Luz Marina’s father was one of the founders of Mene Grande, the town where the commercial exploitation of oil in Venezuela began, in 1914, located two hours from Maracaibo. She remains there. She cannot leave like many of her neighbors who are fleeing after the blackouts of March and April 2019, when their land became an impossible place to live in.

Photographs: Fernando Bracho Bracho

Photographs: Fernando Bracho Bracho

Luz Marina Pavón looks out from the small gate of her house, takes a look along the street and points out the many abandoned houses of Mene Grande.

“The boys who lived there, across from me, went to Panama”, she says. “The woman who lived in that house, migrated to Colombia. The man from the corner didn’t resist either and also went to Colombia with his children”.

She is not talking about the many people who had left the community in recent years. No. She is talking about the families that began to flee, one after the other, at the end of March 2019. Those who were convinced that you can no longer live in Mene Grande, even when this was the thriving town where, in July 1914, the oil well Zumaque I began to be exploited, giving rise to what would become the main economic activity of the whole country.

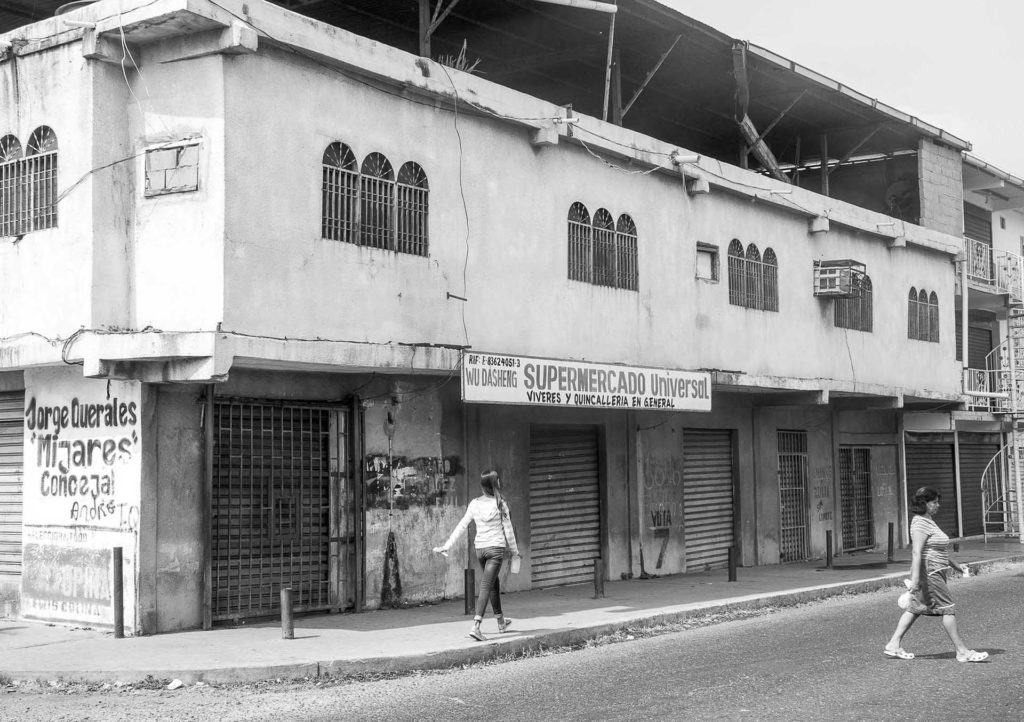

Before March 2019, Mene Grande was already a place plunged into scarcity, a decimated zone. Many shops had closed their doors. Only two of the four banks in town were still open. The public services barely worked due to the constant power cuts, and to the permanent absence of piped water, during the last four years.

But those were difficulties that people found a way to solve. So much so that they managed to dig holes in their backyards to extract water from underground wells –holes that go 15 meters down. Luz Marina, like all her family, gets her share of the well they opened on the plot of her sister’s house, which is on the same street. But during the March blackouts, many began to see themselves constrained: they had four hours of electricity every day, if they were lucky.

“We feel horrible. We have spent up to 14 days without electricity”, says Luz Marina.

Days without communications. Days that pass heavy and slow in a suffocating heat of more than 30 degrees. Days that leave a trail of fatigue and exhaustion. Days in which it seems that the world has stopped spinning.

That is why many people packed their bags and left from one day to the next. Some barely had time to say goodbye to Luz Marina, who has decided to stay put.

“My father was involved from the beginning, when Zumaque I began production … ” says the woman with brown skin and a sparkle in her emerald eyes that never goes out.

From Zumaque I, located in Cerro La Estrella, they extracted up to 2,500 barrels per day, which were then taken to the San Lorenzo refinery. This was the first refinery in Latin America, with a capacity to process up to two thousand barrels per day of oil, pumped by steam in those days. Today, Zumaque I is only a nodding donkey pump painted with the national tricolor, whose production is symbolic: between 12 and 14 barrels per day.

Sitting next to José Pirela, her partner, Luz Marina speaks under the trees in the middle of her backyard. There are plants of all sizes and all colors, and their shade offers a bit of relief from the heat of Mene Grande. The town is at the heart of the Rafael María Baralt municipality of Zulia state. Its streets of fractured asphalt meander among hills or twist between houses eaten by the sun and old buildings from the golden age. Those are the years that Luz Marina evokes with her slow speech. A promising past to which the history of her own family is linked.

