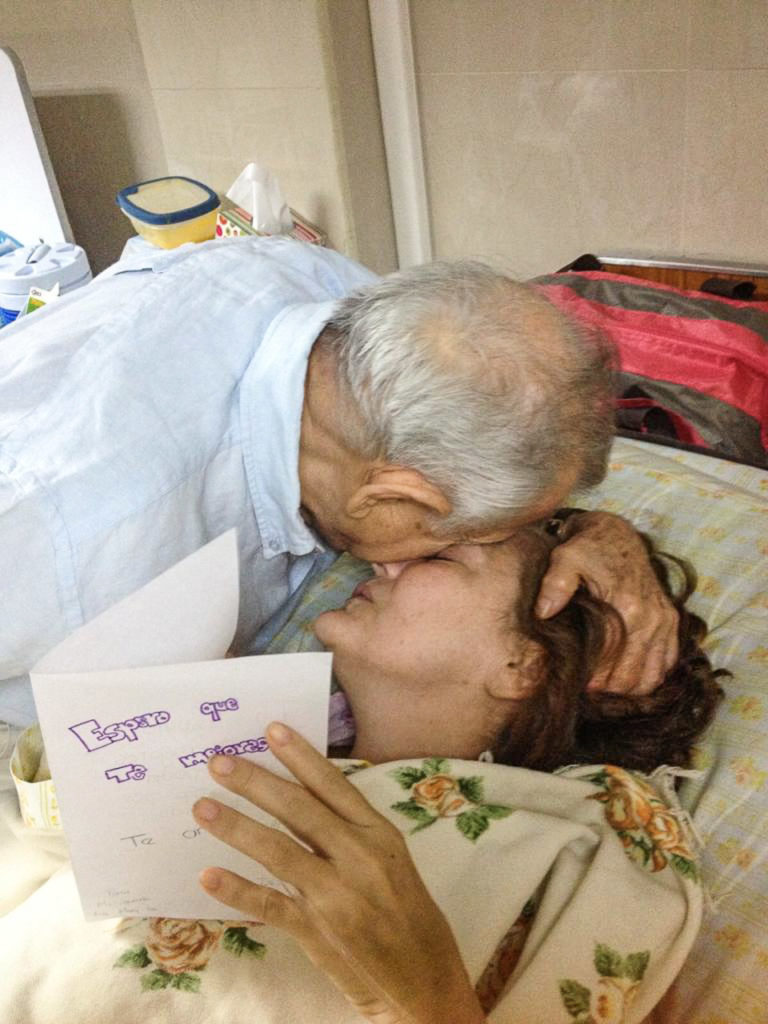

A granddaughter who dreams of her. An illusion that prolongs life. Mary Lía Aristimuño died of blood cancer at the Manuel Núñez Tovar Hospital in Maturín. It happened one day in 2016, at a time when the healthcare center was already facing major shortages. Her sister Liamir was by her side during the most difficult hours. This is her testimony, as she tries to put in order her memories and their hidden meaning.

Photos: Family album.

Photos: Family album.

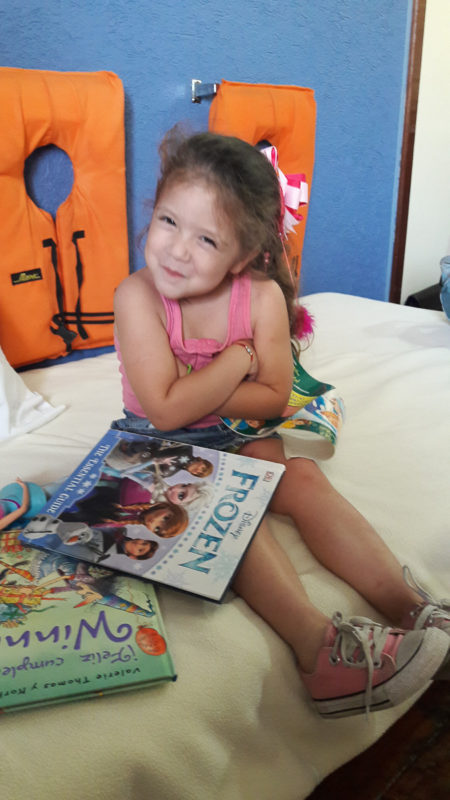

Fabiana talks to her since she was 3 years old.

“Mom, I’m happy. Mamaíta came and hugged me.”

Although she could not possibly have memories of her, she always says that she sees Mamaíta, as she calls Mary Lía, my older sister, and that she talks to her.

