The Venezuelan Federation of Psychologists launched a program to offer free emotional support to people who could feel overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As he had done in the past with other volunteer services, Román González joined the initiative. He is currently the only psychologist taking requests from the states of Anzoátegui, Sucre, and Monagas.

“Good evening. I am Román González, a psychologist from the Federation of Psychologists. It is time for our session.”

That is how he starts a new call.

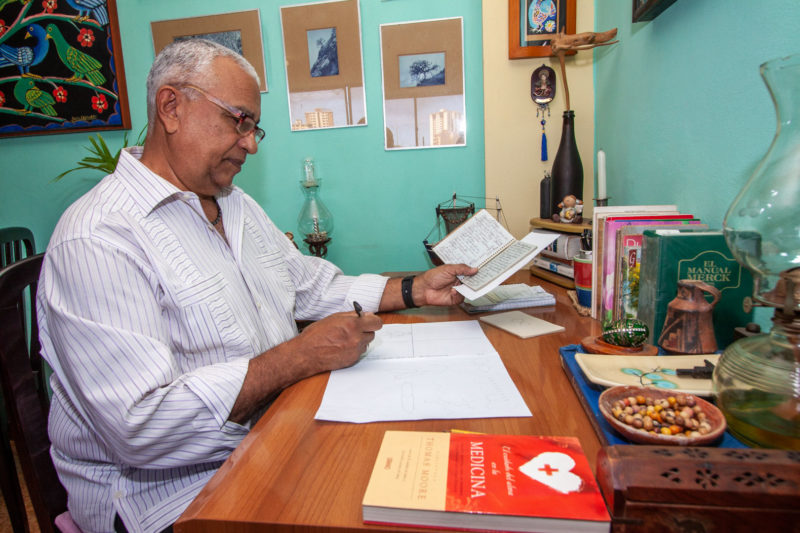

Román González has always been good at remembering moments, details, anecdotes, and images. However, he now takes notes of everything that is being said on the other end of the phone line during sessions, lest something escapes him. The notepad that he is holding is a collection of problems, anxieties, worries, despair, anger, sadness, and grief. That notepad has become the sounding board of the Venezuelan crisis and, perhaps, the logbook for the country’s increasingly deteriorated mental health.

Román listens quietly. He asks questions and suggests different angles to approach issues.

He ends the call after a while and closes his notepad.

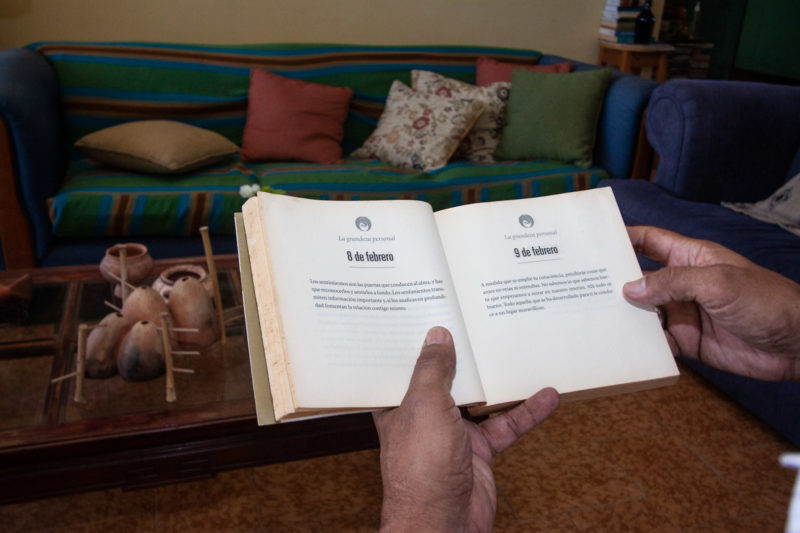

It is a hot January night in 2021. Román gets up from his chair, takes a deep breath, and walks to his room. He chats with his wife Nohemí, then picks up a book and reads a few pages. Reading helps him to put problems —his own and those of others— aside. It is the stories he reads that allow him to have a good night’s sleep.

With the COVID-19 outbreak, the country’s psychological and social burdens were made even heavier. All the feelings associated with uncertainty, such as depression, anguish, anxiety, are now heightened. The Venezuelan Federation of Psychologists launched the Volunteer Psychologists Program to offer emotional support to people who would feel overwhelmed by the new circumstances but who could not afford a private session with a therapist. Public hospitals rarely offer free psychological care and, when they do, the waiting lists are often months long.

And the mind cannot wait.

To be eligible for a volunteer session, the patient must fill out an online form with his/her personal data and the reason for the consultation. That information will be used to determine the urgency of the case and then the individual will be assigned to one of the twelve volunteer psychologists in the program.

