The afternoon of January 23, a day of citizen protests throughout Venezuela, Luis José y Alexander were caught in a violence swirl that took place in the middle of the town of Tinaquillo, Cojedes state. Trying to flee, the high school students were intercepted by national guards who beat them savagely and took them to the command. Not even suffering from scleroderma, a disease that rots his skin saved one of them from being imprisoned for six days. He is 16 years old.

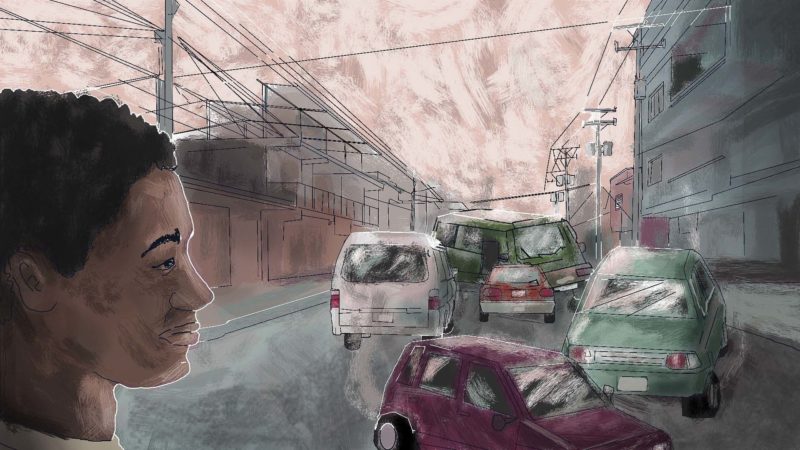

Ilustrations: Robert Dugarte

Ilustrations: Robert Dugarte

“Shoot and kill them,” one of the national guards was heard to say.

“Don’t do it, they’re students,” said the one who was pointing a gun at them.

-Shoot them, nobody cares about students.

And while the discussion continued, Luis José and Alexander had to ask themselves how they got in the middle of that situation.

Around 1:00 p.m. on January 23, 2019, Tinaquillo was a complete chaos. People were shouting and running. Cars and motorcycles drove in all directions without observing traffic regulations.

After 2:00 o’clock, it seemed that the situation had calmed down, so Luis José and Alexander, after leaving their high school, tried to return home to work together on the final project of a school subject. They took an alternate route to avoid the crowd. People were saying that the PSUV political party house had been burned down, days before its’ opening, and also the Casa de las Misiones (house that will be the center of government aid programs). The rumor was that a government’s facility had been looted, and that the downtown of Cojedes city had become a battle field. A river of people was running away from National Guards riding on motorcycles.

On the way, the boys saw that the Fonturco supply store had been looted. They detoured, the road was blocked, and took the Tamanaco street trying to reach the La Cruz sector. But after a few minutes they heard someone that shouted:

“Run, the motorcycles are coming!

The street was empty. They never knew were the shout came from.

“Against the wall!

Eight GNB officers had intercepted them.

“Put your hands up and pray”, Luis Jose told his friend when noticing he was paralyzed with fear and wanting to weep, while he prayed in silence.

One officer yelled:

“Lower your hands!” and one got off his motorcycle and punched Alexander’s stomach with a wooden board.

“Are you deaf? We told you to lower your hands.”

Luis José felt a strong blow to his ribs knocking the air from his lungs.

“My hands are down, please do not hit me again,” he begged.

“Go on, beat them that they can take it,” said another of the officers and began to beat his partner. He felt a hand squeezing his neck tightly and they shouted at him to raise his head, while another slapped him hard on the face.

His eyes clouded; the ground under his feet moved. They kept beating him. As he could, he recovered his breath and, seeing how they were beating Alexander with the board, he managed to say: “Do not block them with your hands and let them go on.” His arm swelled as when he was given shot and his skin got infected. Luis José knew very well what that meant, because he suffers from scleroderma. The skin rots when he gets hurt or does not have proper hygiene.

He does not know how he built up his courage, or where he got enough strength to demand the officer to stop beating his friend.

-So, now you are his lawyer, you’re going to get more beating with that attitude -and they began to hit him with the wooden board.

He chooses to say nothing. He also forgets about his illness. He only implores God for all to end. His legs faltered and, when he was about to fall, the officer grabbed him by the shirt and picked him up.

“Take off your uniform shirt, because if I arrive at the command with you in uniform, I’m going to get into trouble,” he ordered.

When he was taking off his shirt, another officer said:

“Give him some more that he can resist.”

And they gave him another blow with the wooden board on his back that made him fall on his knees. The officer picked him up, forced him to give him the shirt, wrapped it in his hand and threw it away.

“Get on the motorcycle and put your hands in your back.”

They took them to the police headquarters. And unable to do anymore, Luis Jose began to cry.

“Now you are going to cry? We don’t like gripers… Go there and take off your pants that I’m going to inspect you.”

He had nothing on him, only his wallet and his house key, as the officer corroborated seconds later.

“He is clean,” he said.

