On January 20, 2018, a Taliban attack against the Intercontinental Hotel in Kabul was reported, one that killed 18 people, most of them foreigners. The news did not go unnoticed in Venezuela: among the victims were Pablo Chiossone and Adelsis Ramos, two Venezuelan pilots who worked for the Afghan airline Kam Air. The mother of the first, Yuyita de Chiossone, tells what happened that day.

Photographer: Alcides Gutiérrez and Misael Castro (Courtesy of La Prensa de Lara)

Photographer: Alcides Gutiérrez and Misael Castro (Courtesy of La Prensa de Lara)

On the night of January 20, I was watching TV when the news of the Taliban attack in which my son was murdered spread. On a Spanish channel I watched the news about an attack occurred in Afghanistan but I did not pay any attention to it. I thought it was one of those terrorist attacks that happen every 5 minutes, on every street, in every corner…

I never imagined that my son was there.

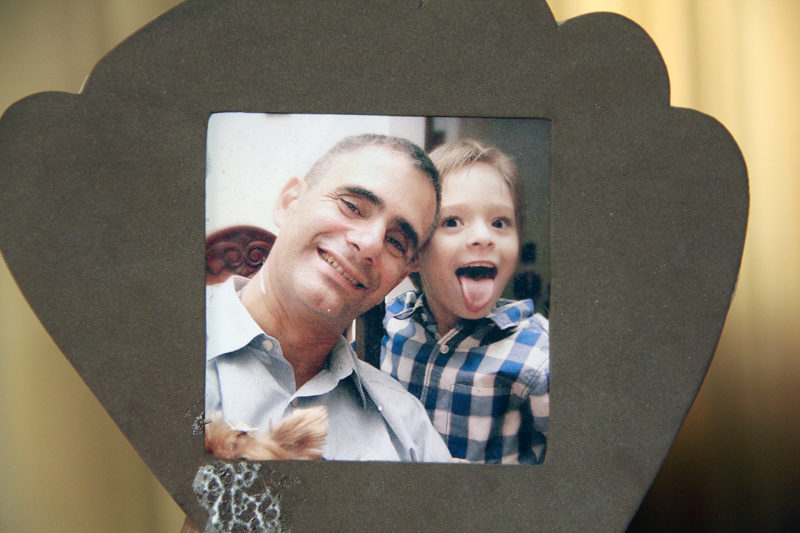

Pablo left Venezuela in May 2017. Before that date, he spent many days in front of the computer, looking for job opportunities for his career. He started flying planes at 17, when he was still underage. Flying was his passion.

Pablo’s story with airplanes is like a story of a dancer, whose body is ready for dance and only needs to learn the steps. His thing was the air, flying planes, and I knew that he would never have an accident in the sky. But I never imagined he would be a collateral victim of a war that was not his or his country’s war.

He was a civil and commercial pilot for Aeropostal, Avensa and Aserca, but some Venezuelan airlines have closed definitively and others have massively decreased the routes due to the lack of foreign currency and the shortage of aircrafts. My son, finally found a job in a job bank called Orion, which not only hires pilots but also seeks talent in different areas to place them in different jobs. And in May of 2017 he left for Johannesburg, South Africa. He was there for a while, flying for Orion, and they assigned him here and there.

We were in contact almost daily on the internet, and my husband, Pablo, also talked to him. I was his messenger because Pablo Sr. cannot speak out loud, as a result of a stroke he suffered.

In one of those many calls he told me he was going to fly to Pakistan. I felt very distressed, but I never learnt that he would go to Afghanistan or when he agreed to work there. If I had known that he would Afghanistan, I would have brought him back, at any cost, even if I had to drag him by the hair. I was terrified that he would go to the Far East (sic), and he would tell him when he was here: Not to the Far East! Because I know well how messy that area is. The terrorism. Everybody knows.

I begged him: “Do not go there.”

On Sunday, January 21, I got up and organized a luncheon at home because my 10-year-old grandson, Juan Pablo, who was leaving for Spain, was coming to say goodbye to us.

Then his mother called me:

—“Have you heard from Pablo Ernesto? I just read a story of a terrorist attack and his name is there.”

