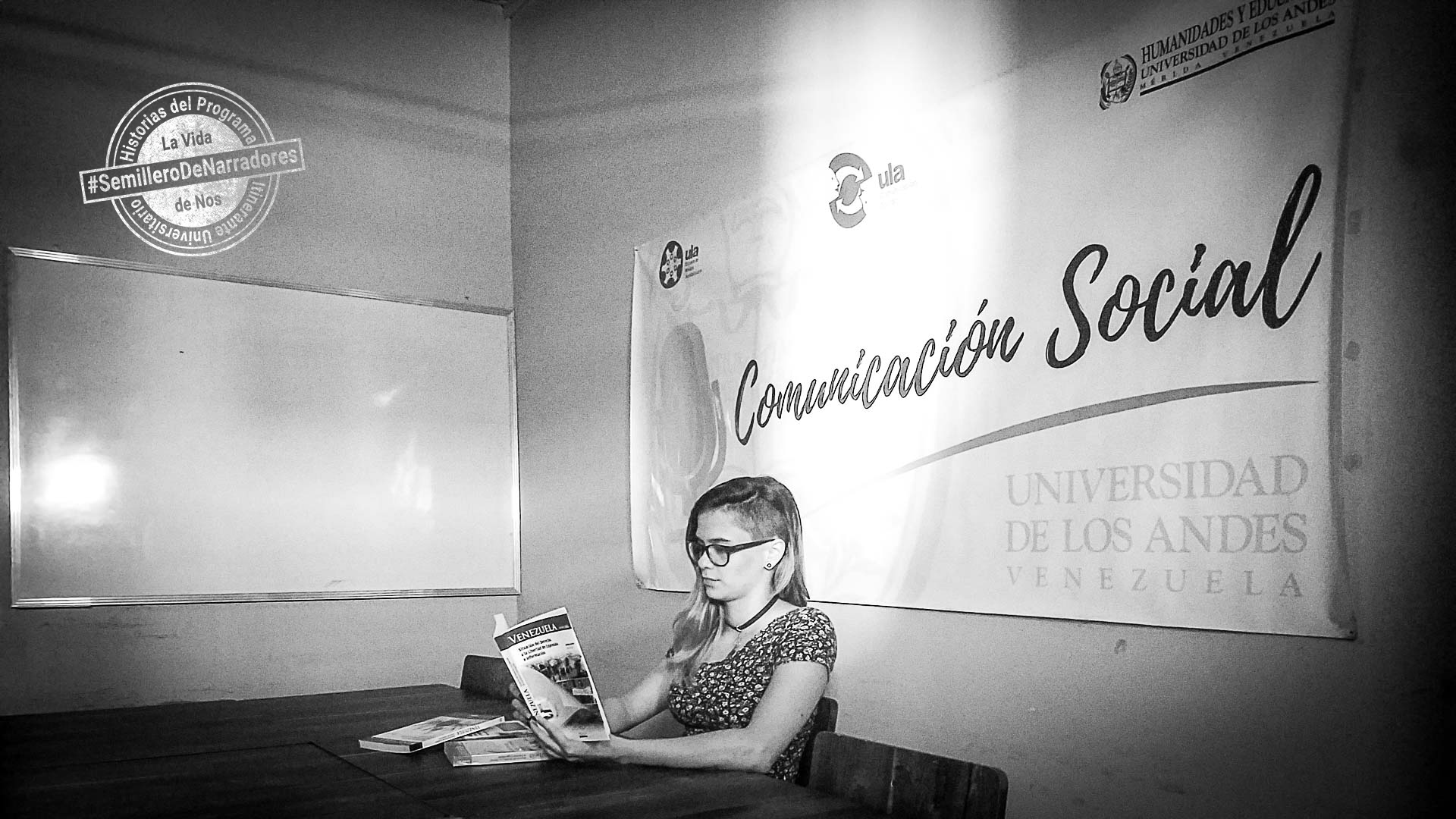

The first cohort of candidates to a bachelor’s degree in Social Communication at the Mérida campus of the Universidad de Los Ándes began classes in July of 2016. It was made up of 25 students. Three years later, there are only eight left. Paula Rangel is one of them. In this photostory from the #SeedbedOfStorytellers of La Vida de Nos, Paula describes how the classrooms she studies in have been emptying out.

