Adrián Rodríguez will not have his First Communion nor play soccer again and he will never be a policeman as he dreamed. He was murdered by a “sniper”. On July 30, 2017, he died by a gunshot to the head when he was watching a demonstration against the Constituent Assembly in Táchira state. He was the tenth victim of that day. He had just turned 13 years old. The story of that tragic day is told by the narrator Oscar Marcano.

Illustrations: Ana Black

Illustrations: Ana Black

A sniper can be described as “a soldier skilled in camouflage and an elite shooter who fires a weapon at great distances to selected targets. Typically, and ideally, a sniper approaches the enemy (who is not aware of his presence), uses one or two bullets for each target and retreats without being seen.”

Maybe the murderer of Adrián Rodríguez does not strictly cover this description. Maybe sniper was just the nickname that unarmed neighbors used to dub the officer that, with a weapon of war, blew off the head of a 13 years old child in the vicinity of his own school.

It happened in the context of the elections of the questioned Constituent Assembly, a process that bypassed 70 of the regular steps guaranteeing the integrity of an election and was unrecognized by at least 40 countries. People took over the streets to protest and the security forces began to suppress. Adrián was not part of the demonstrations.

Despite witnesses claim that an officer of the Plan Republica – the name of the military operation that the Venezuelan Armed Forces usually apply during electoral events – was the one who fired from the school’s roof, local reporters assure that the perpetrator has not been identified by the authorities. The case is in hands of the Prosecutor’s Office 16.

Adrián was a quiet teenager, a soccer fan. He was born on June 5, 2004 as the youngest of six siblings. Son of José Rodríguez, bodyworker, and Noraima Sánchez, devoted to household chores. He lived in Colinas de Bello Monte, a popular neighborhood of Capacho Viejo, a town located on the road to San Antonio del Táchira, just over 30 kilometers from the border with Colombia.

To reach to the green house, with purple walls and red sofas, you have to climb more than one hundred steps on a hill that reveals wide pastures. Capacho was founded in 1602 and destroyed by an earthquake in 1875. After the natural disaster, its inhabitants took refuge in a neighboring farm, from where they rebuilt it. Capacho is the birthplace of Cipriano Castro, the famous “cabito“, a caudillo and president of Venezuela from 1899 to 1908, who began the so-called Andean hegemony that lasted until 1945.

Adrián was home-loving and shy. Visiting the grandparents, playing soccer with their cousins and watching cartoons were his hobbies. He was not in the phase of fancying girls, but he loved pancakes. He didn’t speak too much, “you had to force his words out”, according to his mother.

He had just finished the sixth grade and was very excited. His father says that the day he was going to take the picture required to enroll in first year of high school, he wore the basic education blue chemise. “He stood next to me and said: ‘Hey, old man, how do I look?’ I told him: ‘Pacho, you look good.’ I called him like that to annoy him. ‘But you have to iron the shirt,’ I said, and he said he didn’t care, that he was going to use it like that. That was in June, just beginning vacation.”

