A kid who feels singled out because he is different. A kid who prefers to hang out with adults and who loves to read books and listen to the radio. A kid who is hypersensitive to many things around him. A kid who is labeled as a smarty-pants and whose behavior is considered as imprudent. Following a late diagnosis, surgeon Björn Martíinez delves into his memories to piece together the puzzle that is his own world.

Sunday mornings have a natural charm, perhaps because we know there is usually no school or work and we feel free. A glimmer of sunlight, a clear blue sky, some wind that is not cold but gently refreshing, and the smell of mom’s arepas on the skillet are the first things that come to me when I wake up. After breakfast, they get me dressed and, like every Sunday morning, we go to church, just a few blocks from home.

It is an already familiar scene that I have learned through routine.

I sit between my parents and I know that I must stay still and keep my voice low, even if I really don’t want to. I look at each person around me: their faces, their clothes and their gestures. Why does that man have that expression on his face? Why does that grandma look so tired?

Pablo, whom everyone calls Father, finally makes his entrance. Occasionally, he goes to my place and listens with my dad to some of the records in his collection over a drink, or joins us for a meal.

It strikes me that at one point during mass everyone stands in line, including my mom and dad. They ask me to stay put and wait for them, so I do. But it puzzles me. What are they getting in line for? I give it a thought and, once the line has cleared, and with my parents unable to stop me, I get up and go to where Pablo is.

I stare at him but he can’t see me. No wonder he can’t: I’m a 3-year-old miniature of a human being. So I decide to pull on his cassock. He thinks I’m saying hello, but I’m not, I’ve said hello enough. What want is that which he has given to everyone else.

They all look at me and laugh. People are amused by some of the things children do, and this is one of them. My dad calls me from near the church’s podium, in an effort to prevent me from going all the way up, but I pay no attention to him. Someone is heard saying “I’m sure he wants to take communion,” which gets a lot of laughs. But that person is right. That’s what I want and, surprisingly, Pablo ignores that parishioner’s comment and gives me a Host.

I liked it. From that first time on, every time we went to mass I would do the same thing: I would pull Pablo’s cassock for him to give me a Host. It became quite a show that everyone seemed to enjoy.