Then he threw away his pants. He was allowed to keep on his shoes, a short that he was wearing and no T-shirt. They spend more than three hours in the State Police Command in Tinaquillo, waiting for a convoy to take them to San Carlos, the state capital.

They were pinned down and one of the superiors began to curse them and to accuse them that they were the real guarimberos, those who blocked the streets and avenues.

“Look at you, without any shirt, I wonder how many stones you threw,” he told Luis Jose.

He could not take it anymore and he replied saying that one of the officers had thrown his clothes away, because he was wearing his student uniform.

“Do not reply to me, stand up and move to the truck’s edge”

In the way to San Carlos, one officer grabbed him by his shoulder and yelled that throwing him from the truck meant nothing to him, and when in case he was asked what happened, he would say that the boy wanted to fly, so he jumped and killed himself.

“I do not care doing that because you are a dam guarimbero.”

Again, he chose to say nothing, which trigger off a rifle-whip against his chest.

“Sit, and keep your head down or I’ll rifle-whipped you two times more.”

They were pinned down with their heads between their legs and their hands behind their backs. The truck was parked under the hot sun and they were not allowed to drink water.

They were taken to the Command of the National Guard of Los Mereyes, in Tinaco, where they were detained for five days.

During that time, the beating stopped, they were allowed to use the toilet and to receive food from their relatives. Some of the officers were friendly, and even gave them some advice and apologize by saying they were just following orders.

Realizing that he did not arrive home, Maryuril Gutiérrez, Luis José’s mother, began to worry. She went to his classmate homes to inquire and nobody knew about him. Her despair was so great, that she saw motorcycles and cars of the guard in the street, and she shouted to them for help.

When she found out where they had taken her son, she asked to speak with the commander. She banged the gate and made herself noticed, so when the commander finally went out, he asked her:

“Are you the noisy one?”

She replied that she was the mother of one of the boys who was detained and that he had a special health condition.

“That is not my problem. Do you have a health report? Where are the Child Minor Services, where are they?”

Her perseverance allowed her in. When she saw Luis José, she found him dirty and in shorts. That was her biggest fear, to see him like that, because of the scleroderma, which is an autoimmune disease that lets him with little body defenses. He has to take Methotrexate and Prednisone, and receives cycles of chemotherapy which weakens him.

On January 24, at his arraignment, she gave the medical report to the prosecutor and begged to isolate Luis José to prevent him from relapsing in his illness.

“I only ask not to mistreat him, because if his skin is hurt it can rot, – she explained later to the officers. His condition makes that any wound or blow will not heal well, he has no body defenses, and he can get an infection. The command of Los Mereyes de Tinaco looks like a jungle and, after seeing those conditions, she demanded that her son’s right to health be respected, but the officers reacted with a question:

“Are you a doctor?”

She answered, she was not.

“But I am his mother, his nurse, his everything; I am the one who knows his condition better than anyone”

After insisting, they allowed her to see him. He was shaking because he was nervous and lacking his treatment. She wanted reassurance that his back and shoulders had not been touched, because he already had an infection and it took time to heal. She gave him food, and after that she was not able to see him anymore.

His doctor told her: the next 48 hours are decisive. On Thursday, his health began to deteriorate, she sensed it, she knows him.

Friday the 25th was the arraignment. The prosecutor requested the release of two high school students, as well as nine more teenagers arrested in the middle of the protests on the 23rd. But the judge denied the motion and asked for guarantors that earned three minimum salaries and had no criminal record.

The prosecutor requested Luis José to take off his shirt, to show the blows he had received, but the judge did not pay much attention. He went in and out of the room, until he said:

“I am the law here, and your children are in my hands.”

He issued his judgment that meant that Maryuril could not bring her son back home.

On Saturday they called her to tell her that his condition had worsened. The officers took him to court, and there was no one to sign the order to take him to a hospital. Nor was the coroner. Finally, he was taken to the hospital in Tinaco. The woman doctor on duty did not want to treat him because of his condition, but after Maryuril’s plea she agreed to treat him. He had high blood pressure and a high fever. The doctor told the captain that the boy was in poor health and that she could not keep him there and had to be taken away.

On Sunday Maryuril went out early to see her son and his health continued to deteriorate. But not even then they released him. He had to wait until Monday, when he was dismissed with precautionary measures. He must appear each month in court. Days later and with the same measures, Alexander was also released.

Maryuril was spotted during El Pancartazo (a protest with banners) on February 2. It was her way of protesting about what happened with her son. Meanwhile, Luis José has been receiving hydration through an IV line in one of his hands. He is already in the clean environment and at the right temperature that his body so much needed.

Translation: Josefina Blanco

This story is part of the series Crecer en represión (Growing up in Represion), developed in partnership with the NGO Cecodap.

1649 readings

I am a Venezuelan journalist and an attorney. I have a degree in communication and media from the Cecilio Acosta Catholic University and I am a correspondent for El Pitazo from the state of Cojedes. I am passionate about reporting and I will continue to do so until my very last breath. If I were to be born again, I would study journalism because it is, to me, the most beautiful profession in the world.