That of July 28, 2024 was not just another election. Organized citizens, in defense of their votes, proved that Venezuela has a robust social fabric. This text weaves a thread into three testimonies of the gearwheel that was set in motion that and the following days by the citizens themselves to collect the tally sheets printed by the voting machines and make them available for the world to see. But there are more than three, for sure.

PHOTOS: IVÁN REYES // RODOLFO CHURIÓN // EFE

PHOTOS: IVÁN REYES // RODOLFO CHURIÓN // EFEElectoral witnesses stuffing tally sheets into tiny paperback copies of the Constitution or in their pants’ pockets, protecting them from harm or damage, for they are sacred.

One of those witnesses, from a slum in Caracas, commends herself to the Virgin Mary, summoning the divine company she feels she will need. She is on her way to the voting center where Chavismo has always won and where she has voted for them so many times herself.

People from the community bringing witnesses empanadas, coffee, a small container with rice and chicken…

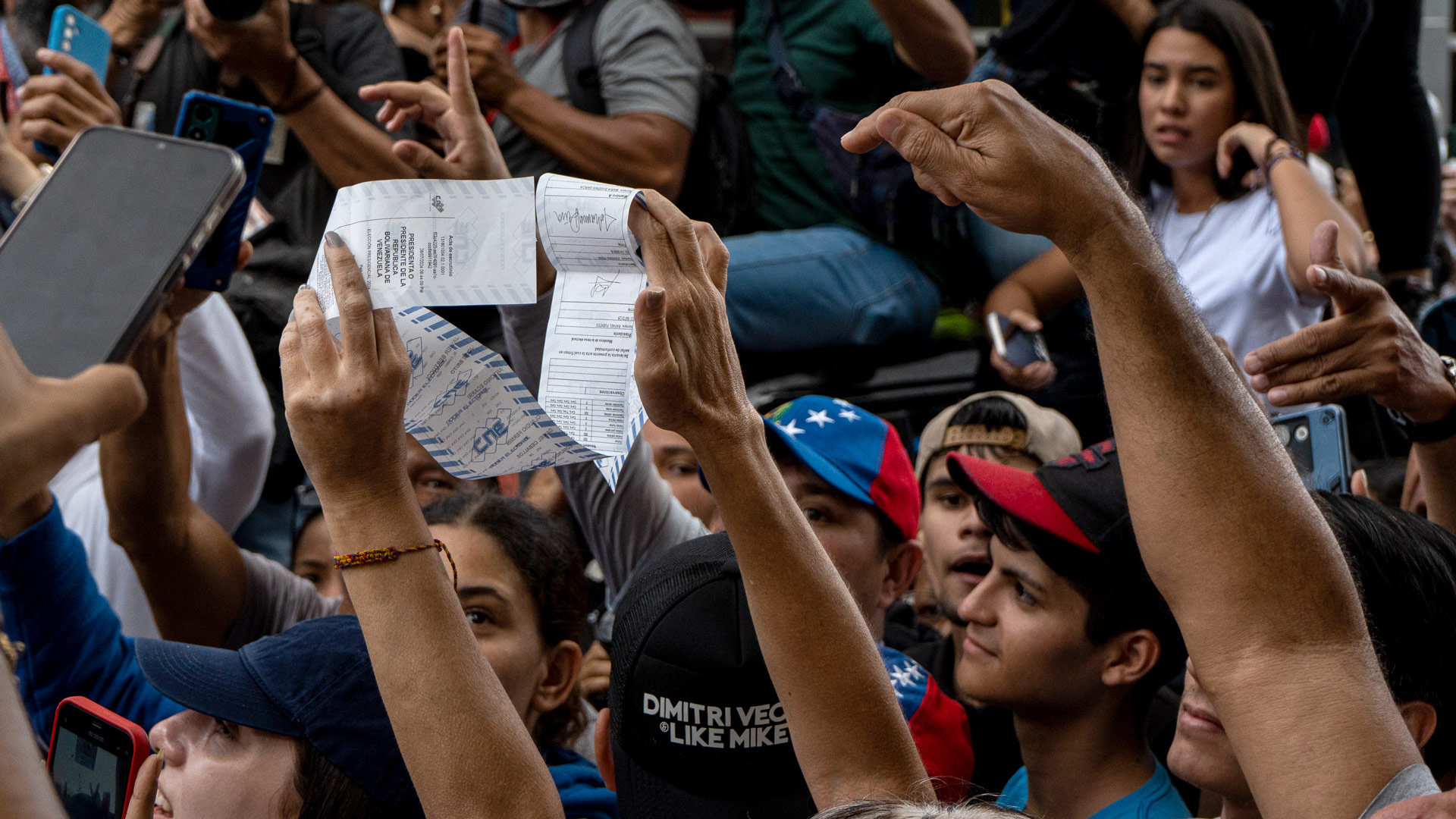

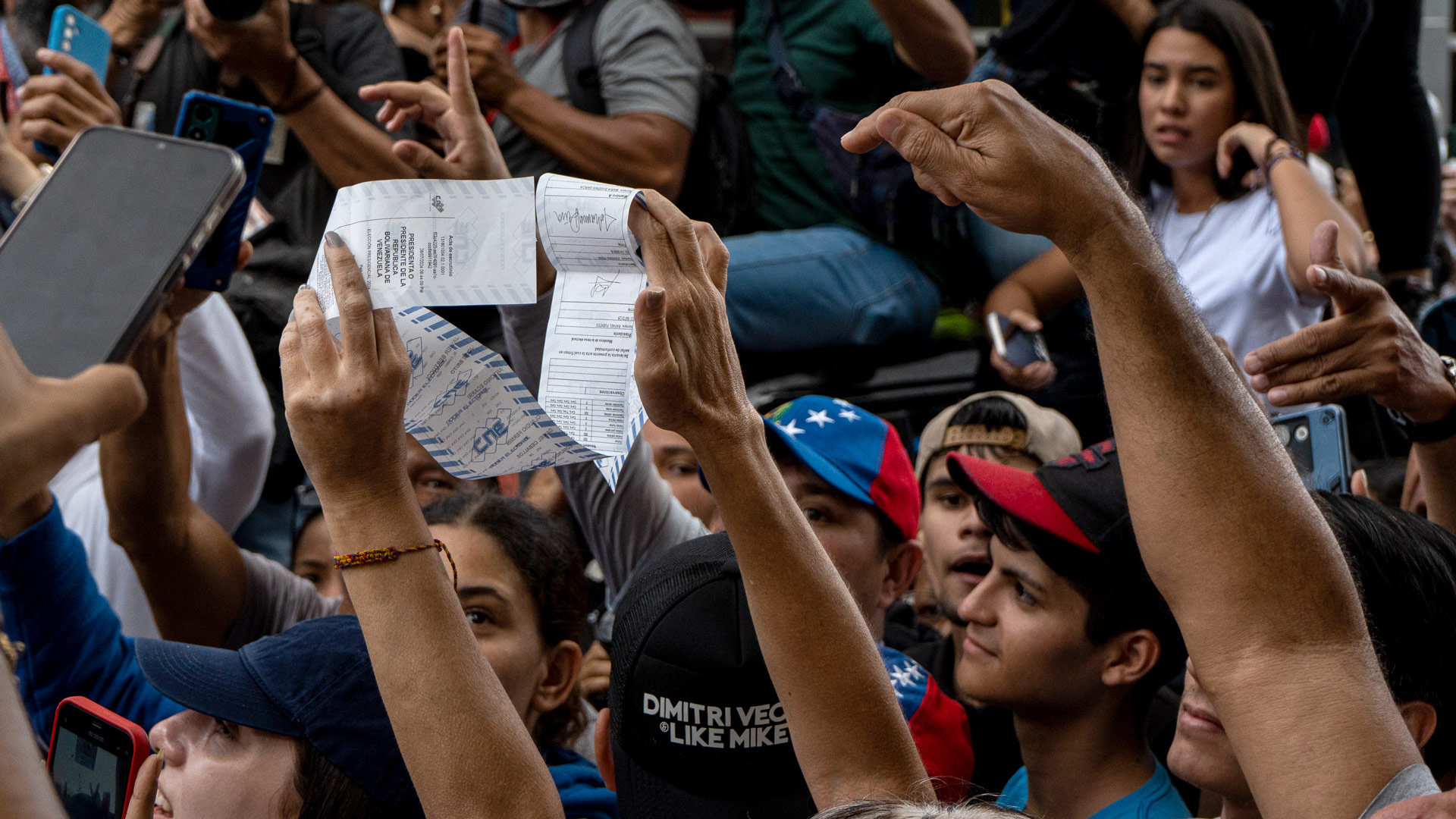

Voters, now outside their voting centers, demanding that witnesses be allowed to sign the tally sheets and inside the polling station during the vote count and tally transmission phase, and that they be handed the copy of the printout, as is their right under the law.

Voters, lifelong neighbors, escorting witnesses to safe places to keep them and the tally sheets out of harm’s way.

The tally sheets stealthily passing from one person to another until they arrived where they were meant to, some rushed on motorcycles at the risk of being blown away by the wind.

People shouting the results of their polling stations, clapping, crying tears of joy because opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia had just won. People flooding social media with the videos they had recorded on the spot in dim light.