In his anecdotes, Dad always portrayed the progressive Maturín of the 1950s; that city where the Aristimuño family, my family, owned the hotel where travellers stayed and the Christ of the Holy Sepulcher that they lent for the procession of the Holy Week. It was a prosperous family with solid foundations.

“Dad didn’t let me go to Caracas,” Mary Lía once commented, unreproachingly and with a smile.

That’s why she didn’t go to medical school, which had been her wish in the first place. Instead, she stayed in Maturín, the capital of the state of Monagas, where all she could do was take some courses that would allow her to work as a secretary. That was enough to lead a quiet life, buy her blue Ford Zephyr, have fun and try to make a home. She married once. She got divorced. She had a white Pekingese dog with black spots. The pet’s name was, needless to say, Domino.

She had a relaxed way of looking at life and, although she was stricken with difficulties time and again during her adult years, she always smiled. She was kind and cheerful and playful and loved to joke around. She loved selflessly. Her tiny body was overflowing with sweetness. That body which survived a terrifying road accident.

The one that sustained her for 64 years.

Maturity made her life simpler. She needed a lot, but she asked for nothing. The country placed great demands on her, and she accepted her “destiny” naturally. She did not whine. If a small complaint ever escaped her, she would immediately conceal it with some humorous remark.

Going on 40, and with no intention of forming a family, she decided to have Mariolim, her only daughter, the fruit of a relationship that did not live up to her expectations. From then on, Mary Lía would not be alone anymore. She devoted herself body and soul to raising her daughter, until their roles reversed. And yes, she was her companion until her very last day.

By mid-August of 2012, with a Venezuela in decline and a collapsing healthcare system, Mary Lía was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer that originates in the bone marrow. Later on, a leukemia diagnosis would add to the list.

Like any citizen of the disappeared upper-middle class, she now depended on the diminished public health system; she, a proud Aristimuño. To get sick, in this context, was almost a death foretold. A disgrace.

Medical consultations became a daily occurrence. Visits to the laboratories were part of her weekly routine: sampling, biopsies, and the constant waiting for a result that would portend some hope. But that was never the case. The prognosis was very close to silence in those smiles.

However, her cheerful spirit would not give up on illusion.

I accompanied her only a couple of days during her first stay in the cold and dark José María Vargas ambulatory in Maturín, where she was surrounded by seven other beds for an entire month. Her daughter Mariolim, my other sister Gilmir, her twin neighbors and me washed her, shaved her, combed her hair and hugged her. It was already becoming customary for family members to be the ones who cleaned their sick relatives and provided them with medications, supplies, food, everything.

“If you are going to stay with the lady, remember not to bring any valuable object and to close the door,” commented one of the nurses.

How to fall sleep after such warning?

It was the foretaste of the long nights that I had to sit on a plastic chair next to her hospital bed, which was dressed in sheets that we had brought from home. For her, conversations led to sleep. As for me, I could barely manage to close my eyes for a few seconds.

This is how the days went by since her diagnosis, and our frustration after our tour of the pharmacies added to the drama: we could not find the full round of treatment. Now illnesses go hand in hand with empty pharmacies and attempts to find with relatives in exile what we cannot find here.

In December of 2012, she was assigned one of the rooms of the Manuel Núñez Tovar Hospital in Maturín. Two beds. One bathroom. A stench of abandonment, of floor-cloth soaked in dirty water, of dust, of hopelessness.

Once again, we washed her, shaved her, combed her hair, hugged her.

I also spent a couple of nights there. But we had been granted a privilege: it was just the two of us. This time I also trimmed her fingernails, cleaned her ears and changed her diaper more than once. Those two nights were again long… very long.

And as we reminisced of the happy times when we were young, we made fun of all of it: of the bathroom full of green mold that resisted the chlorine that we brought from home to clean in, of the soda containers that had been cut in half to collect the drops of water coming out of the rusty tube where there was once a shower, of us feeling like queens because that room with its wet walls and its peeling paint was just for us to stay. Just for us… and for the head lice that she got in that place.

“At night, lock the door and place something heavy behind the door. No doctor will come after 8:00 p.m., so don’t open it to anyone.”

That nurse’s warning on a Christmas Eve kept me awake. And, indeed, it was 11:00 p.m. when someone tried to open the door. We never knew who it was.

