Harold Añez and Yerwins Elías were two teenage baseball players who dreamed of becoming major league players. Their families supported them but could not afford to pay for their trip to Colombia, where they had been admitted by an academy that would further sharpen their skills and step up their training. While they raised the funds for the trip, they continued with their drills in Falcón, in central-western Venezuela. Until one fine day their story took another course.

Photography: Gerardo López

Photography: Gerardo López

One mid-June 2018 morning, Harold Añez and Yerwins Elías greeted each other just before heading to the stadium where they would practice as usual. They were inseparable neighbors and friends since childhood. At the age of 16, they had both gone through a long training process as baseball prospects. They had been to several academies in Venezuela, including that of the big leaguer Freddy “El Toco” Galvis, in nearby Punto Fijo. Summer air is very hot in Coro, the capital of the state of Falcón, in the central-western region of the country, which is where they lived. There is a blazing sun and the environment is more humid. That morning, however, the sky was cloudy and there was a cool breeze blowing, maybe as a harbinger of the news that the boys were soon to receive.

After years of constant training, scout visits, promises and invitations, Harold’s father, whose name is Alexander Añez, informed the youngsters that he had finally received the call that they were waiting for. A sports agent had just informed him that the boys had been admitted to an academy in Colombia where, for a few months, they would perfect their technique and then they would have a chance to leave for the Dominican Republic to fight for their long-awaited signing of a contract as prospects.

The agent set just a few conditions. In the case of Harold, who is a 5.9-feet pitcher, he would need to increase his pitching speed from 80 miles per hour to 85 miles per hour; as for Yerwins, who plays catcher, he would need to increase his speed and do some muscle-mass work. There was no doubt about it: they had to continue with their training and prepare for those months in Colombia.

They wanted to become their parents’ pride and joy and that of their neighborhood and of an entire city.

In Venezuela, baseball is the hope of thousands of young people who see the sports as a possibility to transform their lives. News are frequently published in the media about young prospects signed by U.S. teams under contracts worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. That one of their own could become a big leaguer is the dream of many a family, regardless of the social condition.

But as with many paths in life, the one to baseball is not an easy one to travel. It doesn’t just require talent: it takes perseverance, dedication, discipline, some luck, and financial support to keep up with the training regimen, which includes special nutrition, vitamins, clothing and coaching.

Harold and Yerwins met the athletic conditions, but they lacked the money to travel and settle in Colombia. The academy that would receive them offered them the places and training as part of a scholarship, but they needed to pay for the travel expenses. It was money their families didn’t have. Harold’s parents worked as laborers at the Francisco de Miranda University, while Yerwins’ father was a blacksmith and his mother was an administrative assistant at the office of the governor of the state of Falcón. They are hard-working people living with a dwindling income in a country with a hyperinflationary economy.

Months passed and they had not managed to raise the funds for the trip. No state institution offered them support. In October, in an effort to helping the kids, Williams Elías, Yerwins’ father, who had a blacksmith’s shop that had been severely affected by the economic crisis, decided to emigrate to Colombia, where he would work in his trade and hopefully send some money home to support the family and, needless to say, to pay for his son’s project.

In the meantime, the teenagers went ahead with their baseball training. They took it very seriously, so much so that, even though they were good students, they quit high school as early as into their third year to dedicate themselves exclusively to their training.

It had been months since the day they received that promising call from the sports agent, during which time they remained immersed in their training routines while trying to gather the money they needed. There came December, and the kids had not been able to leave for Colombia. Harold was the only boy of Alexander’s three children. Yerwins was an only child. They felt that they had an increased responsibility to their parents, and were grateful for all the efforts that they were making to support them.

Yerwins talked to his mother about the possibility of him leaving all behind and move to Colombia, just as his father did.

“Absolutely not,” she replied. “You keep up with your baseball”.

At noon on December 1, Harold and Yerwins left their homes in the Cástulo Mármol Ferrer slum, just 100 meters from Avenida Roosevelt in Coro. They carried their packed lunches and a debit card with a balance of 500 bolívares, which was the property of Alexander, to pay for a time-slot in the swimming pool where they make drills as part of their arm-strengthening routine. Then they would walk back home, which is what they usually did either because they didn’t have bills to pay for the fare or because it saved them some money. That was just one more day of training. They should be back at 6:00 p.m.

