On May 18, 2017, a National Guard officer fired a tear gas bomb at point-blank range at the body of Oscar Navarrete. He was taken to a clinic showing no vital signs on admission, but he responded after the fourth resuscitation attempt. The doctors predicted that he would be left in a vegetative state, but Carmen, his mother, refused to accept the diagnosis. Today, from her hand, Oscar is learning to live again.

Photographer: Valeria Pedicini

Photographer: Valeria Pedicini

All of her life Carmen has woken up with the first gleams of the morning light. She has always thought that 5:00 am or 6:00 am is a good time to stretch and peel the sheets off of her body. That morning was no exception to the rule. Whether she wanted it or not, the rays of light were piercing her eyelids. The sun, which worked as her alarm clock, filtered through the curtainless windows of the hospital room. She would take turns with both her eldest daughter and the nurse to lie on the room’s second bed or on the floor mattress. She had forgotten what it was like to sleep for more than four hours straight.

It had been weeks now since Oscar, her other son, had been staring everywhere and nowhere at all from the room’s main bed. He had lost all intention, which was hidden somewhere in his unconscious. He could stare at a single point for several minutes at a time, his eyes fixed, almost without blinking, as if he were paying attention to something of which the rest of the people remained oblivious. Maybe it was a crack in the ceiling. Maybe he was recalling the events of May 18, 2017. He didn’t move, he didn’t react to stimuli.

Mother and son had agreed to use the only form of communication they had left, which they learned during the hours they had spent watching movies: the blinking of the eyes. Closing the eyes for several seconds meant yes. Over-opening them, almost disproportionately, meant no. This is how it had been for 40 days since the young boy was sentenced to live in a vegetative state. That was the diagnosis. For him, they said, there was nothing left to do.

His mother would talk to him anyway. She kept trying to have some sort of a conversation, which would end up in a monologue.

—God bless you, son of mine. How did you wake up today? —. There was no answer back for Carmen, but that didn’t stop her from trying again the next day, and the next, and the next day, again.

Was it July or August? Carmen doesn’t remember exactly. She no longer looked at the calendar. She had had little rest because she spent her nights more awake than asleep, watching over her son. At 5:00 am she had already taken a shower and was making breakfast on the small electric stove that they had plugged into the bathroom switch. At 9:00 am, like every day, the three of them were sponge-bathing Oscar in his bed. They would move him carefully, undress him, clean him, and dress him up again.

Carmen was by his side, covering him with fresh clothes.

And then Oscar looked at her.

Not exaggeratedly, not as a reflex of his eyelids. He looked at her deliberately. He looked for her with his eyes. He looked directly at her.

It was just for a few seconds, brief as lightning, but Carmen was shaken.

—Oscar looked at me! Oscar is looking at me! —, she said to her daughter and the nurse.

Neither of them believed her.

—I know that you can hear me, my son— she now told Oscar.

She felt tears running down her face. She cried. She smiled. She was overflowing with joy. She leaned over her son’s body and pressed it lightly against hers. After several weeks, she finally felt what she had been forcing herself to have: hope. Yes, it was the first time they had looked at each other. Yes, her son was born again.

But birth is only the beginning of the road.

Oscar Navarrete was first born when he emerged from her mother’s womb. It was 2000. He is the middle child, sort of the filling in the sandwich. He is younger than Genesis for three years and older than Leonardo for just one.

Fate challenged him very soon and at different times. The first time, his mother was barely five months pregnant with him. It was early on a December morning when rain poured down from the sky, as if it were crying grief and despair, and the earth roared, and the mountains slid over the houses of Vargas. But in Caraballeda, Carmen and her unnamed baby came out unharmed.

Fate: 0, Oscar: 1.

Seven months into her pregnancy, a cyst would strangle one of Carmen’s ovaries. She would need to undergo a high-risk operation. If it got complicated, she was told, they would have to take the baby out. She entered the operating room in fear but it all turned out well.

Fate: 0, Oscar: 2.

