Psychologist Gloria Pino —very tall and very thin, like no one else in her family— lived in pain and with fatigue and a pounding heart. She consulted with many doctors, but none would arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Until one doctor took her time to study her medical history thoroughly. That was the day Gloria first heard about Marfan syndrome, a rare disease that affects one in five thousand people.

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUM

PHOTOS: FAMILY ALBUM

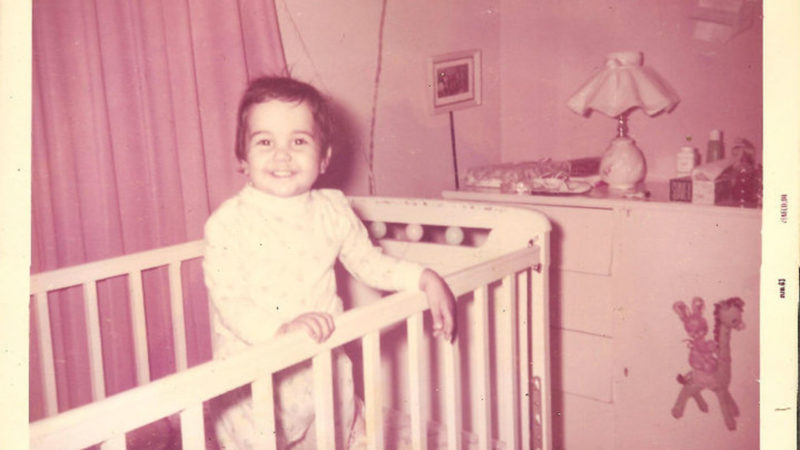

I am the last of seven children. Rather than parents, I would say I had grandparents, because when I was born my father was 67 and my mother 48. The sister who came before me, who was 11 years old at the time, used to tell me that I was adopted, which was not only cruel but also very intuitive on her part, considering that, deep down, I had always found myself wondering why I was so different. I was very tall and very slim, so much so that, when I was five, I stood over two heads taller than a nephew my own age and I reached the height of my adult sisters’ bustline. My hands and feet were also very long. I looked for those features in my relatives, but I couldn’t find them.

At school in Maracaibo, I was always at the end of the line, which made me the dream of my physical education teachers. At the age of 13, I was 5 feet 8 inches tall —3.2 of which were legs only— and had an arm stroke longer than my height, and huge hands; so, in their minds, I was predestined for basketball or volleyball.

But volleyball was pure torture to me because I have always been clumsy. My ankles seemed to be made out of rubber and I couldn’t stand straight on my feet without them bending. That was also the case with my hands: when the ball came at full speed, my fingers, instead of returning the object to the opponent’s area, flexed towards the back of my hand, against all anatomical logic, after which I would be left in pain days at a time.

My experience with basketball was no different. Sprains and extreme fatigue, which barely allowed me to survive a single regulation period, put an end to my teacher’s dreams and my sports-induced torture. But I still had to pass 12th-grade gymnastics.

I think I’m the only person in my school’s history to have flunked gymnastics, the reason being that I was “lazy” and didn’t complete all the exercises. But you can only imagine what it meant to me to have to stand on the balance beam with my hypermobile ankles. Or doing a handstand with arms so thin that they looked like skin glued to the bone: my bones and joints just couldn’t deliver, and I would end up falling strepitously. Someone must have taken pity on me because I passed the course at a makeup test.

The routines of my daily life were frequently interrupted, albeit shortly, by bouts of extreme fatigue, fainting, excruciating joint pain, or by a heart that would race for no apparent reason. Because of the symptoms, I was examined by all the specialists my parents could find, under the guidance and with the support of Dr. Pedro Iturbe, my father’s best friend. Unfortunately, neither that pilgrimage, nor the good intentions of Pedro Eme, as my dad called him, would shed a light on whatever was wrong with me.