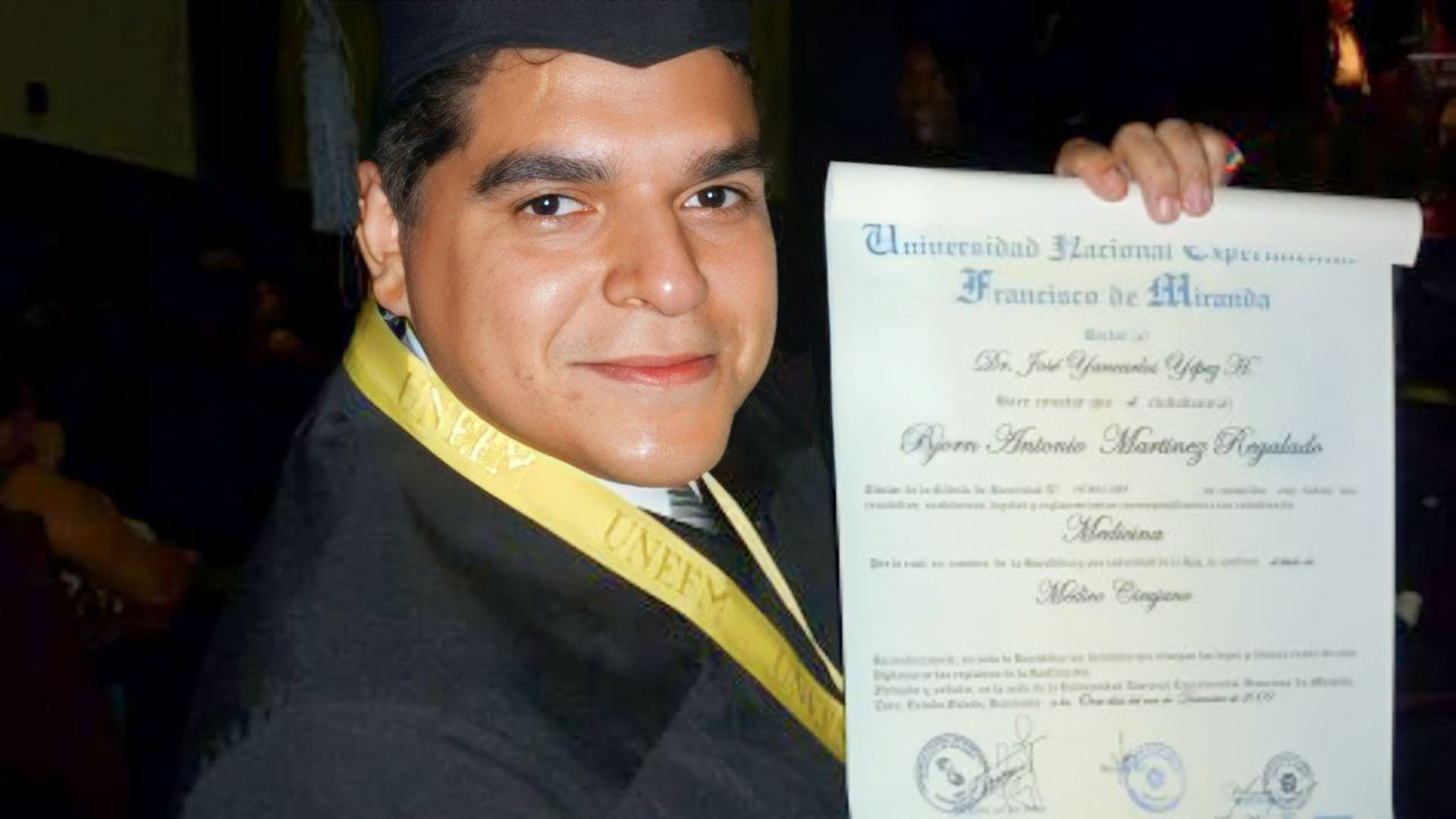

I played like any other child. However, I spent a lot of time alone just because I wanted to and, when I was older, because my parents had to go to work. During that time, I watched television, but mostly I read. My dad has always had an interesting home library. And I also read pieces of paper, notes, and documents he kept. No one had the slightest idea about how many things I got to read. What else can you expect from a child who reads anything and has so much to explore home alone?

Between school years, I used to go to a summer camp in a national park nearby. I learned a lot there and met great people whom I still call friends. But there were things that I didn’t want to do, like those involving physical contact or getting dirty. No matter how much they asked as they were playing games, I would step aside. I thought about my clothes, almost all white, and I didn’t want them covered with soil. Some of my fellow campers didn’t like it, and neither did the camp counselors. And, from time to time when I spoke, the other children didn’t understand much of what I said, and the grown-ups would tell me that I was entirely off-topic.

I go back to my childhood and I remember it all clearly. It is a strange feeling. I talk about what I read or about what I think. And every so often I warn people about what’s going to happen to them if they do what they’re doing, and they don’t like it. As I grow up, I am told that I need not be such a show-off, that it’s not okay to play the wise guy. I know the words, but I really don’t why they think they apply to me. I honestly believe that we are all the same. It’s just that if I see someone doing something that I know isn’t right, I consider it appropriate to help them by warning them against it.

I absolutely love music. My dad has a huge amount of LPs, which are vinyl records of about 12 inches in diameter. Although the record player is sort of a sacred possession, they just taught me how to use it. So, when I’m alone in the house, I get to enjoy all that music.

I’m older now. I’m nine. At school, I’m part of the traffic safety team, of the Bolivarian Society and of the Science Club. They enrolled me in a course called Catechesis, which prepares you for your First Holy Communion. I have lessons every Saturday morning. For me, it’s more like a review because everything they tell me there I already know.

“There are Ten Commandments: the first two are about God; the third one is on the feast days; the fourth one deals with parents…,” I hear. But I immediately think that’s not true. The Third Commandment is about God’s name and the Fourth is about the Sabbath, which is why Jews do not work on Saturdays. There are Jewish things we do at home. I found out why later on, but that’s another story. The point is that I raise my hand and talk about what I know about the Ten Commandments. The catechist tells me that I am mistaken and that what she is saying is the way it is in the Bible, but I tell her that the information is inaccurate.

“It is in the Catholic Bible, but there are several bibles,” I explain. “In fact, the original version of the Bible is that of the Jews, and even the Protestants have it that way. What happens is that, a long time ago, a pope decided that they could adapt the Bible and they made one of their own.”

“Well, then, we must do as the Pope says,” the catechist replied.