The first cohort of candidates to a bachelor’s degree in Social Communication at the Mérida campus of the Universidad de Los Ándes began classes in July of 2016. It was made up of 25 students. Three years later, there are only eight left. Paula Rangel is one of them. In this photostory from the #SeedbedOfStorytellers of La Vida de Nos, Paula describes how the classrooms she studies in have been emptying out.

We were 25 students when we first set foot in the classroom. It was July of 2016. To me, it felt somehow like a milestone… it was as if we were making history: ours was the first cohort of students of the Social Communication degree program at the Mérida campus of the Universidad de Los Ándes. Venezuela was already enduring a severe crisis, one that has been slow to die down; but back in those days, maybe because of the excitement of being studying the career I had chosen, the future looked promising.

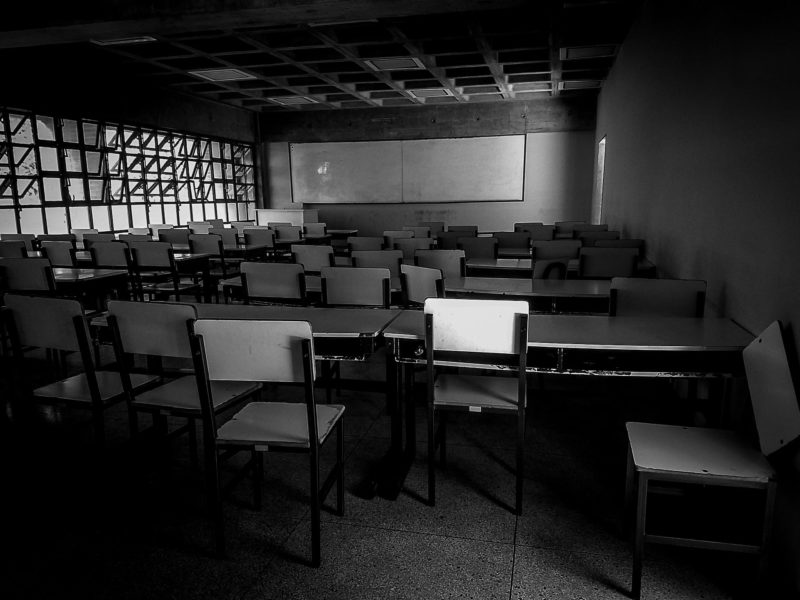

It didn’t take long for my classmates and me to forge a very strong bond. Not a day went by without us spending time together. We would see all our courses in the same classroom and with the same teachers, just like in high school.

It was also challenging, though. Our class schedule was very demanding and we only had 90 minutes to eat lunch. The food at the cafeteria was not exactly nutritious, nor did it fill us up. When they had no meat, we had to find something to eat to compensate for that, particularly the men, and that took time. Even so, and despite my living just 10 minutes from the college, I would rather stay at the university to have lunch with my classmates.