According to the calendar, Carmen was already into the eighth month of a happy pregnancy when she had peritonitis, which is said to be a deadly infection. Once again, everything went well.

Faith: 0, Oscar: 3.

And Oscar scored yet another point when, at nine months, just as scheduled, an incision in her mother’s abdominal and uterine wall brought him to life.

Fate: 0, Oscar: 4.

On May 18, 2017, though, faith sought him out for revenge.

Protests against Nicolás Maduro had been going on for 48 days. Those were days of marches, road blocks, strikes and repression. Huge repression. From the very beginning, Oscar answered the calls and went out to the streets to demonstrate. Sometimes he would go with the family, sometimes with classmates, sometimes all by himself. Ironically, that day’s rally had been summoned to protest against repression by the State’s security forces. And he got to live the repression up close and personally.

His mother was in Puerto La Cruz, where she officially lived with her children, except Oscar. She had him move in with his grandparents in Guarenas so that he could be closer to the city, finish his last year of high school and have access to more opportunities. But the opportunities were not necessarily the best.

Facebook launched a notification.

—Hey, Carmen. Do you know this young man that you have added to your Facebook account?

—Yes, he is my son.

—They’re looking for his relatives, he has been wounded.

Her mind got clouded. Her son? Oscar, wounded? It couldn’t possibly be. She didn’t know what was going on. Was he actually wounded? What if they didn’t want to tell her the truth? No one would give her accurate information.

She thought of everything: torture, detention, death. Social media images of young people wounded replayed in her head at full speed. She would have snapped her fingers and leaped the distance if she could, but that day there were problems with public transportation and she wouldn’t have been able to get to Caracas by bus. She would need to wait until the next morning, but no bus was leaving until 9:00 am or 10:00 am. It was that or nothing. She had no choice but to wait. That night she couldn’t close her eyes.

Oscar doesn’t remember many things; two years of his life have been lost in his memory. Every 10 minutes he forgets something. If he sees someone today, he doesn’t remember tomorrow. At lunchtime he can’t remember what he ate for breakfast. He doesn’t remember having moved to Caracas or that he was studying his last year of high school and was about to graduate. He doesn’t remember anything beyond Anzoátegui, beyond his 4th year at school. A cerebral edema has taken his memories hostage. Two years of his life were erased from his mind in a single shock. From a single blow.

People say that Oscar was in Altamira, as he used to in so many other days of protest. That day too, the script was followed to the letter: first march, then repression. He was in the company of some friends, already on their way back from the demonstration, when they got intercepted in a street. An officer of the Bolivarian National Guard raised his gun, pointed it at Oscar and fired at a distance of less than 10 meters. He shot it at point-blank range. He shot to kill. The tear gas bomb hit him on the chest, on the left side. He was left in a state of shock and fell to the ground.

Oscar suffered cardiorespiratory arrest from the impact. Simply put, he had no vital signs. His heart stopped and his lungs collapsed. Oscar died.

Was anyone counting? Fate: 1, Oscar: 0.

The demonstrators at the site picked him up and put him on a motorcycle. His face was pale and his mouth was slightly open. One person sat behind him in an effort to keep him upright. Otherwise, the weight of his body would pull him sideways. That’s how they got to Clínica La Floresta.

Three resuscitation attempts, which is the number of times that doctors say they have as a reference to bring the dying to life, were not enough to make him breathe again. But they didn’t give up on him. 1, 2, 3… Finally, they got a response on the fourth attempt. Oscar had been with no vital signs for 40 minutes.

This time it was not Fate: 1, Oscar: 0; it was a tie. Carmen was alone in the ICU room a few days later when the doctor broke the news to her.

—Your son has been left in a vegetative state— he said, bluntly.

She didn’t utter a sound. It did appear to her, though, that the doctor had given her the news as if he was a street vendor selling stuff. Those life-changing words are in no way easy to assimilate.

The news kept her awake for days. She couldn’t stop crying. She didn’t know how to tell her family, her parents, her other children about it. She refused to accept the diagnosis.