People covering the mural on the Alfredo Sadel square, in Las Mercedes, Caracas, with large prints of the tally sheets at the top of which there were photos of the victims of repression, in a collective whisper of active peace as a form of protest.

And so on.

The American scholar Robert Putnam wondered why some democratic governments succeed while others fail. In his book Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (1994), he makes a comparative study of the quality of democracy in various regions in Italy, all under the same supra-institutionality; and one of his conclusions is that what defines the quality of a country’s democracy and economic prosperity is the democratic culture of her citizens.

Was not this, which can be given many names —civic humanism, virtuous citizenry, community spirit, networks of association, trust and cooperation, collective intelligence—, what was revealed in the presidential elections of July 28 in Venezuela? Does not the entire web that was woven for the defense of the vote fit that description? How about the political organization and leadership that managed to bring together the will of thousands of citizens?

There are numerous stories that show that this was not just another election; that it was a process that many citizens made their own, and one that speaks volumes of the strength of the country’s civic culture and social fabric —says Carmen Beatriz Fernández, a whip-smart expert in political communication.

There are so many stories.

These are just three.

The Story of Andrés

One week ahead of the elections, Andrés was contacted by people from Un Nuevo Tiempo (UNT), one of the two opposition political parties that managed to have their logo displayed on the ballot screen, asking him to design a program to totalize, project and analyze the voting results in Bolívar, a state south of Venezuela. Andrés, 54, lives in Puerto Ordaz, the capital city, and works as a business administrator with programming skills. As a volunteer, he had done as much in previous elections.