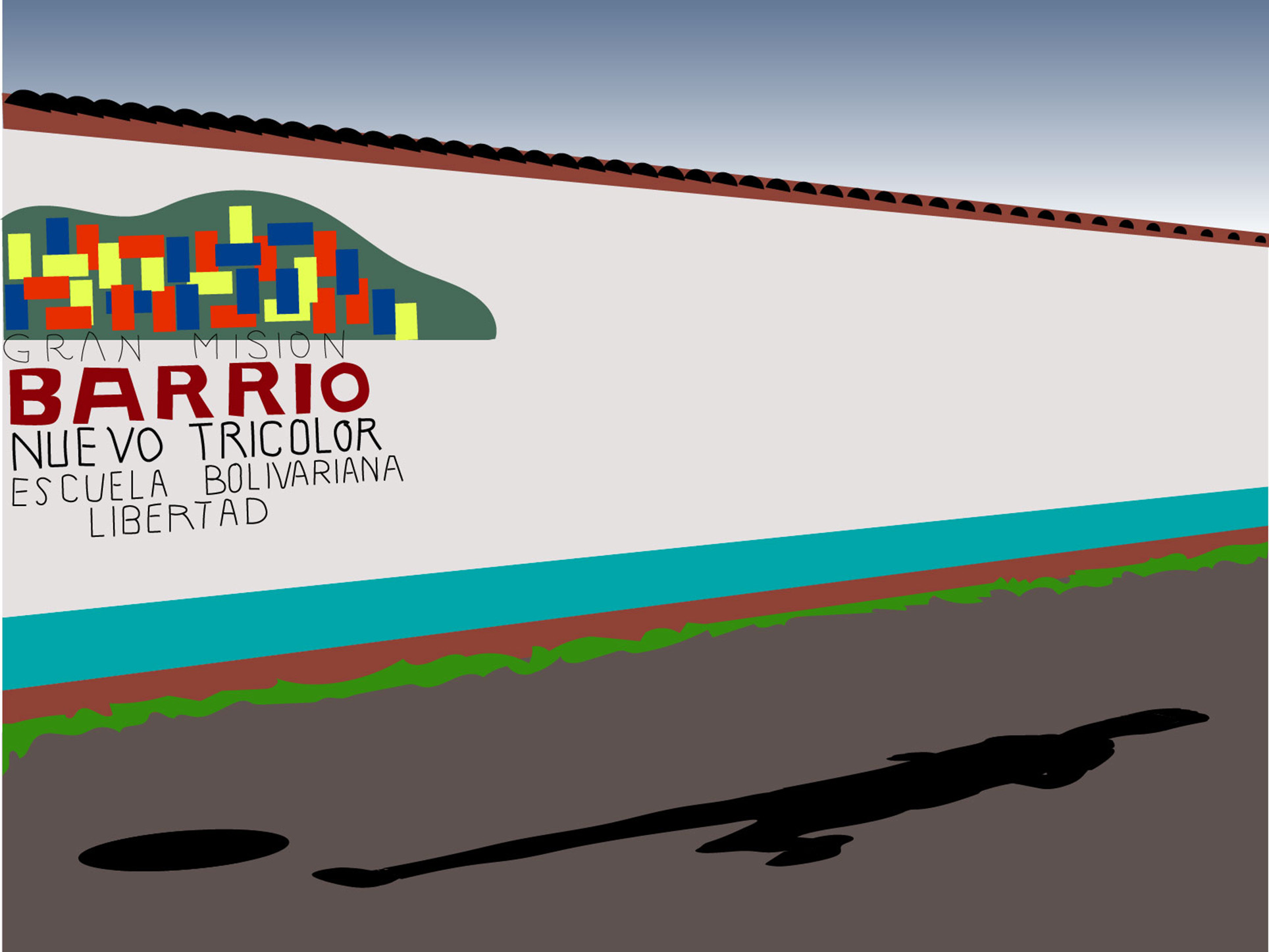

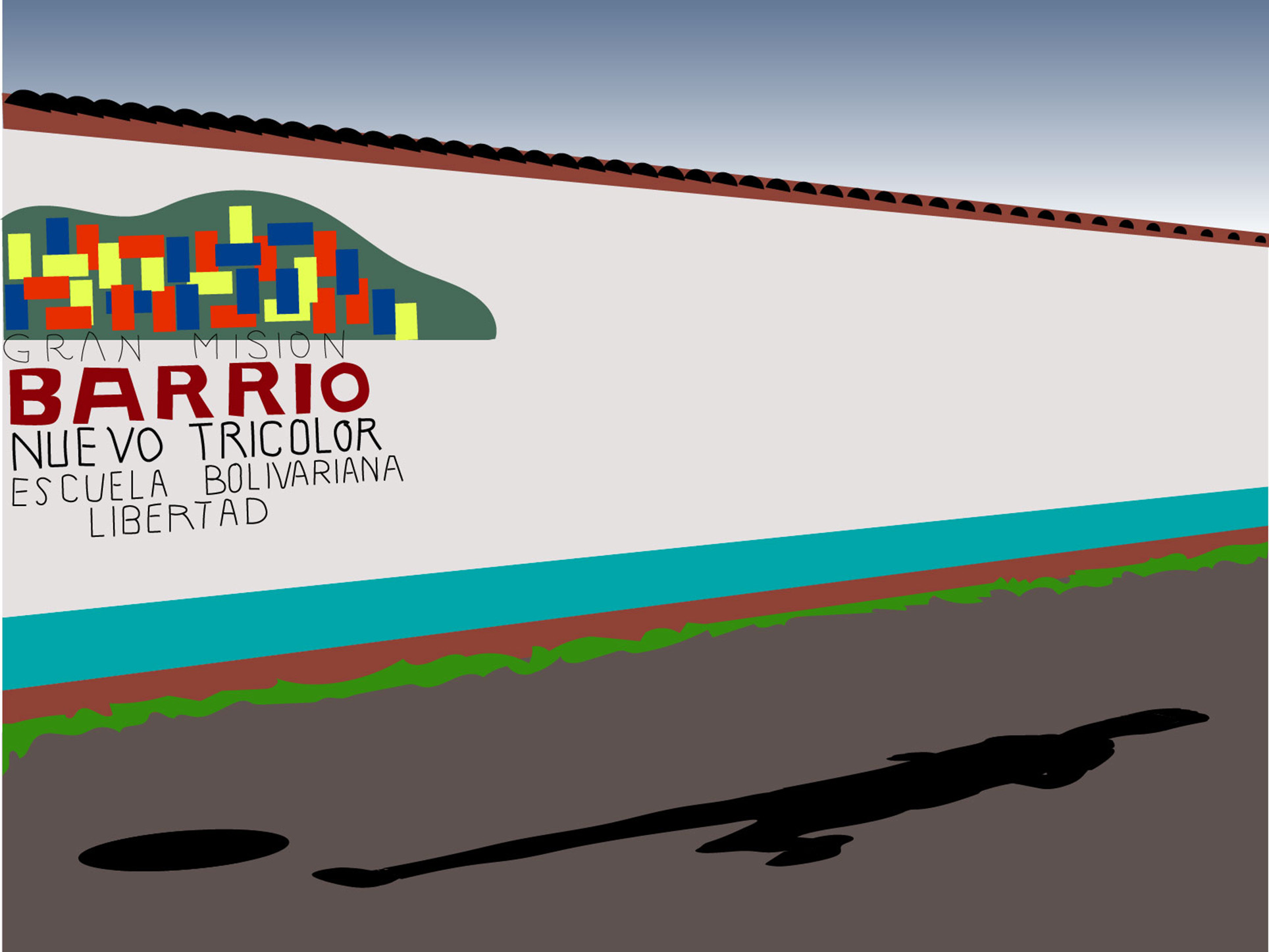

On Saturdays he went to catechism classes in church. He was preparing for his First Communion in December. His uncle Acevedo Rodríguez, Jose’s brother, was the one who spoiled him the most. Every morning he took him in his SUV to school, the Escuela Bolivariana Libertad. And during the afternoon, they ran errands together.

He wanted to be a policeman. A PTJ detective, says his father. Of the Body of Scientific, Penal and Criminal Investigations. “I used to tell him that if he wanted to be a PTJ, he had to study and not fail any year. And that I hoped may God give me enough to live to see him graduate as a PTJ.”

He had a well-built body, tall and had been part of the track and field team. In sixth grade he was taken to Rubio to compete in racing. “When he was in fourth grade,” explains his father, “there was cycling competition and they took him there, too. He came second. He also sowed. At school they grew gardens and he liked those things.”

That early Sunday, Adrián got up and visited his grandparents. Then he went with his uncle to pick up Noraima at the market. When he got home, he had breakfast with his family and then went back to his grandparents. At 1:00 pm he went for a walk around the town.

“He was not the gang type,” Noraima says. “I do not know why he decided to go out precisely that day. He had never been in protests or left the house; probably, curiosity is the only reason why he was there that day at school.”

According to several neighbors, opposition groups had begun to concentrate in the vicinity of the Escuela Bolivariana Libertad at noon, in protest against the Maduro’s constituent assembly. Military personnel who were on the roof of the school facilities were teasing them. Tempers heated up. Around 2:00 pm some protesters threw a mortar at the school, to which the military responded with gunfire. Adrián fell in the middle of that attack, he was shot at the head. He was more than 100 meters away.

