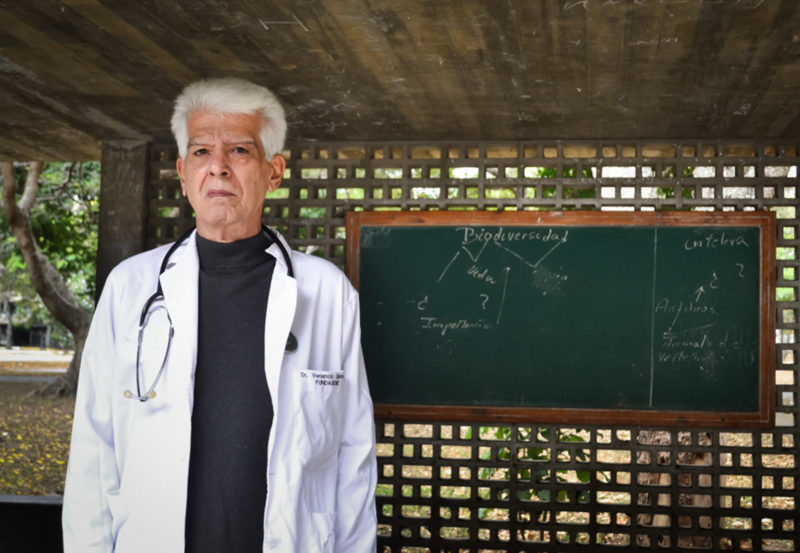

Medical geneticist Venancio Simosa has dedicated his life to studying rare diseases. The country’s crisis has left him without colleagues and students, and without patients who can come to his office. He has had no choice but to continue his work through remote consultations over the phone with other physicians. He is one of the few medical doctors remaining in Venezuela with a specialty that is, at present, as rare as the diseases it studies.

There was silence in the corridors of the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Central University of Venezuela, and the seats were almost empty. Doctors whispered so that their voices would not echo off the walls. It was a day in July 2018. Dr. Venancio Simosa already knew what was coming next, but he wanted to confirm it anyway. He left his office to check the bulletin board where the postgraduate chairs that would be taught the following year had been published. The slot with the classes he was supposed to be offering was empty. In 2019, there was no offer for human genetics, his specialty, for lack of pediatrics and pediatric dentistry students.

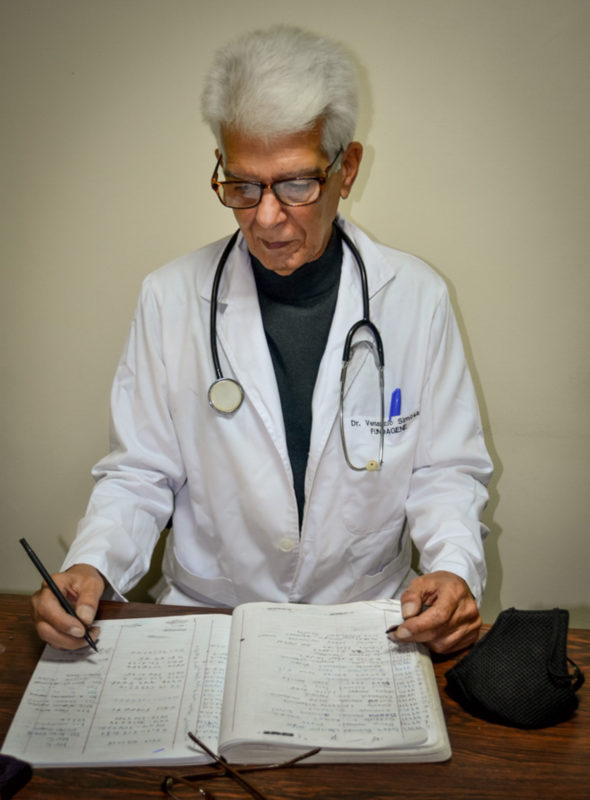

He had barely set foot outside the university premises when he received a message on his phone. It was a pediatric neurologist from Valencia, state of Carabobo, asking for his advice on a human genetics case: one of his patients had a peculiar physiognomy, as if he suffered from a cognitive-degenerative disability, but showed symptoms that could not be associated with a common diagnosis: frequent seizures, hypertension, and poor mobility.

“I would like to rule out a rare disease, doctor. I’m forwarding you the medical report and some tests so you come up with a diagnosis. Should you need further information, please let me know.”