He was asked to coordinate a team. His liaison would be a mathematics professor, who today describes that Sunday’s experience as unforgettable, even though he got involved months prior. Even before the central campaign command of the opposition had defined its guidelines, they set out to consolidate an electoral roll with information from 98 percent of the 1,565 polling stations authorized in the state, which they did thanks to the in-tandem contribution of various political parties, civil associations, professional associations, volunteers, and the so-called comanditos [self-organized community-based voter groups].

That electoral roll would be the starting point for Andrés. On Friday 26, only two days before the election, he finally came up with the “how”: he would take an open source software that is generally used for corporate accounting and inventory, and would adapt it to organize the results of the voting centers as if they were products and cross-reference variables for multiple analysis.

He joined a team that included an information technology engineer, four college students, and two community leaders. As the idea was to project and analyze voter behavior, they picked the five largest voting centers in a number of parishes; in others, they selected centers with only one or two polling stations; and, more importantly, they chose some in traditionally Chavista centers where the opposition had never had representation. They would call all UNT witnesses in the 459 polling stations, who would report on voter participation at three different times on Election Day, and on the voting results; they would do so verbally first, and then by referencing the tally sheets printed by the voting machines. And Andrés and the team would enter all that information into the aforesaid software program.

This was part of an initiative that Andrés would call an “alternative” to the nation-wide logistics network.

