One day, in early 2018, Keyla, a 14-year-old pregnant girl, arrived at a hospital in Barcelona, in eastern Venezuela. She was all by herself, running a fever and leaking amniotic fluid. As soon as she was performed an ultrasound scan, the doctors knew that her baby had died. Dr. Nathali Arismendi, at the time an OB-GYN trainee, was amongst those who attended to her. Unknowingly, that young patient would teach her a lot.

First, she hid the fact that she had breast cancer. Then, when she could no longer keep it a secret, she refused to undergo chemotherapy treatment. The disease metastasized to other parts of her body. Milagros was confident that she would live to see the day when Kimberly, her only daughter, graduated as a medical doctor.

Nathali Arismendi was still a medical student when, during one of her first shifts, she pricked her finger while suturing a head wound on a homeless woman. Weeks after that work-related accident, she developed a fever and her lymph nodes got swollen. An HIV test came back positive, but she had no doubt in her mind that she had been misdiagnosed.

Martín is an 8-year-old Venezuelan boy. Like so many families, his decided to emigrate. In 2018, they settled in Mexico. Inés Araujo, Martín’s grandmother, who is a psychologist and an educator, joined them and stayed with them for a few months.

An occupational therapist, Erika Lezama left Venezuela for Perú with the expectation that she could continue to practice her profession. Having overcome more than a few bumps in her road, she finally landed what she thought would be the job of her dreams at a children’s therapy center located in the most exclusive area of Lima. The challenging experience made her realize the kind of professional she wanted to be.

Simple things such as receiving quality care, words of encouragement or a hug can mean the world to patients. That’s what Rubén Darío Carrero learned when he was just starting practicing as a physician. This is his account of the stressful and moving experience behind this reflection.

A medical doctor decides to donate a kidney to her sister to spare her from the grueling routine of dialysis treatment. This is the story of a transplant, an operation that many people in Venezuela can no longer opt for because on June 1, 2017 the Venezuelan Foundation for Organ, Tissue and Cell Donation and Transplantation (Fundavene), a body attached to the Ministry of Health, suspended the organ procurement and transplantation program.

Two Venezuelan medical doctors who graduated from the Universidad de Oriente reunite in Buenos Aires, Argentina. They start dating and eventually move in together. With the outbreak of the pandemic, they work grueling weeks and are exposed to high levels of stress.

In March of 2021, following a year of confinement due to the pandemic, dentist and university professor Francys Viaña traveled to Panama in the company of her teenage twins and her sister. Once there, she began to feel under the weather. She tested positive for COVID-19. From that moment on, what she had planned as a short vacation turned into a vertiginous and harrowing experience.

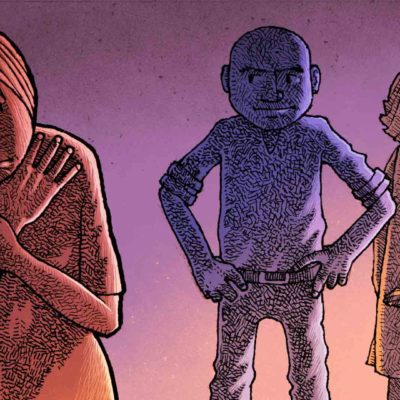

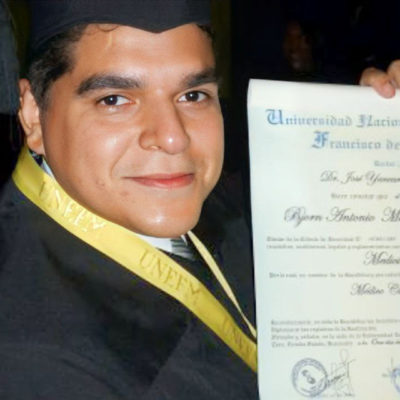

A kid who feels singled out because he is different. A kid who prefers to hang out with adults and who loves to read books and listen to the radio. A kid who is hypersensitive to many things around him. A kid who is labeled as a smarty-pants and whose behavior is considered as imprudent. Following a late diagnosis, surgeon Björn Martíinez delves into his memories to piece together the puzzle that is his own world.