“It depends on who you want to listen to, because if the Bible came directly from God, as you said, no human can change what God did; they always say that at mass…”

I fail to see the usual expression of sympathy in her face. There is utter silence and they change the subject. I sit down again and ask myself why she didn’t like what I said if it is something that is in the books. I did not make it up. It is there in black and white for everyone to see.

I will take my First Holy Communion all the same. I have to use some items my dad keeps in a box: a large candle, a golden arm band and a big cross made of gold and pearls, and that just for some pictures. Truth be told, I find that uncomfortable. I have so much fun when I see Pablo, the priest, and I tell him, referring to the communion thing:

“This is not my first time, you know. That happened a long time ago.”

We both laugh.

“It just so happens that you are special, tiger,” he says.

Sometimes, Pablo calls me ‘tiger.’

My grandmother gives me a small battery-operated radio as a present “So you can always listen to music.” It’s yellow. I find the color a bit bright; I wouldn’t choose it, really, but I thank her anyway. I’ve already learned that, if I don’t want the expression on people faces to change when I talk, it’s best to say what they expect to hear or what others say in similar situations. Which means I have to think carefully about my options before I answer. But that is not always the case, though. Sometimes I still rub people up the wrong way.

The radio has a black strap that allows me to hang it on the window handle when I do my homework at the table or on the desk chair my dad bought me. The chair desk is green, foldable, and very practical; it feels like being at school, and I like it.

I also listen to the radio at night. I sleep on the bottom of a bunk bed, while one of my brothers sleeps on top. In the late hours, when I am supposed to be sleeping, I pick up a station with someone who talks a lot and gives his opinion and asks others to call in to give their opinion too. I don’t know if I can call in being a kid, so I just enjoy listening to him.

I also listen to a program called Reencuentro de medianoche [Midnight Reunion], hosted by a lady named Isa Dobles. Her voice sounds warm to me and sometimes she makes comments like mine. I liked her right away.

That program I did dare call a few days later.

It is the middle of the night. All the house’s lights are off. I get out of bed very quietly because I don’t want noise to be heard upstairs, and I leave the room with utmost care. Tiptoeing has always been very easy for me, even fun. I get to the living room and grab the phone. There’s tone. I put my finger on the rotary dial and dial seven digits I had in my head. I hide behind the curtain next to the phone, thinking that I’ll be less visible that way. I say good night and in a matter of minutes I’m on the air. I say hello and my voice is heard on the radio. It’s wonderful. Mrs. Isa greets me and listens to what I have to say. It is something about being good people and taking care of the environment. As soon as I finish, she asks me:

“Hey! How old are you?”

Oh, oh! I get all chucked up and say:

“I just turned 10”.

“TEN? And don’t you think you should be asleep by now, kiddo?”

“Well, according to my parents I should, but I’m not sleepy. I am a night owl. Everybody is sleeping here and I love the radio, so I listen to it at night. And a few weeks ago I found your program and I liked the way you talk. And today I wanted to say something that I consider important.

“Ok,” she said, “it was a very nice thing to say, but you must have permission to be up at this hour and use the phone”.

“You are right. Thank you. I love your program. Have a nice evening.”

But I never really asked for permission. I kept listening to her and calling whenever I could. I also dared to call other programs. They even told me that they thought it was very sweet of me to call, and that I was very mature for my age. People even asked for me and would send me their regards.

One day, when I was visiting my mother at work, a couple of Cuban sisters who worked with her said:

“Hey, kid! You are the one who calls Isa’s programs! We heard you last night and we said to ourselves that of course it was you. It’s obvious that Isa likes when you call. She always speaks very fondly of you and says she wishes there were more children like you. You even have your fans on the show.”

I lost my face when I realized I had been caught. It didn’t occur to me that someone who knew me could hear me talking on the program and recognize me. My mother was at a loss for words, clearly in shock. One of the sisters said:

“Girl, what a speaker you have home. That boy has it all figured out!”

My mom just looked in my direction and told me that we would talk later, but neither her nor my dad ever brought up the subject.

I continued to listen to radio programs and became a permanent guest on one that the Radio Caracas Radio production team broadcasted every afternoon. After a lot of pleading for permission, they let me go to the station. I was 12 years old. I knew which buses to take and how to get there.

I arrived at the reception desk and announced myself. They looked at me from head to toe and summoned the person who was going to meet me. Down the stairs came a white, round-faced, smiling woman with big black hair. Her name was Rosa and I couldn’t believe my luck when she greeted me. I was on the radio and a model was assisting me.