“My father was one of the workers who participated in the founding of the town”, she says.

Her father told her many times that everything started there without machinery. The buildings were built with the help of donkeys that carried the stones from one place to another. The roads were opened with machetes, enduring the mosquitoes. It was the rural Venezuela in which modernity was just a vision. In search of that modernity legions of engineers arrived to extract oil without rest. And then came the nationalization of the oil industry, in 1976, decreed from the same Zumaque I. The nationalization supposedly would leave more income to the country and, of course, to Mene Grande.

Luz Marina speaks with pride and nostalgia, a lot of nostalgia. And she asks the questions that many are asking themselves in this area and throughout the country.

“How did we get to this? How can we live in these conditions?”

It is 8:00 in the morning of April 12, 2019. While Luz Marina talks, she looks at the interior of her home: she looks anxiously at the small bulb of some household appliance, some light still on, any signal that indicates that the electricity has not gone out for the umpteenth time.

During the blackouts, she has felt more closely the food shortages. Sometimes, she manages to mitigate them by buying vegetables from the truck, coming from Trujillo, which passes by her house every day. That’s when she has money to pay them, because getting cash is becoming increasingly difficult. José, her partner, who is the one who supports the household working as an electrician or a plumber, has not been able to work lately because of the blackouts.

During the nights without electricity, in the dark, they sleep outside the house, on a mattress under a zinc roof, and at the mercy of the mosquito clouds. Luz Marina can barely sleep when two of her granddaughters stay with her. She spends the nights trying to shake a piece of cardboard, as an improvised fan, so that their granddaughters fall asleep and stop asking, again and again: “Grandmother, when will the electricity come back?”

Luz Marina, exhausted, has also considered the idea of leaving the land of Zumaque I. She would like to spend time with her children, she misses them so much. Four of her five children emigrated three years ago and are more than 934,000 kilometers from Mene Grande. They are scattered in different areas of Bogota, the Colombian capital. David, Sara, Erika and Andreína, between 23 and 36 years old, insist that she leave, that she will be better there. They tell her that, at least, she could spend a few days with them so that she can forget the daily tragedy that is her life in the town.

But for 18 years she has been in a relationship with José Pirela and that is a decision that they should take together. They have discussed many times the possibility of starting from scratch in Colombia, with their children. But it is not easy. He does not want to leave the house alone, because he knows that the house could be burgled.

“A stepson left the house to his sister-in-law to take care of it, but since he delayed the payments he promised, she threatened to sell some things from the house to collect the debt. Luckily she didn’t do that, but she almost did it. Imagine, if the family itself is capable of doing something like that, how can I leave my home abandoned?” says José while Luz Marina nods.

José’s main reason for staying, however, is not only to guarantee the safety of the house, but also that he does not want to separate even more from his mother, an 80-year-old woman with high blood pressure who lives in Maracaibo, two hours from Mene Grande. He fears that something will happen to her and he will be far away.

Luz Marina understands this and that is why she believes it is unlikely that they will leave. In addition, their other daughter is a teenager who just started high school. And although her classes have been interrupted several times due to the blackouts, they believe that it is better that she finishes her studies here.

José predicts, however, that things may get worse. For example, he says, adopting his technician’s voice, that there are only 40 centimeters of water left in the well.

“We will have to dig deeper. You have to pay someone about 100 thousand bolivars to dig a meter more down, and buy a pump of at least one horsepower. We are worried about that, we have no way to pay for it and we would run out of water. Without water, it’s going to be as serious as being without electricity”, says José.

Touched again by nostalgia, Luz Marina gets some pictures of her family from a trunk. Her eyes are watering as she remembers every moment frozen in the images. She stops at one that transports her to Christmas a decade ago: her mother and father, her brothers, nephews and several friends, all of them are together in the picture.

She is overwhelmed looking at the photos. And her granddaughters, 6 and 7 years old, gathered around her, begin to ask her:

“Grandmother, who is this?”

She remains absent while offering a brief response.

“My father.”

The same man who lived in a town that is no longer this one.

There he is, in the center of the scene. Luz Marina thinks he looks very handsome in that picture and says again how much she misses him. She points with her finger to the family members that surround him in the portrait and that are now scattered around the world. Only 10 of the 30 that were smiling in that image are still living in Mene Grande.

Now she wonders if her granddaughters will also leave. They cannot know. Not yet. The children are now dancing around the backyard like butterflies fluttering, oblivious to the fact that they live in what was the cradle of oil production in Venezuela.

At some point, a melody comes to Luz Marina’s mind.

“Cántame una gaita, hermano, que ya llegó Navidad/ yo no quiero soledad en el alma del zuliano…” [Sing me a gaita, brother, as Christmas is here / I do not want solitude in the soul of the Zulian people…], she whispers.

And her eyes fill up again, as if she were about to burst into tears.

Translation: Raquel Rivas Rojas. Edition: Katie Brown.

1947 readings

“I think with my fingers, armed with 27 letters.” I am a bachelor of communication and media from the University of Zulia. I write about the stories that, every single day, erupt from a sometimes implausible reality.