After the death of Adrián – Jose says -, the officer who fired continued provoking the demonstrators: “he raised his rifle daring them to come closer.”

José was not there. The neighbors told him about it.

“We were with the grandparents when they broke out the news that someone of the family had been shot,” says the mother. A nephew of Jose went out to see what happened, and realized who was and came back with the news.

They could not believe it. Their youngest son, the most withdrawn, the one who never left home, was the victim. They ran to the site and found him lying on the sidewalk, next to a cyclone mesh fence.

“I do not know why that man did that,” Jose regrets referring to the officer that shoot at him. “I do not know if he, at that moment, thought on his own kids or even whether he has any. He killed a kid and he, the person who killed Adrián, should not sleep peacefully for what he did.”

The counterpart began to spread rumors. That Adrián was part of a gang. That he had died in a reckoning. That he had weapons.

“His weapons were a notebook and a pencil,” says Jose.

Despite the fact that the witnesses claim that the killer was an officer of the Plan República, nobody has been charged. The father has spoken several times with the prosecutor 16, but she has not given him any specific information, “if the killer was an Army officer, a member of the Plan Republica or anything.”

With research of Manuel Roa.

Translation by Josefina Blanco

This story is part of the series They were only children, developed in partnership with the Community Learning Center (Cecodap) and the support of El Pitazo.

1865 readings

I used to think that chance was tricking us into believing that it was in charge of things, but the truth is that it was pure causality. Now I write as if I were putting together a puzzle, perhaps imitating the one who plays the one we are.