Román González is one of them.

Conducting therapy sessions over the phone or through a video call was something new for him, for he had always seen his patients personally at the office he set up at home some time ago.

There was a common thread to the first five cases he was assigned: the patients had suicidal thoughts. They saw in Román someone they could unburden their hearts to. They shared their feelings of loneliness. They talked about the drastic changes they had had to make in their daily routines and habits and about the effects that protracted lockdowns had had on them. They talked about unemployment and massive layoffs, about their fear of getting sick or have a chronic health condition worsened, and about their concern for lacking the means to survive.

It did not surprise him at all.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic had only exacerbated what was already going wrong in Venezuela. Román listens to them attentively. The sessions are aimed at offering containment to patients by suggesting them ways of overcoming, on their own, whatever is unsettling them and helping them manage a given situation, even if the obstacles are still there. Therapy is like a mirror in that it shows people what is it that they can do that they have not yet considered.

Initially, the containment therapy had been planned to last five sessions per patient. But there have been cases where Román has decided to extend it to up to seven because he has come to the realization that some patient needs more assistance and cannot afford private counseling. The cheapest therapy session is USD 10.00, and the minimum monthly wage is approximately USD 2.00.

And he did not want to leave them in the dark.

Lost and, more often than not, alone.

That is what volunteering means to him: to accompany his patients, to reach to them and be part of their journey to finding peace of mind. That is what helping others is all about. And that is something he knew long before the pandemic hit; long before he even became a psychologist.

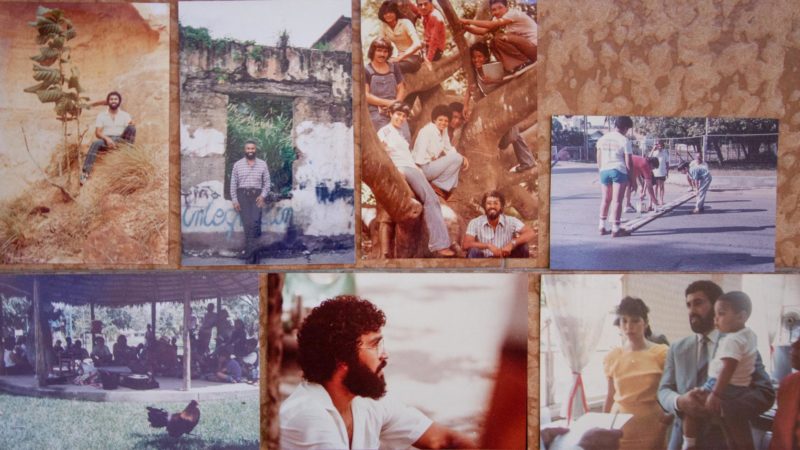

Román grew up on Avenida El Rosario in Los Chorros, a neighborhood in northeastern Caracas, and he saw his mother feed people who had nothing. His house was a place for people to meet, welcome the New Year, and reach out for help.

One day in 1976, rain came down in sheets in Caracas. Time went by and the rain would not stop. All of a sudden, rivers of mud began to bleed from the El Ávila mountain, dragging stones, logs, cars, doors, and people down their path. Many people lost their homes. Román, his siblings and his mother turned their house into a shelter and gave food and refuge to thirty of the victims.

Román was eighteen years old back then. That experience made the desire to help those in need take root in him. And he thought that psychology was the answer. That very same year he began pursuing psychology studies at the Central University of Venezuela. As a student, he was part of volunteer groups and took an interest in crisis and disaster management.

After graduating, he began working as the executive secretary of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs of the Office of the President and specialized in substance abuse prevention. He moved to Anzoátegui some time later for work.

Román was living in San Tomé, a small town located in the southern part of the state, when he watched the Vargas tragedy unfold on TV. It was December of 1999. The images reminded him of what he had lived in Caracas when he was younger.

So he packed a bag and went straight to the airport. There had to be something that he could do. He boarded a plane and landed at the Maracay air base half an hour later, where the people from the Civil Protection team would take him to Maiquetía. What he found when he arrived was destruction, victims, and sadness. So much sadness.

He called the School of Psychology, but nobody answered, so he decided to head to the university. Before moving from Caracas, he and other classmates had made plans to do volunteer work, so he guessed that they would be there, all set, in the face of the tragedy. And he was not wrong. As soon as he got there and saw them, he felt as though they had been waiting for him; as if they knew he was going to show up at any moment.

“Román, you have no idea how much we have been thinking of you!”

He felt like crying, but he restrained himself.

He figured he would be tasked with giving people a bath and changing diapers. He was ready to do whatever task he would be asked to do. But, given his experience, the president and the vice president of the university appointed him coordinator of the shelter at the Caracas University Stadium.