The next morning we woke up singing the chorus of a song that Ivo, a famous singer from the 1970s and an admirer of hers from her younger days, wrote for her: “Mary Lía, Mary Lía, I love you. Mary Lía, Mary Lía, I adore you.”

With the new year, “Yiyi”, as we called her, returned home from the hospital. She was discharged even though she was getting worse. She continued to lose weight. She was deteriorating, rapidly. Her whole body hurt and she could not stand on her own feet. Getting her out of bed was an excruciating task. However, as frail as she was, she was constantly joking. She always laughed, even when in pain, even at herself.

“Hold me, girl, for I could break into pieces,” she said, while tickling my legs. “And if I do, how on earth are you going to pick me up and glue me back together?”

She laughed, but she was resigned.

And in the middle of it all, there was life peeking through: it was Fabiana. Little did she know that Fabiana would come to prolong her life just when it seemed to be slowly fading away. A sudden burst of energy took hold of her: she was going to be a grandmother. Mariolim was pregnant.

So, she went to the traumatology specialist. She had her tests repeated. She went through physiotherapy sessions. She had a new reason.

“Hey, girl. Get up! Do you think that you are going to starve my granddaughter this early? Mario, get up. Breakfast is on the table!”

Mariolim couldn’t believe it. That weekend, Mary Lía got up and cooked rice, plantains, a salad and fried hake.

She managed to walk again without a walker two months before Fabiana was born. She tried to be her old self again. She said that she needed to heal to take care of her granddaughter. And heal she did. She ran. She literarily ran to meet Fabiana the day she was born. She took care of her ever since that day. She slept next to her. She nursed the baby’s umbilical stump. She gave the baby her first bottles. She taught the baby to walk, to eat, to shower, to push the little stool to climb into her bed. Fabiana seemed to understand that Mamaíta could not pick her up.

But in 2016, we had to live through the agony of farewell, again. This time it was hers. Dad had passed away a year earlier. He was gone after an entire day trying to get him admitted into an intensive therapy unit north of the state of Anzoátegui, but there were no beds available; he then spent six days in a private clinic, which the family helped pay for. And then he spent fourteen days at home, terminal. The routine of taking care of him went from looking for oxygen and diapers to looking for his medication, which was nowhere to be found.

Mary Lía relapsed. She spent one day in a clinic; a couple more days in the hospital, where there was nothing they could do for her anymore. She spent five days at the Maturín Medical Center, where she was ran more tests. She spent four days at home. A couple more nights together. She had trouble breathing. She was not smiling that constantly.

