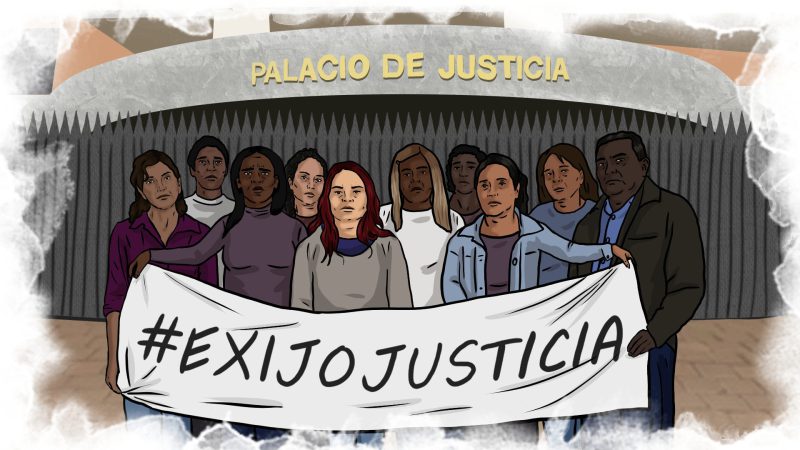

Between 2016 and 2024, almost 15,000 people have died in Venezuela at the hands of the security forces. Many of the victims were young black or brown people under the age of 30 who lived in the country’s slums. In 2019, some of their mothers banded together to share their grief and keep each other company while at the courts and prosecutors’ offices. The number of Madres Poderosas has just been growing ever since.

Between 2016 and 2024, almost 15,000 people have died in Venezuela at the hands of the security forces. Many of the victims were young black or brown people under the age of 30 who lived in the country’s slums. In 2019, some of their mothers banded together to share their grief and keep each other company while at the courts and prosecutors’ offices. The number of Madres Poderosas has just been growing ever since.

ILLUSTRATIONS: IVANNA BALZÁN

ILLUSTRATIONS: IVANNA BALZÁNCarmen followed the same routine she had stuck to every week for five years. She left her La Dolorita home at 7:00 a.m. and took a bus to Petare. There she got on another bus that took her to downtown Caracas. She walked for about 20 to 25 minutes to get to the courts. As usual. But things were different that day.

She would not press for progress in the case of Cristian Alfredo Charris Arroyo, her only son. She would not ask for the umpteenth time why the police officer who killed him was still free, wearing his police uniform and working. She would not photocopy the file with the details of the crime to find out if there was anything new.

Nothing of the sort.

On that 16th day of the month of January of 2024, the judge was scheduled to announce his decision in the case of Aljerdy Victorino Pacheco Rengifo, one of the policemen involved in Cristian’s murder.

Carmen didn’t know what to expect. She was a little scared. Already inside the courthouse, she suddenly started to cry. “What if he is convicted to a too short prison sentence?” she wondered.

“F*ck, Carmen. You need to keep your sh*t together. They can’t see you like that.”

Ivonne Parra, co-founder of Madres Poderosas, an organization they both created to bring together the relatives of victims of extrajudicial killings and demand justice, was by her side. Her words were like a lifeline in that whirlwind of emotions.

And then they heard the judge’s ruling.

“He has been sentenced to 23 years and 15 days imprisonment.”.

Carmen found out that his son had been killed on his way home from his 26th birthday celebration. Over the phone. The morning of Monday, September 23, 2018.

“They killed him! They killed him! And they took him to the El Llanito hospital!” she was told.

Carmen didn’t understand what was going on and rushed to the healthcare center. Upon arrival, she was instructed to go straight to the morgue. She was in shock. Her mind had gone blank. It felt as if she was lost in an unknown world. As if time had stopped. At that point, from a distance, through that thick fog, she heard her niece say that the police report read that Cristian was a criminal who had been involved in cases of extortion, drug trafficking, robbery, and homicide. Carmen filled with anger. She was irate. Cristian was a barber and practiced sports. Why on earth they were claiming he was a criminal?

Right there and then, she made a promise to herself: “I will clear my son’s name.”

That’s exactly what she was doing, trying to figure out how to clear her son’s name, when she ran into Ivonne Parra and told her her story. They were both in Cofavic, a human rights organization that Carmen had been told could help her by a couple of nuns from the Missionaries of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ order.

Ivonne, as she listened to what Carmen had lived through, felt for the first time that she was not alone. She carried the same pain: her son had been killed by police officers. His name was Guillermo José Rueda Parra.

“They did the same thing to him as they did to mine. He was 20 years old and a good boy.”

The conversation went on, while they cried tears of sadness and rage. They told each other their tragedies. They were surprised to learn that they were not the only ones: as they were told in Cofavic, the number of extrajudicial killings in Venezuela was sky high. From 2012 until the first quarter of 2017, Cofavic had recorded 6,385 alleged extrajudicial executions (a staggering figure that would only rise in the following years).