A bus arrived shortly with flood victims.

He helped them settle in and informed them of what they had to offer. The victims needed to eat and shower. And Román knew that they also needed strength, so he took a wad of bills out of his bag, which was what he had been paid at the company where he worked, and asked other volunteers to buy vitamins to distribute them.

As he provided those people with support during such uncertain times, he confirmed to himself that he had made the right choice when he decided to study psychology. He felt he was in the right place, doing what he had to do. And that he would do it again as many times as needed.

Román is the only volunteer psychologist in Anzoátegui. At the beginning, he only assisted patients from that state, because the idea of the Federation of Psychologists was that the specialists would treat people from the place where they lived. But in the neighboring states of Sucre and Monagas there is no association of psychologists, and someone had to deal with the requests for assistance coming from those places.

The Federation proposed Román to take them on. He thought about it, checked his calendar, and accepted. How could he possibly refuse when he knew there is so much need in those states? From that moment on, he had to manage his time rigorously because, in addition to his volunteer work, he also had his private practice, which is his source of income.

Román usually sees twelve patients a day, sometimes more. He tries to schedule his last appointment to end at 7:30 p.m., but some patients will go on at length about their issues or need a little more time, and he lends them an ear.

There are days when it has been an uphill struggle for him, though.

Take what happened to him in mid-November 2020. One day, he woke up and was not in his usual mood. He felt so bad that he thought he had been infected with COVID-19, but he ruled it out after a while because he was not experiencing any of the symptoms of the disease. He was emotionally distressed.

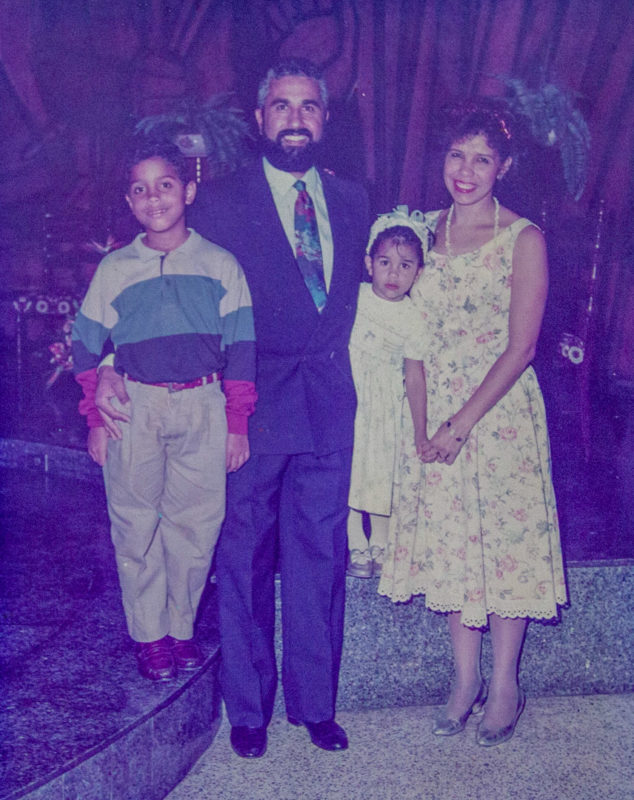

He was thinking of his son, who was in Spain and about to leave for Sweden. He was thinking of his sister, who has cancer. And he was thinking of Romina, his daughter, who had been murdered when she was just four years old in San Tomé in 1994. Her birthday, which is on November 23, was approaching. Many memories of his baby girl came to mind. He missed her, no matter the years that had passed.

Or that other day when he was really down. He called the Federation and asked permission to postpone the two appointments he had for the afternoon. He then contacted the patients and told them that he did not feel well and that they had to reschedule their session.

He spent the afternoon with his wife, watered the plants, and did some reading, and he was feeling much better after dark. He then remembered that the Federation had just assigned him a case, so he decided to call the patient. The phone rang a couple of times before he got an answer.

“Good evening. I am calling on behalf of the Federation of Psychologists. Your case has been assigned to me and I would like to schedule an appointment.”

It was 7:30 at night. At the time when he usually is done with his sessions for the day, Román was talking to a new patient.

Esta historia historia forma parte de La Emergencia Silenciosa, un proyecto editorial desarrollado por la red de narradores de La Vida de Nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

Esta historia historia forma parte de La Emergencia Silenciosa, un proyecto editorial desarrollado por la red de narradores de La Vida de Nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

13405 readings

I am 22 and a current student of the eighth semester of communication and media at the Santa María University in Anzoátegui. I love writing because it’s one of the things that keeps me attuned to reality. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].