Yes, at 6:00 p.m. they were supposed to be back.

But it was 6:00 in the evening and they had not returned. Then it was 7:00, and then 8:00, and there was no sign of the boys. By 9:00 p.m., Alexander began to worry. Harold, his son, wouldn’t answer his phone. And it was not like him, because he always picked up.

He could feel that there was something wrong going on.

With that hunch pounding inside, he left for the headquarters of the Scientific, Criminal and Forensic Investigations Corps (CICPC, by its Spanish acronym), which was located near his house. He wanted to rule out the possibility that, for some reason, his son might have been detained, as was often the case with young people in that sector.

He asked for them upon his arrival.

“They are not here,” they replied.

Then he went to the Falcón police, about 100 meters from the CICPC, and from there to the general hospital. He got the same answer.

Yenni, Yerwins’ mother, followed suit. Her son didn’t respond to her messages. Nothing. No one knew a thing about the boys.

Alexander and Yenni came back with no answers to their questions. Not a single soul could fall asleep that night at the Añez’s and the Elias’s.

It was at 3:00 a.m. when a neighbor that had learned of their search got a text message. “A couple of chamos arrived in the general hospital with gunshots; apparently they are from Cástulo Marmol.” She ran. She read it. Alexander felt terrified as he listened to her words.

Immediately, and without much thought, he left for the morgue of the healthcare center.

He was shaking when he arrived there, but he managed to cross the door as he could and got in.

He could not believe his eyes: lying on a stretcher, with two gunshots to his chest, there was his dear boy.

He jumped over his son’s body, crying, screaming. What had happened? How was that possible? And, amid the confusion, he demanded to know where his son’s best friend was.

“Find Yerwins! They must have thrown him around, like a dog!” he said, repeatedly.

And indeed, a few meters from the stretcher where his son was lying, there was Yerwin’s corpse, lying under another person’s body.

Yenni arrived at the site a while later, asking for her son.

“Come on in and take your crook with you,” they told her as soon as she peered into the doorway.

Yerwins’ father learned about it all on a bus on his way to Ecuador, where he had decided to move from Colombia to see if he could fare better. He immediately changed directions and took the long way back home by land from the Colombia-Ecuador border to Coro, feeling that he was living a nightmare.

The CICPC’s version was that the boys, in the company of another youngster named Randy, were robbing a fruit shop in the east of the city when the police took them by surprise and a confrontation ensued. That was also the version echoed by Oswaldo Rodríguez, the commander of the Citizen Security division in the state of Falcón and an infamous cop who went by the alias “El León.”

“El León” had a bad reputation. He had been in jail. On March 10, 2003, during Rodríguez’s time as chief of the police of the state of Falcón, a man named José Antonio Vargas came to the general command center to bring food to an inmate, and he was never heard from again. “El León” was elected mayor of Coro for the 2008-2013 term, but he could not finish his tenure of office because he was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment in 2011 for Vargas’ disappearance. He ended up serving only three.

No one believed the story that both the CICPC and “El León” kept repeating. Faced with the people’s commotion over what had happened to Harold and Yerwins, the police argued that witnesses saw them getting in a burgundy Aveo on Avenida Roosevelt, along with two other men; they claimed to have security camera videos where they were seen getting out of the car at the fruit store and that they had been recognized post mortem by the robbery’s victims.

Everything seems to suggest that the boys were indeed involved. What no one can explain is what might have led them to do so if they had such a promising future ahead. The fact is that, as soon as the investigations were launched, it was revealed that Enyerber Torres Mendoza, also a member of the CICPC with criminal records, was the mastermind of the robbery. According to witnesses, he took the boys and Randy Rojas to commit the crime. And he was one of the first officers to arrive at the scene to confront the boys, having realized that he had been exposed.

Enyerber Torres is currently doing jail time on charges of aggravated robbery, criminal association and use of teenagers to commit crimes, while the other officers involved in the procedure are free.

Harold and Yerwins’ relatives still fail to understand how it is that both boys died the same way: of gunshots to the chest. The pants that they were wearing were heavily soiled at the knees. That’s why they think that they were killed.

That they were killed in cold blood.