They attended human rights workshops organized by Cofavic and learned that those deaths fell into a pattern: the victims shared a similar profile. They were black or brown, under the age of 30, and lived in vulnerable communities. The police would kill them and then stage a violent confrontation. Each case reported by the Special Actions Force unit (FAES), a special branch of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB), was included in a list that sometimes made it to the country’s official crime reduction statistics.

As they gradually got to know other mothers who had had the same experience, they came to the realization that they needed support to seek justice, because they knew it was not going to be easy. They had to face delays in judicial proceedings. They had to deal with the various forms of impunity. Carmen and Ivonne were just the living proof. They filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office as soon as their children got killed. They had been talking to the prosecutors for months. Yet, the investigation had not even reached the courts. They were exhausted because, in addition to the foregoing, things were complicated at home and workwise, for they had no job and no money to pay the attorneys’ fees, and they had grandchildren under their care who needed to eat and go to school.

They might have lost heart from time to time, but that did not stop them from attending the meetings. During a workshop, a defender from the Venezuelan Education-Action Program (PROVEA) walked them through the laws and the legal terms they needed to know, and taught them how to prepare and file documentation with the prosecutor’s office, which was vital because even the smallest mistake would mean a waste of time and money.

In so doing, they learned how to approach prosecutors who seemed to be avoiding working on their children’s cases..

At the beginning of 2019, after listening to a professor talk about the importance of keeping the memory of their dead relatives alive, Carmen reflected on an idea she had had somewhere along the road to organize a foundation whose work will include raising awareness among the young people from La Dolorita so that they do not fall prey to the FAES.

A psychologist with whom she discussed the idea recommended her to include the other grieving mothers she knew. Carmen called Ivonne, who told her that she would love to work with her in the project. When it came to naming the foundation, they considered putting their children’s names together, but it just didn’t feel right. They kept going to the prosecutors’ offices while dreaming of an organization that would bring together those who, like them, wanted justice.

In June of 2019, Michelle Bachelet, who was the United Nations High Commissioner at the time, visited Venezuela and met with victims of human rights violations. Carmen and Ivonne were amongst her guests. They had the opportunity to tell Mrs. Bachelet that their children had been killed, and their accounts were part of the 558 cases in the report on human rights violations in Venezuela that was published a few months later, where the Government of Venezuelan was expressly urged to put an end to the FAES operations.

That experience brought them closer together.

It was in Cofavic that they met Keymer Ávila, a lawyer and researcher who ran the Monitor of the Use of Lethal Force in Venezuela. He documented accounts like theirs, and had advised them to present their cases. He explained them the legal documents they did not understand. He even helped them with the bus fare when they didn’t have money to get to the courts or to the prosecutor’s office. Carmen and Ivonne felt that Keymer’s interest and support were genuine.

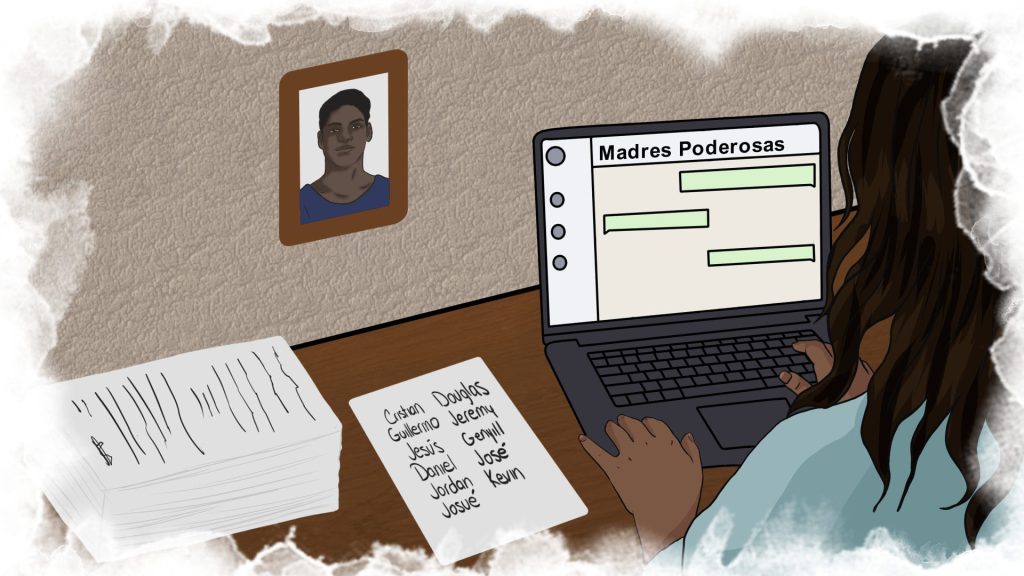

One day, while trying to agree on the place and time when they would meet to discuss their individual cases and discuss how to move forward with the idea of the organization, Keymer created a WhatsApp group and named it Madres Poderosas [Powerful Mothers].