I grabbed the phone right away and called my cousins from El Impulso, the newspaper, and asked them, through their international press contacts, to find out as soon as possible what had happened.

At first I was in denial. I said: “No, he was not there. This has to be a mistake… It is.”

An hour went by.

My cousins did not call me, they came home.

When I saw them, I knew everything. But for a moment I thought: “What if he was alive?” But at the same time I was thinking: if he was recognized it is very difficult that there’s a mistake because he had a lock of white hair on the back of his head, which was his hallmark. After a few minutes, I lost hope.

I turned off the TV and put a game on the computer because I did not want my grandson to hear anything inappropriate. Then, his maternal aunt came to pick him up. After a while, I went with my daughter Juana Ines and my cousins to her maternal grandmother’s home, to tell my grandson what had happened.

His mother, his aunt, his maternal grandmother, Juana Inés and I were there. We had the hard task of telling him what had happened. And when Juan Pablo heard that his father had been murdered, he flatly refused to believe the news. He said that, no, that it was not him, that it could not be possible.

I remembered when my mother died, in 1956. I was a little older than him, I was 12 years old, and I spent a long time refusing to believe, in denial. I used to approach any lady I saw on the street. Anyone who looked like my mother, looked for similarities such as their height, hair color and texture … When I would see their faces, I would only find disappointment. At that time I used to say to myself: “She did not die, she got lost in El Ávila. She is not dead, she lost her memory.” Over time, I accepted that my mother had died in a plane crash in El Ávila.

But my grandson searched the internet and faced harsh reality soon.

He has assumed, as a child does and with all the harshness of the situation, what happened to his dad. I see in him the tools of this generation: information has great power. He seeks it himself and that has helped him to cope with it.

Alejandro Ollarves, the third Venezuelan pilot who worked for Kam Air, told me everything.

The siege lasted 17 hours. And Pablo probably died at 9:00 in the evening, in Kabul. The Taliban first launched a bomb, to blow up the guardhouse of the Intercontinental hotel, which is the Afghan state, and in which Pablo was staying.

They wanted to kill foreigners. Terrorists are not interested in murdering Afghan nationals or those in the Middle East, as foreigners draw more attention. My logic tells me that there was internal complicity because how would they knew who were in the rooms? They went floor by floor, and Pablo was one of the first to die because he was in the first rooms. Then they killed his partner, Adelsis Ramos, another Venezuelan pilot who was on the fifth floor.

That night a conference of the Afghan communications ministry was being held. A conference without security, Holy Christ! And the siege ended when the government killed the last Taliban.

It is all that I know. I will never know the exact circumstances in which my son died. I would like to know them, and that is what fills me with anguish, that’s like a dagger stabbing my heart. It kills me to think what Pablo Ernesto felt when he faced death, because he must have heard the explosions. I do not know if he took any precaution.

Would he feel fear? Could he face them? I do not know.

Did he think about his son? I’m sure he did.

Did he think about his sick dad? I’m sure he did.

He thought about issues to resolve, I’m sure.

I do not know if he was in agony after he was shot. If he felt pain… If he realized he was dying. I do not know… And that anguish buries the dagger stabbing my chest even deeper, and it will stay there until my final day.

Alejandro told me the story of a stewardess they murdered that day. That’s horrible! The girl locked herself on the balcony. She thought she was protected there, but she could not stand the cold of midwinter. When she went back in the room, they killed her. After that night, the company Kam Air planned to close operations because a big part of the staff was murdered.

On Monday 22, Juana Inés called the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which handled the case directly and made contacts with the closest diplomatic representation between Venezuela and Afghanistan, which is Iran. And I looked for support through the media and other institutions for the guardian angel of Pablo Ernesto, who is Alejandro. He was not at the hotel during the attack, but when he arrived he did not left my son alone for one second. He recognized his corpse, collected all his belongings and packed them.

He told me about the inhuman conditions in which Pablo Ernesto worked. It seems that Airline executives were very despotic with the staff. Of course, it is a different culture, different values. And for them, foreigners are undesirable, but they need them because their country is in chaos. That company would transfer money to Orion and they in turn paid my son.