Medical genetics is not a very popular career in Venezuela. The specialty focuses on the detection and diagnosis of rare diseases and pathologies that have their origin in a patient’s DNA and chromosomes. Dr. Simosa has dedicated his career to treating diseases that many medical professionals see only once in their lives, and that is when they study for a university exam.

He called the medical geneticist Isabel Fernández, his assistant in the university courses.

“I guess you are already aware that we won’t be teaching more courses,” he told her. “So, I need you to pass my phone number and e-mail address to all the doctors you know. Let’s see if we can arrange for more consultations nationwide. If the students and patients cannot make it to Caracas, I will reach out to them, even if it is over the telephone.

Consulting with other physicians was not new to him. Ever since he graduated as a geneticist in 1981 and started teaching at the Central University of Venezuela and in different hospitals in Caracas —back when the average number of students in the postgraduate classes he taught was around 30 or 40 people—, he has helped other doctors diagnose rare genetic diseases.

But the number of professionals in the area is dwindling. In 2016, there were 56 medical geneticists in the country. The Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Research (IVIC) —where the first postgraduate course in human genetics was taught, back in 1975— reported a total of eight specialists registered in the entire country at the end of 2020. Most resided in Caracas and were over 65 years of age on average. And not all of them specialized in rare diseases.

The only institution where a postgraduate course in human genetics is still formally imparted is the IVIC itself, which is located in Altos de Pipe, near San Antonio de Los Altos, state of Miranda. In 2019, there was only one student pursuing the specialty. In 2020, due to the pandemic, classes virtually came to a halt.

Thus, Dr. Simosa is one of the few geneticists specialized in rare diseases still left in Venezuela.

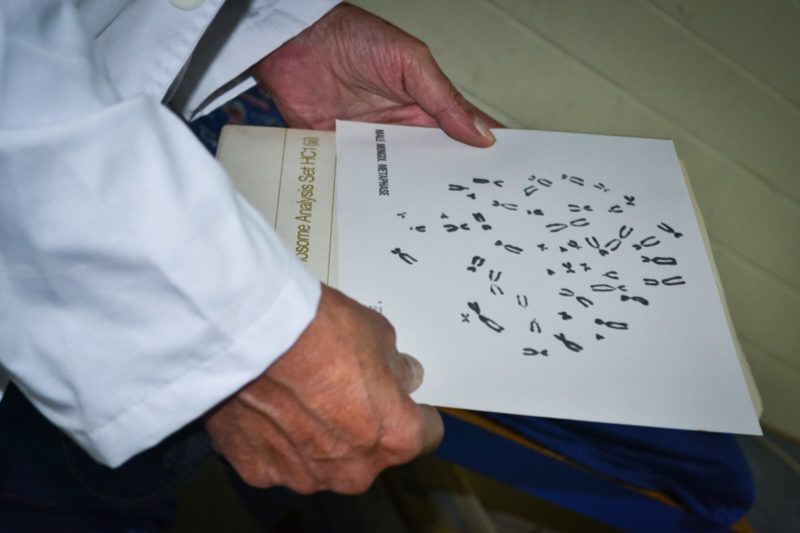

In December 1991, Dr. Simosa engaged in a field research, along with a multidisciplinary team, in several towns in the island of Margarita, where he diagnosed a neurometabolic disorder known as Mucopolysaccaridosis Type III, also referred to as Sanfilippo syndrome. From that moment on, he would travel to Margarita every yeaer to continue his research work.

With resources from the Institute and the assistance of local neighbors, he would see about 500 patients from La Asunción to Juan Griego.

He visited patients at home because one of the symptoms of the Sanfilippo syndrome is that the body is unable to break down certain sugars, which leads to poor mobility, cognitive impairment, and a peculiar physical appearance: coarse facial features, bushy eyebrows, a protruding tongue, as well as arthritis and chronic otitis.

He interviewed each family to determine if the children suffered from insomnia and recurrent seizures. He drew samples from both the children and their parents to test for consanguinity between the parents or other family members. The origin of the disease is genetic, so he had to determine whether or not the patient had inherited the condition.

According to the World Health Organization, mucopolysaccaridosis is a rare disease that only affects about 1 in every 2,000 individuals. Normally, parents have no sign of the disorder, but if they are both carriers, they pass on the faulty Sanfilippo gene to their child at the time of conception. It usually occurs in parents who are close relatives because their lack of genetic variety increases the likelihood that they will transmit disease-carrying genes to their offspring.