We headed to an office upstairs. I met Marie, another slim white woman with light-colored lively eyes and beautiful blonde hair. She had a pretty smile and greeted me warmly. I also met Yuly, a dark-haired, thin woman with black hair. I was awestruck because I didn’t know models worked at radio stations. Right at the back of the office, in a separate room, there was a tall man with glasses. He sported a ponytail and had a very serious-looking face. It was Víctor, the boss.

Arriving at his office was like going to Mount Olympus, so everyone approached him with great tact. He saw me and welcomed me.

“Tell him how to behave himself,” he ordered, and he stood up and left.

“Don’t you worry. It is how he is,” Rosa said, putting her hand on my shoulder. “Let’s go downstairs. It’s time!”

And off we went to the radio booth. It was like a dream to be there. It was the place from where I listened to these people on my yellow battery-operated radio at home. And now I was there.

They all remained friends with me. I don’t know exactly why, but I’ve always found it much easier to socialize with adults. We can talk about everything… Well, I guess not everything, for I know there are things they don’t talk about with me or in my presence. But my closest friends are adults, with the exception of some buddies at school and in the summer camp.

Adults get me better, though not all of them. Some tell me I talk too much, or that I talk about or say things I shouldn’t. They say I should be playing. But I get bored easily. I’d better read or play things on my mind, where I can create worlds or see what I read as if it were a movie.

There are people who look at me with affection, but most look like they don’t understand me or that they don’t like me for some reason. I can’t wrap my head around it. I’m just a kid and I don’t think I’m doing anything wrong. Still, it happens. Sometimes I don’t feel accepted even at home.

Have you ever wondered what it means to have to pretend to be someone entirely different just to make other people, even your family, feel good about you?

Consider for a second that you love silence and that you are altered and hurt by many of the sounds around you. Imagine for a second that the way your brain works is not the same as everyone else’s. It’s like in Computer Science: what we do in Windows is not the same as what we do in Linux; we arrive at the same result, but in different ways, at different times, and through different images.

What was the first thing you did today when you woke up? Maybe you picked up your phone, or perhaps you turned on the TV, or just went for a shower or to the window to have a smoke. We all do different things, right? So, why should anyone’s difference catch your attention?

Our world is a maelstrom of stimuli that can be harmful to some. Yes, harmful. It’s not just a matter of preferences. Think what you would do if the voice of someone you love made you uncomfortable, or if the touch of that person on your skin annoyed you. And you don’t know why, but that’s how you feel. You just can’t change it. You have no way to feel any different. There is no pill you can take that will fix it and you are not this way by choice.

A simple color, texture or smell can affect a body to the point of paralyzing it, disconnecting it or, even worse, making it burst in an instant. Why? We don’t know. Now imagine it’s you and for a minute think about how you would feel if something like this happened to you, if you didn’t know why, if everyone around you looked different and not even you can understand what’s going on. And if that were not enough, imagine that everyone around you seems to be upset, uncomfortable or annoyed with you, with your differences, with what’s happening to you.

You are that pebble in their shoe.

Something needs to be done! But what?

What if I act the same as everyone else and just dismiss what this mind of mine that is too sensitive to so many stimuli says? Can it be done?

Yes, it can!

But it comes at a price, like everything else.

All the effects of the things around you stay with you and will continue to upset you and hurt you, but you will smile, pretending to be the same as everyone else and trying to live like everyone else, even if it means repressing yourself. Even if sometimes you just go off, like a pressure cooker, because of the unbearable stress…

Welcome to my world!

Did you read about the 3-year-old boy who pulled a priest’s cassock asking for a Host? Or about the 9-year-old boy discussing the economic situation of a country with a 25-year-old person? Better yet, did you read about the 10-year-old boy who listened to the radio at midnight and participated by phone in the very same program he used to listen to? Or about the 11-year-old boy who read himself to sleep with the book 4 Crímenes, 4 Poderes?

“What a witty boy!” “He is too old for his age” “Here comes your pain in the neck” “What a show-off! “There’s the know-it-all.”

No. Nothing could be further from the truth. That kid did not choose to think that way, much less act that way. He himself did not know or understand why he was different. No one knew what happened to him and, needless to say, no one helped him to understand himself, to feel better about himself or, at least, to be able to express himself.

Today, 30 years later, I am figuring out what this is all about… at long last.

Well, that’s what I am trying to do.