Once processed, the tally sheets were sent to the collection center of the Comando Con Venezuela campaign command in Puerto Ordaz. The math teacher would pick them up and take them there. By 8:00 p.m., they had 40 tally sheets in their possession and could see the result: Edmundo González was winning “by a landslide” with 79 percent of the votes cast. They knew there could be some margin for error, but also that those numbers must have been very close to the actual ones because of the diversity of centers in the sample they had selected.

And around the same time, the witnesses started to complain to him:

“They do not want to give us the tally sheets.”

“They forced me out of the center.”

“I could not sign the tally sheet.”

Those witnesses had been accredited by the National Electoral Council (CNE). They had been part of nationwide intensive training workshop in mid-July and had a clear priority task: to demand the paper copy of the tally sheets, as established in the Electoral Processes Act, and secure them.

Fearing for their safety, the team decided to leave the premises where they were working and move to a private house. And at 10:00 p.m., seeing the program’s results so far and noticing the sheer anguish of the reporting witnesses, Andrés knew:

“They are going to steal the elections.”

He just knew. And the whole situation reminded him of the sense of purpose of what they were doing, which he summarizes in a cautionary banter he has shared countless times over the years to combat abstention among friends and family:

“If I am walking down the street and a thief wants to rob me, the only way I can file a complaint is if he does not steal my wallet.”

The tally sheets were the wallet.

They doubled-down on their efforts. They did not sleep a wink. The next day, the word was to go out there and get the tally sheets. They collected them, brought them in, scanned them, and processed them —in a loop that had sort of a spiritual connotation to it— and dropped them off at the collection center.

After two days, they were able to collect 300 tally sheets. And when the website that the Unitary Platform [Plataforma Unitaria] had designed to host them was made public, the team uploaded the rest of the information available for Bolívar. “We took ownership of those results,” says Andrés today. That is why he is sure as hell that, with the data he was able to upload until that Tuesday, August 6, Nicolás Maduro won in only 74 of the 1,129 polling stations in that southern state of Venezuela. “By the way, we are talking about very small polling stations that add up to no more than 11,000 votes for the government-backed candidate, against 8,000 for the opposition.”

The Story of Mauricio

It was a relay race, which in athletics involves the use of a baton, also called in Spanish testigo [witness] or testimonio [testimony]. It is a stick-like object made of metal or a similar material. In this case, the “testimony” was the tally sheet.

What the team coordinated by Andrés accomplished in Bolívar was replicated by many others in every state across the country, arriving in Caracas to find the next person to hand over the baton-testimony. Mauricio, a 34-year-old young man who works by day in commercial establishments in downtown Caracas, was one of those Venezuelan relay runners.

In the days following the election, he would not let go of his cell phone. Wherever he went, if he could get a good internet connection, he would scan and process tally sheets. He partnered with a friend because, in addition to supporting each other with their respective devices, they were not to work alone, for their own safety. He had seen a group of officers from the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) entering the building where he lived, looking for two young men who had been at the protests of Monday 29.

From the central campaign command, the parties were instructed to call for volunteers to scan the QR codes of the tally sheets. Mauricio got the call. He thought about his mom and about how worried she would be if he got involved, but he accepted anyway. On Thursday 30, he arrived at the Caracas headquarters in Quinta Bejucal. There were another 50 people about his age waiting in a room. The induction training session was only 10 minutes. He did not ask, but he knew that there were other groups in the adjoining rooms.

Before entering the room they had set up for the team he would be joining, he noticed some noise and activity: the various leaders of the opposition parties were entering the place, including a not so tall one who was peeking his head through the doorway, smiling discreetly. It was Edmundo González.

“How’s it going?” he asked them, as if he knew them from way back.

Mauricio recorded him with his phone: in the video, you can see when most of those present stood firm and greeted him with a “Mr. President”, brimming with optimism.

He went home and saw he had received at least 500 messages containing QR-code images sent via a WhatsApp group that had been specifically created for that purpose. He started scanning. He noticed that, in that flood of information, Maduro had gotten more votes than González in only 15 of the tally sheets.