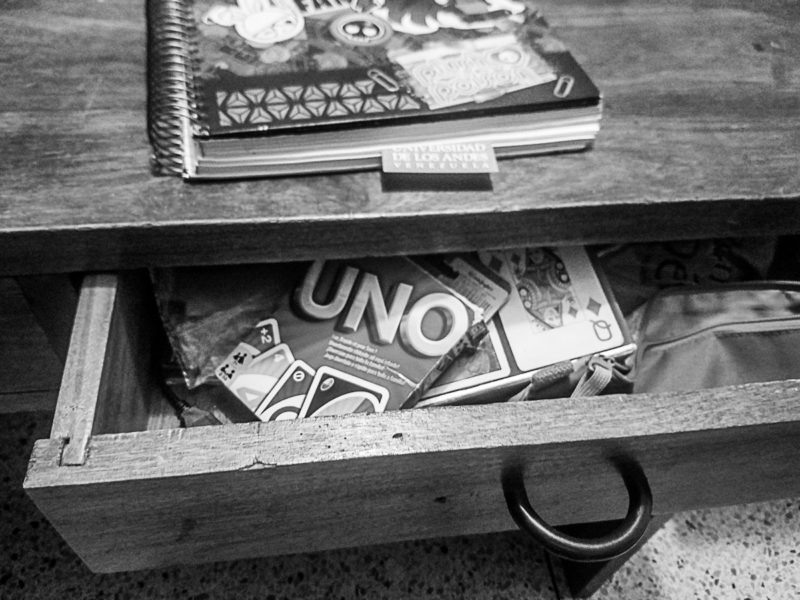

We spent most of our free time in a small forest-like area. We were always entertaining each other with our own stories or playing Uno.

Life was harder for those who lived far from the campus, like Simón, whose house was one hour away. Also, his family was financially distressed, so he had to start working when we entered our second year. He was tired, both physically and mentally, and it showed, but I admired him because, despite being the one amongst us having the worst time, he was supportive and inspiring.

Whenever I felt tired, I thought of him: he was always on time for class and joyful and made us laugh with his jokes. So, I would repeat to myself, “If he can do it, so can I.”

We would soon start complaining that money was tight, but that didn’t stop us from sharing. We were together at breakfast, during breaks, at lunch… And we used to go out for a coffee, or for a few beers, or for a milkshake, or for ice cream. Sometimes we’d go to someone’s house. Those moments were worth gold to us.

Yet, there was a time when many stopped coming, not because they didn’t want to but because they couldn’t afford it. We tried to help each other by splitting tabs: “I’ll pay half the check and you pay the other half”, we would say. The idea was that none of us would be left out.

Except that the crisis was getting worse and out of control. Protests erupted against Nicolás Maduro’s regime, and the university’s activities came to a halt. Regardless, since we were the firsts to study the career and our class was small, we managed to handle the situation by taking distance lessons, or by meeting at one of our houses, or at a coffee shop, to study.

We never stopped.

I remember that after the guarimbas, when people blocked off streets and roads with barricades, I went to the cafeteria for dinner and what they put on my tray was a single orange. There was also the issue of the public transportation strike: although the university put in place a couple of bus routes, they slowly stopped working because the buses needed maintenance and spare parts that the university could not pay for.

So, the professors began to leave. We could notice that they were disheartened, and I could not tell whether they were encouraging us to study or to quit.

That was when the idea of dropping out started to cross the minds of a few. We would encourage those who would voice their intention to do so and ask them not to give up… not to throw it all away. But we didn’t always succeed.