Carmen and Ivonne looked at each other quizzically. The name seemed a bit childish to Ivonne, because it reminded her of an animated television series called the Powerpuff Girls, but he told them:

“You are powerful because of this fight you are leading.”

And that was their name. They would eventually identify with it.

Other powerful mothers joined the group.

First came Lina Rivera. She had a list of five family members who had been killed by the FAES: Jesús Rivera, her son; Daniel Rivera, her brother; Jordan and Josué, her nephews; and Kevin Figueroa, her son-in-law.

Then the relatives of other murdered young people joined in: Yexemary Medina, Douglas Escalante’s mom; Joselin Alcalá, Jeremy’s mom; Rosa Pérez, Genyill Chacón’s mom; and Samuel González, José Enrique González’s dad and the only male in the group. They were six now.

That was the fuel that kept them going in that pilgrimage in search of justice.

In 2021, having overcome a number of red tape hurdles, they succeeded in registering the Madres Poderosas foundation as a place where the relatives of victims of extrajudicial killings could come together and demand justice and keep company to each other.

They knew that together they were stronger.

They organized better. They used the WhatsApp group to plan their visits to the courts and the prosecutors’ offices to follow up on their cases. They had to go personally to inquire on the progress of their stuff, as none of the officials was going to inform them whether an arrest warrant had been issued for one of the people involved or of an upcoming preliminary hearing. They vowed to go to the aforementioned institutions more than three times a week. If one of them didn’t have an appointment, she or he would go with the others anyway.

The first few times they entered a courthouse as a group, many of the officials watched them and whispered. They knew them, but they still asked who they were.

“We are the mothers of victims of extrajudicial executions and we are here to demand justice.”

Things began to change. Some of the officials stopped talking down to them, and started to show more empathy and diligence. For example, they learned from some of the prosecutors that the reason why proceedings stalled was that they had no messenger to take summons and warrants from the prosecutor’s office to the courts, which meant that documents could be weeks in the backlog.

Some of the powerful mothers asked if there was something they could do, and they were told that they could ask for a “special mail” credential, which is an authority that made them sort of a request liaison between the two institutions.

It became part of their routine, and the others followed suit.

So, while some went to the courts with requests from the prosecutors, others photocopied documents that needed to be included in their files, or bought water or food for those who had not had breakfast.

Not only did they feel less alone, but the legal response flowed more effectively.

So much so, that Carmen finally succeeded in getting the first preliminary hearing on her case.

More have joined the pilgrimage: Urselis Valdéz, Omar Pérez’ mom; Millanyela Fernández, Richard Briceño’s mom; Martiza Molina, Billi Mascobeto Molina’s mom; Daisy Contreras, Andrés Osorio’s mom, and Odalis Machado, Carlos Galarraga’s mom.

Many more attend the quick legal counseling sessions given by volunteering lawyers such as Keymer, but as soon as they see that it is a delicate process, they opt out because they have more children and they fear that they too may get killed or threatened.

Some mothers have left the country because they feel more at peace far away than insisting on seeking justice.

When Ivonne heard the judge’s ruling that Tuesday, January 16, 2024, she cried tears of happiness for the first time in many years. “Yes, it can be done… Yes, it can be done. We must go on. We must go on.” And she celebrated the event as the feat it was.

According to PROVEA’s latest report on the status of human rights in Venezuela, the Attorney General’s Office had launched 50,855 investigations since 2018 for human rights violations, but only 1,842 people had been indicted by 2023. PROVEA estimates that 96.38 percent of the cases go unpunished. That happens in a country where, as per the Monitor of the Use of Lethal Force, 14,866 people have been killed between 2016 and 2024 at the hands of Government security forces.

The feat in question was followed by others.

Shortly thereafter, on April 30, a judge issued arrest warrants for three other officers who took part in the killing of Guillermo José, Ivonne’s son. Two of the offenders were transferred to the Rodeo III detention center, while one female officer was given house arrest because she was pregnant. Ivonne must demand justice for a while longer to get them all sentenced.

Several months have passed since Aljerdy Victorino Pacheco Rengifo, the policeman who killed Carmen’s son, was convicted. She has been told that he is being protected at the local detention center where he used to work. She hasn’t stopped going to court. In fact, she goes every week to demand that he be transferred to Yare III, the penitentiary he was originally assigned to.

“Our love for our children is greater than anything that could happen to us. Our goal is to have their names cleared and the murderers placed behind bars, because as long as they stay in prison, they are not going to kill anymore,” she says.

5731 readings