery. A small bowl of soup and one and a half pieces of bread per head: that’s all we could have. We knew that was not enough for anybody, but at least we had something to keep us going through the day.

I felt that I was incapable of helping my family and that my salary vanished at the same rate as the uncertainty about how the crisis in Venezuela was being handled increased.

It was then and there that I decided to leave my country, which I did with two goals in mind: to improve my quality of life and to help my loved ones. At 27, I wanted to grow as an individual. I wanted to experience firsthand how is life in a society without having to buy stuff by your ID terminal or have your fingerprint scanned by a machine to check if it is your turn to purchase a given product. I was worn out. I wanted to witness a different reality. I wanted to go out on the streets and not see entire families, with their children and teenagers in tow, rummaging through the garbage to put some food in their stomach.

I left home with my partner on January 22, 2018.

My grandparents got sad when I finally moved. My Nonno knew we wouldn’t see each other for a long time, but he also knew that it was in my best interest. That’s what he would tell me.

I guess it was easy for him to relate to my situation because his was a family of migrants too.

My maternal nonno, Antonio Sora, fled Italy and settled in Venezuela in 1958, just when the dictatorship of Perez Jimenez was falling. My other grandfather, Julio Ávila, who had been displaced by the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, was among the one hundred irregular Canary Islanders who crossed the Atlantic. Both Antonio and Julio suffered the cruelties of the European wars.

Julio was 9 years old when he set foot in the Caribbean with his parents. The ship in which he made the crossing arrived at the port of La Guaira in 1952. His memories of the time when he fled his country are somehow blurred. “The trip must have taken between fifteen days and one month. I was seasick the whole time. The people who didn’t have relatives waiting for them at the port had a terrible time and had to sleep for two days in Plaza Bolivar,” he once told me.

I grew up as the granddaughter of migrants.

Now I am a migrant myself.

My grandfather’s words were no longer foreign to me.

It took me six days to get to Perú by road. On my way there, I saw countless Venezuelans for whom the journey was just hell on earth. They had nothing to eat. They could barely pay for their tickets.

My partner and I were lucky. We found a job a few days after we arrived in Lima, so we were able to set aside one hundred and fifty soles, which is the equivalent of fifty dollars, to send to our relatives back in Venezuela. For them, it was a lifeline in the middle of the storm.

That was until 2017, when hyperinflation hit hard and remittances ended up being worth next to nothing. What we were sending was not enough. We started to worry. We could tell from a distance that life in Venezuela was increasingly difficult for our people. And then came the blackouts. People went without electric power for days and nights at a stretch.

In October 2019, maybe due to fluctuations in power, the motor of my grandparents’ refrigerator stopped working. They didn’t say a word to me because they didn’t want me to worry. I have always maintained that those who stayed in Venezuela and those who, like us, live abroad are tacitly silent when it comes to sharing our things: we do not tell much to avoid causing further distress to those on the other side.

I learned about the refrigerator through a relative who lives by my grandparents’ house. I had no steady job, so whatever I earned I used to pay my rent and the utility bills and buy food. It was in no position to send enough money for the repair.

And then the pandemic broke out. There were lockdowns everywhere. The situation got even direr for me.

Additionally, my grandparents were being subjected to water shortages. During one of our phone calls, they told me that some neighbors had brought them drinking water. They didn’t even have drinking water. It broke my heart to pieces. I felt powerless that I could not do more.

“They need to keep their vegetables and their fruits refrigerated. How can they be without a fridge? What kind of a life is that?” I thought. I felt miserable but, perhaps not to sit idly by, I began to check prices: a brand new motor was between seventy and one hundred dollars.

It is not an easy amount to secure. My grandparents sold some of their household items at prices as cheap as chips and began saving little by little. Some relatives gave them food and money. Any contribution, be it one, two or five dollars, was a blessing.

In July 2020, I took it upon myself to find a store to buy it.

“It’s seventy dollars, and it comes with a one-year warranty,” the saleswoman told me via WhatsApp.

My grandparents had managed to collect thirty-five. I sent them the rest. My uncle and a cousin went to the store and bought it. I also sent money for a technician to install it.

After eight months, my grandparents would have a working refrigerator again.

I was relieved.

But that was not remotely the worst experience I have had since I left them back there.

Ten months after arriving in Perú, I received the soul-crushing news that my foster mother had passed away. It all happened so fast. On November 21, 2018, she woke up with chest congestion, trouble breathing, and extremely frail. My grandparents and my uncle called a relative who owned a car. They took her to two different hospitals, but she wasn’t admitted. When they got to the Periférico de Catia, she had no vital signs. The doctor who checked her said that she died of respiratory arrest. We couldn’t know for sure what had happened because there was no autopsy. But that is another story. A story that I will tell at some point.

I had to mourn a loss while far from home. I had to pull myself together to provide my grandparents with comfort. It was a major blow to them. A family of five had been reduced to three.

My grandmother tells me that, even if things are not the same, we will always be united. There is a small wooden table in one corner of the living room where photos of me are displayed; on the other side of the room, there is a small home altar with photos of my mom, flowers, a glass of water and, every now and then, a candle by the little box that holds her ashes. It’s been almost three years now and they have not had the courage to part with them. Perhaps during my next visit we will perform a farewell ceremony together.

Finally, after three years, I am formally employed. Although what I earn is not enough to fully support my grandparents, I still do my best to take care of the smallest things. After my mother passed away, I took on certain responsibilities such as making their shopping lists, checking prices, calling grocery delivery services and making sure the products arrive.

I am immensely relieved when they receive their purchases. I know Venezuela is no country for old people, much like in the No Country for Old Men movie. Old people who cannot work or who do not get help from relatives abroad to buy food or for emergencies have a really hard time.

In 2018, I was sending them twenty dollars a month. Today, that amount is good for almost nothing.

I know that Venezuela is different now from the country it was when I left. The long lines are a thing of the past. From what I read and from what I am told, shelves in supermarkets and delicatessen stores are fully stocked. Everything is imported and priced in US dollars. My family cannot go to there to buy food and other necessary supplies.

From time to time, and on special dates, I have desserts and fruits sent to them that I know they cannot buy. That’s how I spoil them. On birthdays, my grandmother bakes a cake. She takes her cellphone and makes a video call, while she arranges pictures on the table, to make us feel closer. My family and I know that we owe each other many hugs. We also know that we need to mourn and grieve our loss together. And celebrate my accomplishments.

I hope that soon we will be able to honor that debt.

At the beginning of 2022, I finally completed the two hundred dollars that I needed to apply for a new passport, for mine expired. I also set up a savings plan to go to Venezuela. It is not cheap. Tickets from Lima cost around seven hundred dollars. My salary is one thousand two hundred soles, or about three hundred and twenty dollars. Sometimes I fret because I feel it is extremely difficult for me to go back to my country.

But I can only think of the moment when I will open the door and I can finally hug and look at my grandparents. We are fed up with the hugs, smiles and tears through a screen. I want them to greet me with the same love I felt the first time I came home. I want to be filled with love by them. I want to shower them with my love. I want to make them the Peruvian cuisine recipes I have learned. I want so many things by their side…

I believe in the power of prayer. Every night, when I go to bed, I ask God to protect them and to grant us the desire that we meet again.

Esta historia fue desarrollada en el taller “Comenzar a contar(Nos)”, impartido por nuestro editor senior Erick Lezama, a través de la plataforma El Aula e-nos, en el 4to año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

1319 readings

Until a few years ago, I was physically and emotionally the granddaughter of migrants. Now I am a migrant myself. So I put a lot of effort into creating content to better understand the subject.