—He will wake up—. Such was her mantra. She would repeat it to herself once and again, quietly. She would whenever she was optimistic, but especially when she felt overwhelmed. If Oscar’s foot moved, Carmen saw a sign, even if the doctors saw merely involuntary movements.

Oscar spent 15 days in the intensive care unit. Two days after he was switched rooms, he experienced a second cardiac arrest. His heart stopped, again. For 25 minutes he had no vital signs, again. The doctors suggested that he should be disconnected. Carmen refused. It was out of the question. And it was her stubbornness that saved her son’s life. For her, a believer as she was, if God had given her son another chance to live, it was for a purpose. Growing up, it never crossed Carmen’s mind that she would have to endure tragedy. But there she was, accepting the life that she had been dealt without anyone asking.

Yes. On July 12th, Oscar Navarrete was born again. And then he had to grow up.

Carmen does not leave her son’s side. It was for him that she left her house in Puerto La Cruz and moved to a hospital room for several months. There she would sleep in a small bed or in the floor mattress. There were times when she couldn’t even fall sleep. Then one night, out of the blue, they got a call from the director of the healthcare center in Caracas that had accommodated them for over a year. They were instructed to gather their belongings and leave the facilities, without further explanation. They have since been living like nomads between their home in Puerto La Cruz, almost alienated from civilization, and Guarenas, crammed in a small house with other relatives, provided that they have the money to cover travel and other expenses. They only go to the capital city for the occasional medical consultation because the daily rehabilitation sessions are now over. They are now on their own.

She also quit her job as a substitute teacher to dedicate herself to Oscar’s care. Priorities changed over time. Now she has someone else to teach.

Oscar is learning how to walk. He takes short, shaky, fragile steps. Like a robot whose batteries are about to die out. He holds his mother’s hands tightly to maintain balance. He’s afraid to fall.

Oscar is learning how to speak. He began with desperate moans, trying to blow phrases through his tracheostomy tube. He couldn’t. He had to armor himself with patience, as had his mother. He has managed to utter more words with time, words that are short and almost imperceptible because of the faint volume of his voice. He releases a soft ‘well’ when asked how he is doing. His first word? They don’t remember. His mother wishes that it was ‘Mom’.