Each voter comandito, an organizational structure created by the opposition for the elections, with more than 60,000 nationwide, was made up of around 10 people, including the captain or center coordinator, two “radars”, two coaches, and two witnesses per polling station. The radars’ task was to scan, on Election Day, the QR codes of the printed tally sheets by use of a dedicated app. Those of the many who were not able to do so, sent a photo of the code via WhatsApp to the command center, which was then forwarded to the scanning volunteers, day after day.

What mattered most is that each tally sheet had the elements required to verify its authenticity: the hash code (a unique identifier of each tally sheet in the CNE databases), and the code at the end, below the QR, which is obtained from the MAC address of the voting machine with a key that only the electoral body knows.

The tally sheets from hundreds of the 15,797 voting centers from all around the country could not be collected; nonetheless, in the first 24 hours following the election, the opposition had 73.2 percent of the tally sheets, with 6,274,182 votes for González and 2,759,256 votes for Maduro. Moreover, the gap between the two candidates widened with each incoming tally. A huge, unsurmountable gap.

It was the bees in that honeycomb who made it possible to collect such a large number of testimonies. Cases have been reported of military officials from Plan República, and even witnesses from the PSUV ruling party, defying “orders from above” not to hand over the tally sheets or remove opposition witnesses from the centers.

And then it was time for publication. Each scanned document was uploaded to the Resultados Presidenciales Venezuela website, which was designed by the same creators of the comanditos app. Although the site had been in the works for a while, it was not until Sunday that it was synchronized with the app. In the first 12 hours of operation, the website, though protected through offshore servers, had already been hit with 4-million software attacks. Also, 3,000,000 people had visited it.

The workload of the WhatsApp group created for the web protocol decreased as the days went by. There is a thumbs-up emoji on the image of each digitized tally sheet. Mauricio realizes that the second phase of this enterprise has been successfully completed. The tally sheets were everyone’s, and for all to see.

The Story of Daniel

Daniel’s tally sheets

Shortly after midnight on July 28, when the National Electoral Council issued the first report according to which Maduro had won with 51.2 percent of the votes cast, Daniel’s first feeling was that of disappointment, which then turned into resignation, for he had already considered the likely scenario that they would refuse to recognize the victory of the opposition.

But his mind —that of a 26-year-old young man who is about to graduate as an information technology specialist in Puerto Ordaz— reignited one hour later when he heard María Corina Machado say that Edmundo González had won with 70 percent of the votes and that they had more than 40 percent of the tally sheets in their possession, which they would make public on a website.

As he heard that, a series of things sprung to mind, including that it was imperative to keep the data heavily protected; that the tally sheets could be scrapped if they were made publicly accessible (i.e. fetched and its data extracted by use of software programs); that interactive charts and maps could be designed and shared; and that the data could be programmed for people to make queries by entering their ID number.

He could not stop thinking of possible solutions, particularly given the importance that such a collection of open data, which anyone can freely access and share, could possibly have. He knew it was all feasible, and even easily doable without the need for advanced technical knowledge.

It was a unique feeling. Imagine the huge impact that a simple website with photos and a button could have on an entire country. It could be a case study for other nations. It could be a great example for future IT specialists. Additionally, it would help change the minds of those who think that computer science is boring just because they picture computer scientists glued to their computers coming up with unintelligible codes.

Unable to sleep, when the link to the website was published late that night, Daniel set out to scrap it to create an “alternative” site. He feared the original site could be made to run slow, or that it could crash in no time due to traffic overload, which is exactly what happened. And he wanted to bring something to the Venezuelan table in such a historic moment.

All websites have a client (what the user sees) and a server (the data backup). People can crash or block a client, and fetch and extract the contents of a server, something that Daniel knew very well because he had done it before.

At 4:30 a.m., he tried to visit the website where the tally sheets had been uploaded: it was down; but he went to the server and it did return the data. He took the data and created another “client”. At 7:00 a.m. on July 30, it was ready to go; he shared the link with his closest ones and asked them to enter their ID number and see if it displayed the tally sheet of their polling station. And he proceeded as usual: he put his name and social media handles at the bottom of the page, and programmed analytics for user flow monitoring. Perhaps his aunt shared the link with her friends, and those with other friends, and fast and in real time, because Daniel would soon find out that there were 1,000 people connected. He got scared and deleted his user data.