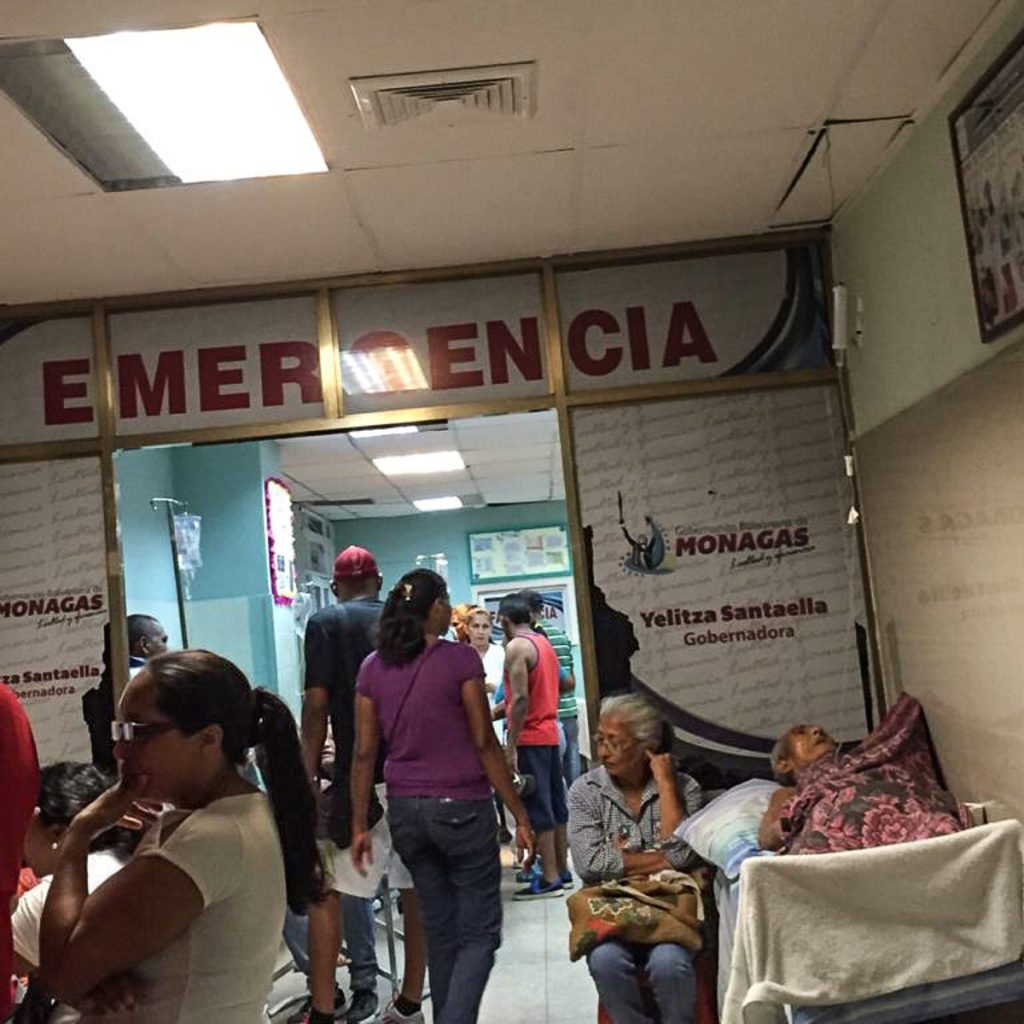

We went back to the hospital; however, this time there was no room for her, no privileges. No more queens laughing at the mold in the bathroom. The shock-trauma unit of the Manuel Núñez Tovar Hospital was packed with people. There were maybe ten half-mended hospital beds clustered together. Six stretchers with virtually no room to walk between them. Bed sheets featuring colorful flowers, stripes, plaids, cartoon characters. The stench of floor-cloth soaked in dirty water was there again, compounded with that of blood, sweat, saliva and food.

Ropes and juice containers balanced the plastered limbs of a couple of patients. Although only two companions were allowed in per patient, anyone who wanted to get in or out could easily do so. It looked like a Sunday street market. It was all so confusing. There was as much noise as small cockroaches.

I got scared when some wounded prisoners arrived with their families. There was no door to close. No warning from a nurse. I was afraid that something worse would happen, as if it could get worse than that.

Mary Lía was placed on a stretcher where she could barely fit, despite her low weight. To move the stretcher was to stumble upon the companion of the patient next to us; it was to touch something you didn’t want to touch; it was to yearn for the good times of that prosperous family, the Aristimuño family.

We were hoping that she would be administered the platelets that Mariolim had managed to find. Mary Lía’s blood count was bottom low. We hoped that she would resist so that she could start a new round of chemotherapy as scheduled. We hoped that every effort would be made, because that’s what doctors are for.

Suddenly, Yiyi began to bleed from her nose. She was also bleeding through her mouth. I lifted her head with my right hand and tried to clear her airway. The rest of the family came in and out of the place, like everyone else. But nobody would take me out of there. I was using gauze and cotton in huge amounts, which I threw in a bag tied to the legs of the stretcher.

Mariolim came back in. She stood on her right side, stroking her hair. I stood on her left side. She thought that she was getting better as she tried to breathe. I looked at her and she understood she wasn’t.

“Can you help me?!” I implored the doctors.

The resident’s answer brought us back to reality. Mary Lía was dying amid that chaos and the indifference of those who swore to save lives. She was dying surrounded by strangers who understood that scene better than we did. So, I followed the orders from the young woman in the white robe: I cleaned up the blood and waited.

Mariolim leaned over her chest. She cried. When Mary Lía’s heart stopped beating, I cried with her.

Juan Carlos, the youngest sibling, was tasked with taking her to the morgue and providing her identification data. I thought that was a task for the man in the family. But I was wrong, for it is no one’s job to walk among naked corpses all piled up on the floor.

Today, at age 5, Fabiana still talks to her.

“Mom, I’m happy! Mamaíta came and hugged me. She told me that she will take care of me so that nothing bad ever happens to me. She was the one who loved me the most.”

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

2171 readings

I learned about journalism in the newsrooms where my father used to take me. He also instilled on me a love of literature as he sang to me, read to me or told me about his experiences. I work as a professor at the Santa María University, which is also the place where I studied. I am the heterodox mom of humans and furry pets and I am becoming increasingly passionate about storytelling.

2 Comentario sobre “Fabiana Still Talks to Her”