I remember the visits to Hogar Clínica San Rafael, with its towering ceilings and long corridors. They examined my feet, my hands, my arms, my spine, and, there too, I complained of the agonizing pain in my legs that woke me up in the middle of the night. “Growing pains,” they said. They claimed my double curve scoliosis was caused by the weight of my school backpack. My hands and feet? The fact that no one else in my family had hands and feet as bony and long as mine was nothing to fear.

I had my first boyfriend towards the end of my adolescence. He was a medical student. One afternoon, while chatting on my house’s porch, he saw my chest jump. Concerned, he asked me if I was feeling okay, and I told him that my heart would jump like that and without any effort on my part. “That’s not normal,” he said. My parents took me to a cardiologist, who said he heard ‘a murmur’, an issue that my father and one of my sisters had had to deal with, and prescribed me an antiarrhythmic drug for a month.

At the age of 22, I had my baby. It was a natural childbirth.

Dr. Gerardo Fernandez had been my sisters’ OB-GYN and the one I went to for my prenatal care checkups. My son was born at dawn on January 16, 1985. Everything was going as expected, until I had to push: count 1, count 2 and… “I can’t go any further,” I said. I was consumed with exhaustion and had no energy left to finish pushing. So, Dr. Fernandez had to apply pressure with his body on my abdomen for my son to come out.

Having just graduated as a mother and a psychologist, I dedicated myself to those roles. The fatigue wouldn’t stop. I had the occasional bout of prostrating back pain; sometimes it was so severe that I would faint. I went to a traumatologist with my latest spinal X-ray. He took a look at the report and asked:

—“How old are you?”

—“30,” I replied.

—“There must be something wrong with this report. You are too young,” he said, as he read the X-ray on the negatoscope.

After a long pause, he added:

—“Well, the report is right, but it is very rare for people so young to have generalized spondyloarthrosis. I’m going to give you an injection of methylprednisolone, but we will only use it for crisis like this one, and not more than twice a year.

The treatment worked, but I was left thinking about the doctor’s reaction to the fact that someone my age could have spondyloarthrosis. Was it something that was affecting several of the systems in my body or some kind of disease that was aging me prematurely? I would ask myself. I decided to go to an internist with my questions and tests. Unenthusiastically, he looked at the tests and diagnosed me with hypochondriasis. I left his office with more doubts than I had when I came in. As a psychologist, I have always believed that it is important to take care of one’s mental health, and back then I was seeing a therapist regularly. During a session, we discussed the internist’s diagnosis and didn’t agree much with it. It was true that my symptoms were causing me anxiety, but they were real. The tests were there to attest to it.

The pain crises returned. One day in 1992, after a fainting spell, a good friend recommended I visited endocrinologist Belinda Hómez de Delgado. Truth be told, I didn’t have much hope and I couldn’t see how an endocrinologist would help me with that and other symptoms that had me touring doctor offices, but I went to her nonetheless.

Belinda received me in Clínica Paraíso. She was a tall, slender, elegant woman; she spoke slowly and listened attentively. She examined me for two hours, in great detail, as no one had ever done before. She started with my family history, asking about my close relatives’ ages and health and about my parents’ cause of death. She then proceeded with the physical examination. She was quiet and focused. She measured the distance of my open arms from the fingertips of one hand to the fingertips of the other, and recorded my height and weight; she also looked at my hands, like so many others, but she paid close attention to the flexibility of my long bony fingers and asked me to flex them in ways I didn’t know I could; she examined my feet and the bunion surgery scars on them; she listened to my heart and the noise it made because one of its valves was not closing properly; she checked my spine X-rays and images and analyzed its curvatures, the multiple cysts I had in the lower part of the spinal cord, and my disc degeneration; she examined my skin and all the stretch marks that had been carving into my knees, thighs, hips, breasts and shoulders since I was a child, and also those that appeared during my pregnancy. She finally said:

—“I’m not a geneticist, but I think you have a rare disease known as Marfan syndrome, which is caused by a new mutation, probably due to your parents’ age. It seems that no one else in your family has had it and that you are the first case. Your son needs to be evaluated.”