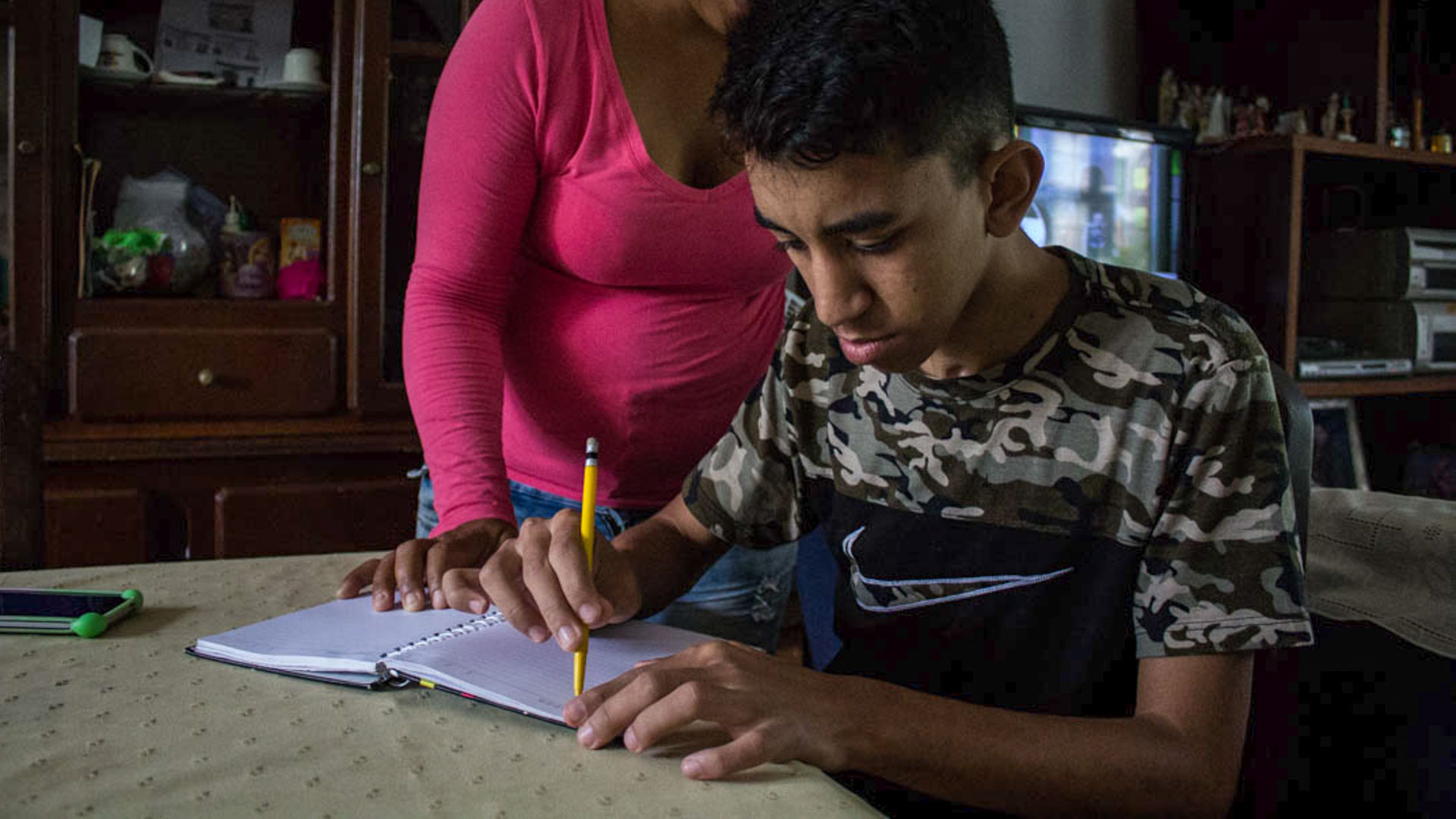

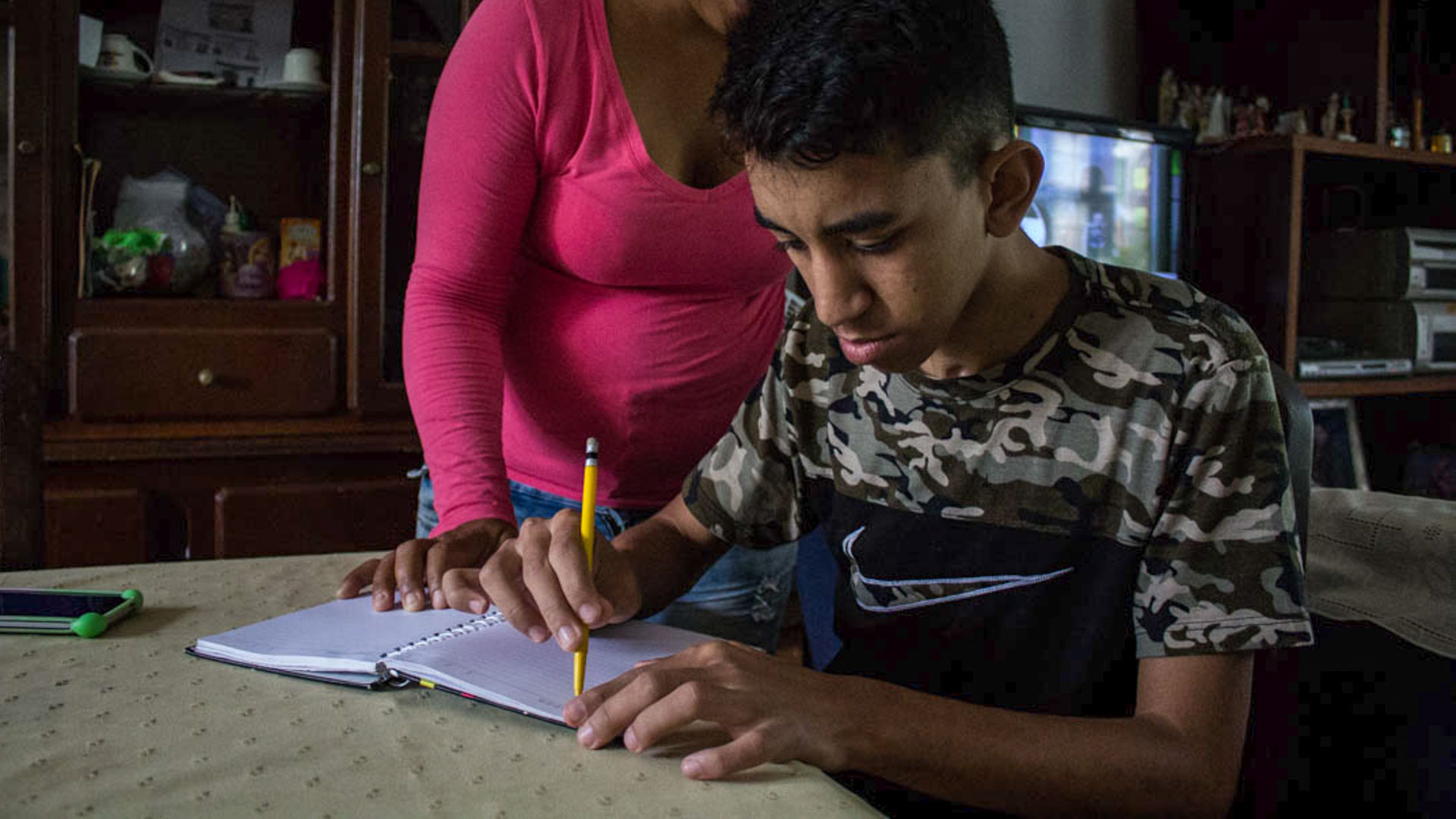

Oscar’s learning how to write. He can barely grab a pencil. His hands don’t remember how he held it between his fingers just months ago. What he does is to draw circles, or at least he tries to. Carmen tries with him. They haven’t succeeded at finding specialists that could help him. Little by little, he slowly manages to write five uneven letters so as to not forget who he is: Oscar.

Oscar is learning how to eat. The gastrostomy tube was his first assistant. Then it came Carmen’s turn to feed him with a small spoon. Now it’s his turn to grab the fork and slowly put it in his mouth. He has a strict diet and has to eat seven times a day. He has to take vitamins, proteins, calcium. The 44 or so pounds that he lost left him weak, like a skeleton, with his skin attached to his bones. Carmen sold her refrigerator and stove in an unsuccessful attempt at adding zeros to her bank account. Her partner sold his passenger van to raise money. It wasn’t enough. Neither for the food nor for the medicines that Oscar needs to take, which are quoted in US dollars. So, Oscar eats what he can and improves as much as he can.

Oscar is learning how to live.

On the last Mother’s day that Oscar spent with Carmen, he had no present to give her. He then promised that he would give her something that only he could buy.

—My present to you will be my high-school graduate diploma as soon as I get it.

—I know, sweetie. No need to worry.

The plan is on hold for now, as are the therapies that helped him to improve. His mother fears that instead of making progress, he will regress in his recovery. But Carmen is not giving up. Neither is he. Oscar is ahead in a game that is yet to be over, his desire to play unwavering.

Fate: 1, Oscar: 2.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was part of the work of Cigarrera Bigott’s “The Pulse and Soul of the Chronicle” XII Seminar of Narrative Journalism in 2018.

2580 readings

I am Venezuelan journalist with a degree from the Andrés Bello Catholic University. I hit the streets carrying a bag full of notepads, a great deal of curiosity and a desire to ask people questions. I am passionate about writing and photography, and I decided that that’s how I want to tell stories that move(me): through words and lots of camera clicks.