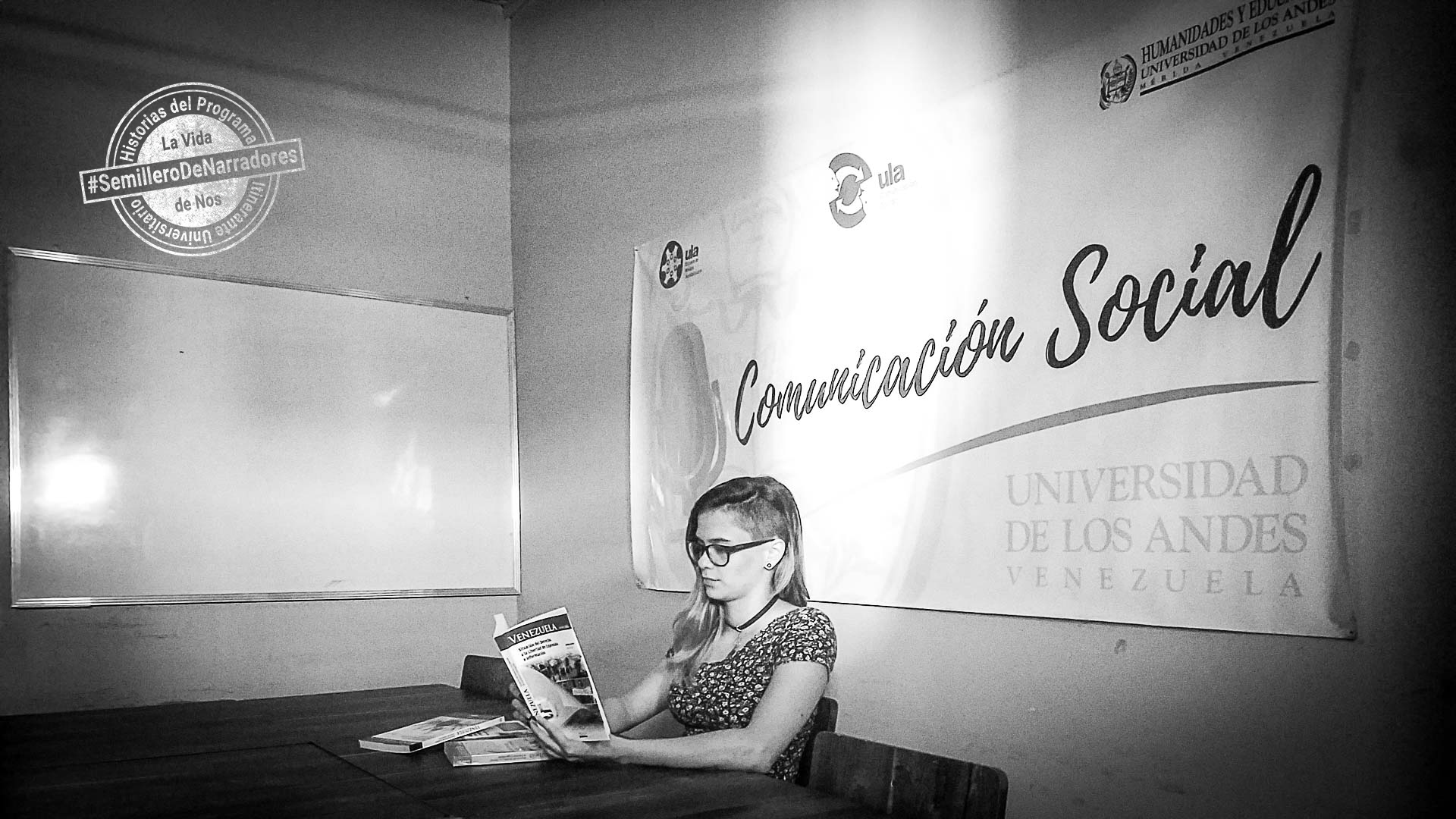

By 2017, when the second cohort of students of the Social Communication career was admitted, we had narrowed down to 18. We would think of those who had already left and wondered: Who would be next?

The constant university strikes, which were now joined by the professors, were the breaking point: we found ourselves at the crossroads of having to decide whether to continue or to quit.

Such was the dilemma on Simón’s mind, who was exhausted from working as a radio operator at night. I would lend him my sleeping bag to help him “rest better” when he was on-duty, but he was running out of energy… and jokes.

It wasn’t long before he left to Perú… by foot.

There were empty seats in the classroom, just filled with memories. My motivation seemed like a roller coaster at the time. I asked myself many questions. I too was considering the idea of leaving the country.

It was now 2018 and the classroom had already got too big for us: we were 11 in the third year. We hardly shared because none of us had time to hang out. I didn’t even know where my UNO letters were kept anymore. Our time together was reduced to the hours that we spent in class or in our journalism practices.

The year 2019 is about to end and there are only eight of us left.

How many of us will graduate?

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

1961 readings

I am 21 and a current student of the fifth year of communication and media at the University of the Andes in Mérida. I love extreme sports, particularly those where art and sports are combined. I didn’t think of pursuing this career, but I love it more and more, particularly because of its versatility. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

Un Comentario sobre;