In the space of five hours, the site had had 22,000 visits of people from all over the country. It was at around 4:00 p.m. when he decided to take it down. He had verified that the official website of Comando Con Venezuela was working properly and that his modest contribution of making data accessible when people needed it the most had served its purpose.

La historia de todos

The publication of the tally sheets, both in the original site and in several of the “alternative” websites, including the one designed by Daniel, made it possible for many of us to see what we saw on social media: a genuine citizen verification phenomenon. People sharing messages such as “The votes of Polling Station 6 have been verified and the tally sheets match” “Without a doubt, the photo I took of the tally sheet of my polling station (right) certainly matches the one published on the site (left). Nothing to add, Your Honor.”

There were people who started to do it spontaneously. And there were hundreds who responded to the invitation of a collaborative thread posted on X by Eugenio Martínez, a journalist specialized in elections, on July 30. Several hundred shared their photos of the tally sheet they had taken the night of the election, as well as videos of the vote count at their polling stations, contrasting that information with the published tallies. That is exactly what they did at Cazadores de Fake News, a Venezuelan organization that monitors disinformation on social media and instant messaging applications: they analyzed dozens of videos and photos and found exact matches with those published on the resultadosconvzla.com site.

Verification by Venezuelan citizens, and an actual global audit. That happened. The tally sheets were taken by scholars from prestigious universities from different countries, international media outlets such as The Washington Post and The New York Times, and the reputed Colombian Electoral Observation Mission (MOE), who made their own analysis and validated the internal data consistency, by doing so, validating the choice made by Venezuelans in the election.

It became a trending topic for technology and programming content creators, who shared their views on codes and torrents (file storing metadata). The voting results were displayed on a map of Venezuela for better visualization. The tally sheets were posted on Wikimedia Commons, which is the equivalent of Wikipedia for multimedia files.

The tally sheets of the Venezuelan election in every home and in the omnipresence of the infinite virtual world.

“When you release data, wonderful things happen… #OpenData,” wrote Carmen Beatriz Fernández in X, linking to a thread by Leonardo Maldonado, who took the data and analyzed the relationship between nighttime light luminosity (from satellite imagery) and the votes for Edmundo González at the parish level. The premise is that areas with higher nightlight luminosity are typically associated with higher levels of urbanization, greater economic activity, and higher population density.

It was the national and international communities who audited and backed up the tally sheets, in stark contrast with the actions by the National Electoral Council, which is yet to offer information supporting the official claim that Nicolás Maduro was reelected. The CNE has not published the results disaggregated by polling station and voting center, nor has it handed out to the different political stakeholders the database that feeds the bulletin with the voting totals. It has not carried out the three post-election audits provided for in the electoral calendar, nor has it reported on the status of the original voting material in Plan República’s custody.

There is a parallel story in this murky scenario: the phenomenon of the use of open data in the tallies collected by the opposition. According to a note from the Attorney General’s office, their publication is part of an ongoing criminal investigation in connection with the crimes of “usurpation of functions, forgery of public records, incitement to the disobedience of the law, computer crimes, and criminal association and conspiracy.”

And their publication would not have been possible had it not been for the bees in that honeycomb who protected the will of the people in an exercise of citizenry and democracy. “From the installation of the polling stations on Friday, July 26, it was a process that the people made their own, markedly democratic, and one that shows that this culture is in very good shape in Venezuela,” notes Carmen Beatriz Fernández.

As someone knowledgeable in electoral issues, she cannot get it off her mind these days.

“It is a theoretical debate that has been going on for years: there are those who say that democracy is strong and independent institutions; there are those who say that democracy is an ecosystem where freedom of participation, freedom of association, freedom of speech, economic freedoms, etc., converge. They are both right, but there are also those who claim that citizen culture is the most fundamental definition of democracy.”

That is why she feels that this election will set a precedent in the defense of the vote. And not only in Venezuela.

The identities of the protagonists of these stories have been protected for security reasons.

426 readings

Un Comentario sobre;