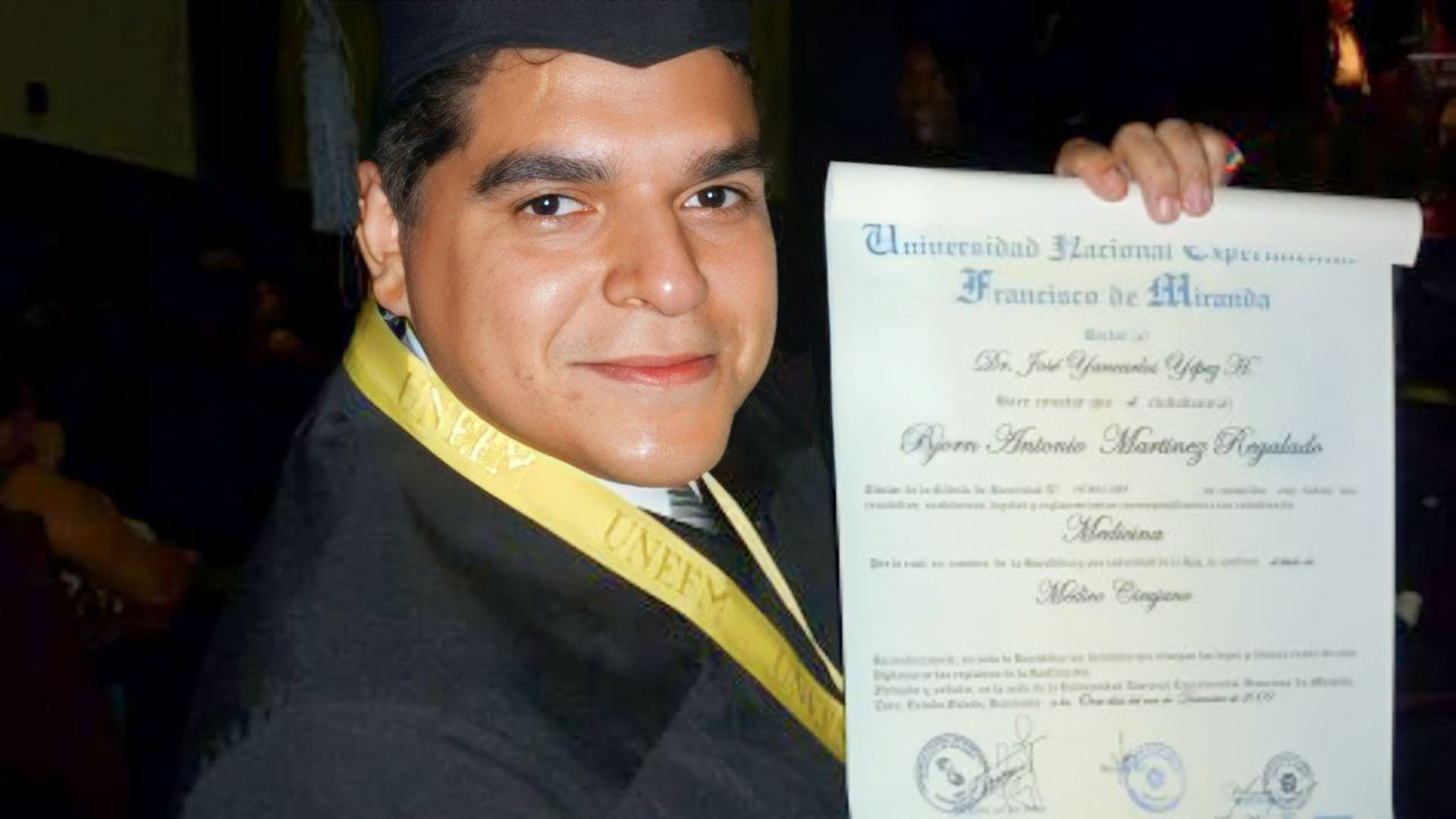

I am 42 years old. One year ago I was diagnosed with Level 1 Autism Spectrum Disorder, previously known as Asperger’s syndrome. I am a medical surgeon, with graduate studies and training in various areas.

And now I know the answer to so many things, the ones I have told you about and the ones I have yet to tell.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

1163 readings

I was born in Caracas on a 14th of July. I was named after a famous tennis player. I graduated as a medical doctor and I have been practicing as such for a long time now. Writing has always kept me company. I do research, I offer counsel and I help whenever I can. Cogito Ergo Sum.