I didn’t say a word. The whole thing was very difficult to understand. She went on:

—“I think it’s Marfan syndrome because that would explain the length of your hands, feet and limbs, as well as the stretch marks you have had since you were young, even though you have never been overweight. Many people with the condition also have joint hypermobility, meaning that the joints have an unusually large and wide range of movement, which may have some advantages but, in the long run, causes deterioration, pain and stiffness. And, as in your case, people with Marfan have very little muscle mass and find it very hard to build it and maintain. Any doubts or questions?”

—“Not for now,” I replied.

And it wasn’t that I didn’t have any: it was that I couldn’t think clearly.

She continued:

—“Listen to me carefully: skin and musculoskeletal disorders can cause discomfort and pain, but there are two particularly important elements that we need to pay close attention to: the eyes and the heart. Most of Marfan patients have eye lens issues that you haven’t complained of so far; you need to get yourself checked by an ophthalmologist with experience in cases like this. Most importantly,” she added, “Marfan affects the aorta and the heart valves; so, you must see a cardiologist as soon as possible, who will perform an echocardiogram and an arrhythmia evaluation and will control your blood pressure to protect the aorta.”

I stood there, still in silence. I was both relieved and in fear.

—“I know it’s a lot of information to process, but the most important thing for now is to have you examined by a geneticist, a cardiologist and an ophthalmologist.”

I left her office, walked through the dark parking lot (it was dusk already), got in my car and cried. I finally had the answer I had been looking for. It was the explanation to all my symptoms, to all my discomfort. The downside was that it had come with a whole bunch more questions.

At first, the diagnosis did not bring much relief to me. That word, ‘mutation’, echoed in my mind. I’m a mutant and a freak, I thought.

I followed Dr. Hómez’s instructions. Dr. Heber Villalobos, an eminent geneticist from Maracaibo, confirmed her suspicions and also ruled out that my son had the syndrome. Carlos Augusto was a different slim and tall: this time around, different meant normal. It turns out that half of Marfan patients pass on the condition to their offspring, but my son is in the other half of the odds.

As for my heart, clinical cardiologists, interventional radiology specialists, surgeons and internists from the Institute of Cardiovascular Research and Studies of the University of Zulia and from Hospital de Clínicas Caracas took very good care of it. My mitral valve had a huge prolapse whose weight prevented it from closing properly, causing the murmur I had been diagnosed with years ago. And my aorta had begun to dilate, which led to my first heart surgery in 2004, during which Dr. Klaus Meyer and his team repaired my mitral valve, replaced part of my aorta with a Dacron sleeve, and implanted a pacemaker. I had another operation a couple of years later to replace my aortic valve, which had also been damaged.

My eyes were for many years under the care of Dr. Alfredo Añez, who ruled out that I had the typical problems of Marfan patients, namely early-onset cataracts, severe myopia and lens dislocation, which could lead to vision loss.

I learned to live in pain because I always have some, which has made my pain threshold higher than other people’s. Apparently, one of the deviations of my spine ‘compensated’ for the other and I have been stable. Needless to say, I wear spine ergonomic devices and maintain a healthy body weight. Marfan is a rare disease that affects one in five thousand people. There is no cure and no treatment that can reverse the damage caused by the mutation, at least for the time being.

It has been 30 years since that consultation with Belinda, as I now call her with great affection and respect. I live in Spain with my husband, who also has Marfan syndrome. Time helped me understand that I was not different. That I was no mutant or freak, as I feared.

And I am still the same person; only now I have more information on how to take care of my health and make good decisions.

This whole experience of learning how to live with a rare disease has also given me a purpose: to provide valuable information to people affected with the condition and their families, because informed patients take an active role and responsibility for their own health. I have since dedicated part of my time to patients’ associations, to working for our rights, to seeking better services and, above all, to networking.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

871 readings

I was born in Maracaibo, where I studied psychology and practiced as a professor and a researcher until 2015, when I moved to Spain. Since 2010, I have dedicated part of my time to working with organizations that empower rare disease patients.