He did not have life insurance, just medical insurance against accidents. My son accepted that salary – which was high and in dollars – as a kind of risk premium. Sometimes he had to fly at night with the lights off, because if the Taliban see a plane, they knock it down. He was besieged everywhere. His death was something that was going to happen anyway.

The Afghan government issued a statement lamenting the loss of “two very valuable pilots”, but that was the only thing he did, because the bodies were brought by the Venezuelan government, through a Turkish airline. Had it not been like that, my son would have been buried in a common grave and perhaps he would never have been found.

I know that for them my son is a collateral damage of his war. Just another number. But it is a collateral casualty of Afghanistan and also of Venezuela, because if he would not have left the country looking for a better life, he would be alive.

I have not said anything to my husband. He walks and talks with great difficulty, moves in a wheelchair and also has a permanent probe in the body. An impacting news can cause him another stroke. Although I know he knows it in the heart.

On Sunday the 21st, Pablo woke up at 6:00 in the morning with a concern, and said: “I need to get up”. Since he got sick, he left the bed late, but that day at dawn, he was restless. And while my little grandson was here having lunch, he only asked him about his dad. He said: “where is your dad? Have you talked to your dad?” He insisted, because my grandson and my son chatted a lot through their tablets.

Pablo thinks a lot about his son and asks with great difficulty: “what about those pending document from Pablo Ernesto?” I have not said anything, but in his soul, he feels that something is happening. Pablo Ernesto, being the younger of our two children, was very spoiled by his father. He had all the toys in the world, and I know that made him to leave the country: he wanted Juan Pablo to have good food and education, just like he did. That’s why he left home, to seek better living conditions for his son.

The death certificates that came from Afghanistan are generic, inadmissible anywhere in the world. My son’s says: “Pablo Ernesto Chiossone Ríos arrived at this coroner’s office. The undersigned, Mr. So and So, forensic doctor, certifies that he is dead.” That’s it. It does not say when he died, approximate time, and cause of death. The Venezuelan State filled out the form as it must be done for national and international standards.

We cannot understand that, but according to a failed state like Afghanistan, it was not possible to state that he died there, because Venezuela has no relations with that country, there is not even a consular office. Then it says “Lebanese Republic” and next to it was added “Islamic Republic of Afghanistan”.

After lengthy negotiations in Caracas, my daughter Juana Ines and I arrived in Barquisimeto at 6:03 in the afternoon and got off an army plane with my son’s body and belongings. On the runway of the Aero Club of Barquisimeto, which was Pablo’s house because it was founded by his grandfather, I held his portrait I my arms, the one that the staff of Aeropostal gave me. They framed it and surrounded it with white flowers. That night, I blessed my son, I said goodbye to him, and for the first time I saw his body and I cried.

On Thursday, February 8, at 5:30 p.m., I took the Piper Seneca captained by José Gregorio Ramírez. There I was with captains Alberto Urbano and Luis Bécquer Valero. We were flying with my son’s ashes. Our plane was escorted by others. We flew over the Jacinto Lara airport, then, flying in a low altitude, Captain Bécquer scattered the ashes.

I’m collected, because I vividly remember a teaching by my mother, who told me: “You rarely do what you want and what you like, but you always have to do what needs to be done.” And I keep that in mind. Therefore, every day I stand up, because I am responsible for what is happening.

I, Yuyita from Chiossone Ríos, am responsible for Juana Inés.

I am responsible for Pablo, my husband.

I am responsible for my grandchild.

And I have to go on.

I have to look for diapers, medicines, I have to buy food, stand in line to withdraw cash. All that I have to keep doing it. I cannot afford to give up.

But the dagger is there, stabbing my heart, and it will stay there.

Translation: Claudia Arteaga-Hung

2435 readings

I studied journalism at the Fermín Toro University in Barquisimeto, the city where I have always lived. Ever since I was a little girl, I have expressed myself through writing, and my love of literature is one of the few things that have remained unchanged in my life. I still aspire to become a writer and spend a lot of time in Paris.