The disease that Dr. Simosa diagnosed in Margarita was a very strange form of the pathology. Some relatives of the patients also had dental growth abnormalities, intolerance to heat, and spots on the skin, which was thinner than usual. It was another disease with no previous record in the medical literature in the region: Autosomal Recessive Ectodermal Dysplasia. About 27 of the patients he examined over those years had the condition, and more than eight had the Sanfilippo syndrome. The rest were healthy or were carriers of the faulty genes but showed no symptoms.

He would collect data for 12 days or so and keep the blood samples in refrigerated containers for later analysis in Caracas. Once he received the test results, he would reach to each family and their attending physician and would explain them what was the disease about and why the patient had it, and then would suggest a treatment plan for a better quality of life.

Dr. Simosa made the trip to the island until 2012. As intent as he was in continuing his research in 2013, his colleagues and contacts had left the country and no local doctor knew where to locate the patients he had already seen or have an idea of the disease he was researching.

“Muco… what? For the life of me, I have never heard of the disease. We have never seen patients with those symptoms,” they would answer when he called them over the phone.

By mid-2015, Dr. Simosa had finished a training course in clinical genetics at the Doctor José Gregorio Hernández General Hospital in Catia, west of Caracas. The only noise in the classroom was the sound of the three pediatrics students’ chairs.

He went to the administration area and they asked him if he was going to teach a new course.

“How are we going to open the course with less than five physicians starting residency?”

“Don’t worry,” said one of the secretaries. We are going to add several integral community doctors to the list in order to complete the meet the minimum required number of students.

“I am sorry, but those people are not qualified to perform at the undergraduate level, let alone…”

“The government is pressuring us to include them, doctor,” the secretary interrupted him. “They are forcing us to offer them training because they consider them professionals. So, will you teach the course again?”

Just to be polite, Dr. Simosa told her that he would think about it, but as soon as he got home, he began to write a letter where he announced his decision to quit his job at the hospital and asked for his status as an employee to be changed to that of retiree. He was 66 years old at the time. His work as a professor there had come to an end.

He did not mull much over it. The next day, he submitted the document.

A couple of months later, they asked him if he could resume teaching because they could not find another specialist in the area. He was adamant that he was not going to go back to teaching there if there were not enough university graduates enrolled.

He still had his job at the Central University of Venezuela and was seeing patients at the Institute of Experimental Medicine. But, starting in 2016, funds to purchase the materials he needed to examine samples got scarce, and people stopped coming to his office because they could not afford to travel from the remote locations they lived to Caracas. The medical doctors could not either.

Silence in the corridors was still broken by the presence of at least ten pediatrics and pediatric dentistry students. Nevertheless, by the end of 2018, Dr. Simosa had no more students to teach. He guesses some of them could no longer pay their student fees and decided to drop out. Others might have moved to another country before or after completing medical school. The fact remained that he had not enough graduate students for another clinical genetics class.

Dr. Simosa sighs heavily, runs his hand through his white hair, and sits at his desk to finish typing a report on his computer. It is late 2020. He now receives an average of four cases a week of potential rare diseases, almost entirely referred by other colleagues.

In every physician he helps, he sees a new student.

His phone rings. A physician calls him to complete a consult.

“With the photos of the patient, the reports, and the medical studies I have been sent, it is clear that this is a case of mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA, one of the most common among the rare ones,” Venancio tells him. “Did you get the report and the texts on the subject? I emailed them to you.”

“I did, doctor. Thank you very much. Just one more question: what would the treatment be like?”

Dr. Simosa pauses before answering. He already knows what is coming next, but he wants to confirm anyway if the reaction is what he expects.

“Ideally, a routine pediatric check-up is in order, in addition to the corresponding immunization plan and visits to the cardiologist, the nephrologist, the nutritionist, and the endocrinologist.

“But the patient lives in Barquisimeto,” the other doctor replied. “You can’t even get those check-ups in Caracas.”

“I know. Unfortunately, if he wants to receive the full treatment, he must leave the country. There is no other way around it.”

Esta historia fue desarrollada en el taller “Tras los rastros de una historia”, impartido a través de nuestra plataforma El Aula e-nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

Esta historia fue desarrollada en el taller “Tras los rastros de una historia”, impartido a través de nuestra plataforma El Aula e-nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

1870 readings

I am a communication and media student at the Central University of Venezuela and a musician in training. I have always thought that life is like a Bach’s fugue: a piece where a number of subjects tell a story in a unique way. My goal is to narrate that sort of counterpoint the best I can. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].