Carrying folders full of newspaper clippings and police reports, they keep asking the same questions to themselves: How could two young boys with no criminal records and who had never used a weapon be involved in a robbery? How? Nor can they understand how, if it was a clash with the police and the shop was closed and the thieves were inside and the officers were outside, the police managed to shoot them precisely in the chest and leave them otherwise unscratched.

They know it’s not the first time that something like this has happened. The Diario Nuevo Día keeps its own statistics according to which there were 103 deaths in “clashes with the police” in 2018. In April 2019 alone, 14 people were reported dead in Falcón because they resisted the authority.

Aware as they are now that stories such as theirs repeat time and again but with different names, they have met with the Committee of the Families of Victims (COFAVIC by its Spanish acronym) and other human rights groups. Their only purpose in life is to clear their children’s names. They don’t cease to insist, even if some officials have “recommended” that they leave things as they are and that they do not mess with “El León” because “you know how he is.”

Five months have passed. The teenagers’ parents remember their funeral, which neighbors, friends and people from the city attended in solidarity. They also recall that they were humiliated by the ill-reputed policeman at their children’s wake service. They say that “El León” ordered pictures to be uploaded on social media of a wake where there were weapons on the coffins, maybe seeking to justify the murder of the two sportsmen in the public’s opinion.

But they will repeat it as many times as necessary: all which those coffins had inside were bats, baseballs and uniforms.

In the days following the funeral, at a meeting of the Caracas and Magallanes baseball teams in Valencia, “El Pelón” Luis Dorante, who is a native of Coro and the manager of the Magallanes, requested a minute of silence to honor the boys.

Yenni cries as soon as he starts talking about her son.

“He would give me no troubles. He spent the day playing, training, watching baseball videos.”

Wiliams tries to calm her down.

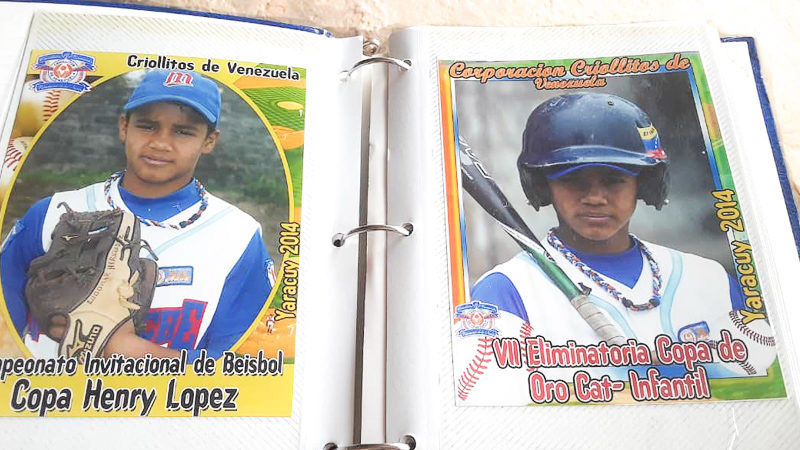

On an altar in their living room, they remember their son with the photos of him that they began to take back when he played in the children’s categories of the Criollitos de Venezuela. There is also an image of Jesus Christ, because they have never lost faith. And there are trophies, bats, baseballs and a cap that reads ‘Falcón’, the state that he represented on several occasions.

Harold’s room, which remains practically untouched, houses the ‘best-pitcher’ trophies and medals that he won in various tournaments, as well as his training weights, an Arizona Diamondbacks practice manual, and posters of his idol, Dominican big leaguer Emilio Marte. There is a photo behind the door that was given to him by Falconian baseball player Maglio Ordoñez.

And downstairs, in a drawer, as if it were a hidden treasure, there are four pairs of old sneakers, all lined up, that Harold had decided not to throw or give away. He used to tell his dad that he needed to keep them because when he got to the Major Leagues he had to remember the steps that he had taken and the path that had brought him there.

Traslation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

1753 readings

I am a college professor, a human rights defender and a social activist. I believe in freedom, solidarity and education as a formula to pull through. “Do not proclaim the freedom to fly, but give wings; not to think, but to give thought.” Unamuno.

2 Comentario sobre “He Wanted to Remember the Steps That He Had Taken”