One day, young Ana Rebeca Rivero started to feel that as if her legs had stop working. She thought it was the flu, but the incident would mark the moment when her memory began to fade. Although she recovered from that episode, it has happened again, and no explanation has been found so far as to what causes her condition.

“Mom! What are you doing here?”

Ana Rebeca Rivero could not believe her eyes: Esther, her mother, was there by her side, in Ibagué, the Colombian Andes town where she had been living for several months with her husband Joel.

“You’re back. You are OK now.”

Her mother’s answer puzzled her more, for she did not quite understand where she was supposed to be coming back from. She just said:

“Mom, you left your little house unattended.”

“Don’t worry, God is in charge,” Esther replied, relieved because her daughter was back from a two-week amnesia attack.

It was not the first time that Rebeca had lost her memory. It happened three years before when she still lived in Táchira and was starting college.

Three years… and she still does not know what is messing up with her life.

A quiet Rebeca, a Rebeca subordinated to what her body would instruct her to do… that was something hard for Esther to imagine. It was not like her child. Rebeca was a soccer and volleyball enthusiast. She was also a sharp chess player in the Colegio Don Simón Rodríguez in San Cristóbal, where she completed elementary school. She enjoyed herself and would not hurt a soul. And she was a good student. Like her two siblings, she excelled academically at the Simón Bolívar High School. The school was far from her house in Lomas Blancas and she had to take two buses to get there. Yet, nothing could knock her off the honor roll, for she earned all A’s and B’s.

Not even the alleged “flu”, with which it all began.

Urine appearance: clear; color: yellow; negative for ketone, and for bilirubin, and for nitrites, and for bile pigments. It looked like a very nasty flu, of the kind that makes your joints hurt. Esther had taken her daughter to the doctor, and the urinalysis results matched those of a typical healthy 18-year-old young woman like Rebeca.

However, the symptoms would not subside. On Thursday, it was her joints that ached; come the weekend, she could not walk.

Rebeca and Esther thought that it might be asthma rather than the flu. So they went to the Tuberculosis Sanatorium, where a pulmonologist checked her and was surprised by what she found: the doctor’s report stated that Rebeca was suspicious for reactive arthritis, which meant that Rebeca might have an infection. That would explain the swelling of her joints. Immediately, Esther took her daughter to the San Cristóbal Clinical Center for an appointment. The next day, an infectious disease specialist received them at her office. She prescribed Rebeca betamethasone dipropionate, injectable, for the swelling; aceclofenac, for the arthritis; and diclofenac, every twelve hours for two weeks, for the pain.

Despite the opinion of both specialists, neither Rebeca nor her mother had been given a certain diagnosis. The reactive arthritis remained a suspicion. In a medical facility located in the town of Cordero, in Táchira’s Andrés Bello municipality, the girl was ordered to take a vitamin B12 cocktail, which is prescribed for dengue fever; nevertheless, in the Military Hospital —where they also went when they saw no improvement— she was ordered to suspend it. In the meantime, Esther found an orthopedic surgeon who helped Rebeca walk again, though not well enough that she could go back to school.

Since Rebeca had already missed her second term, Esther talked to the teachers, who agreed to conduct remote evaluations and to average her first and third terms so that she would not lose the school year, considering her impeccable academic record. Of course, some people suggested that Rebeca was overplaying it and that she was being given a privileged treatment.

In spite of it all, Rebeca was the best student in her class and was appointed to deliver the valedictory at the Class of 2015 graduation ceremony. She was able to walk there thanks to the therapies, the treatment, the acupuncture sessions, and the prayers.

But Rebecca’s many comings and goings to the different doctors had made her medical history somehow confusing, and there were months when her body would not help with the symptoms. Besides, both mother and daughter were already looking into reactive arthritis as the culprit, so things needed to change. Or so they thought.

Rebecca had decided to become a public accountant, just like her mother. She would study at the Universidad Católica del Táchira, where she was admitted in early 2016. Following a stumbling start due to a tendinitis that prevented her from attending classes, she reenrolled in September of the same year.

After a long day of paperwork to register, at about 6:00 pm, someone offered her a ride to the bus stop. She was with Joel, her boyfriend. They were sitting there, waiting for the bus to arrive. The moment Rebeca tried to get up, though, her legs were like dead, and she began to convulse. Joel wouldn’t know what was wrong with her, since it was the first time something like this happened to Rebeca. He asked for help and managed to take her to the nearest Integral Diagnostic Center.

Joel’s father warned Esther, but she could not move from where she was because the buses that could drive her to the site were no longer operating at that time of the day. And Rebeca’s father worked in Casigua, in Zulia. Fortunately, Daniel and Ruth, their other two children, were close by and were able to see their younger sister; only that, for her, they were just two strangers.

Rebeca didn’t know who they were. She had lost her memory.

She was discharged from the Integral Diagnostic Center and recommended to see a specialist. It was just the beginning of a journey that would be reduced to visits to three neurologists, a neurosurgeon, a psychologist, and a psychiatrist, who added to her medical history. She would take carbamazepine, meloxicam for the headaches, and lots and lots of rosemary tea.

Still without a clear medical diagnosis, Rebeca, who had not regained her memory, was taken care of as if she was a child. They would take her out for walks and to church. She was getting used to her new and unique reality, very different from the active life she once loved to live. She needed to be in as calm an environment as possible because loud sounds made her faint and convulse.

Reality had also changed for her family. Esther stopped working full-time to be able to look after her daughter. Guillermo, Rebeca’s father, moved back from Casigua to help in whatever he could. Meanwhile, Ruth and Daniel continued studying, their minds split between school and what was happening at home.

That weekend, just two days after she had lost her memory, Rebeca began to convulse and her family hit rock bottom. They thought she was dying. They rushed her to the Social Security Hospital and from there to the Central Hospital. Before admitting her, she was ordered a CT scan, which they had to perform at the Policlínica Táchira medical center. And they somehow found the money to pay for it: God always provides, they thought.

Rebeca was admitted to the emergency area and was kept there for three days. At dawn on the third day, she convulsed again. Esther thought that her daughter was on the brink of death and, no matter how strong she was, she couldn’t help but to fall to pieces. Rebeca had been scheduled an MRI later that day. At the last minute, the neurologist at the hospital held off the procedure. His explanation baffled everyone.

“She is hiding something. Talk to her. Ask her. There is something that she is not telling you,” said the doctor of the Central Hospital, grudgingly, still unable to get it right.

Esther was shocked at the specialist’s response. It was out of place, no matter how confused one may be.

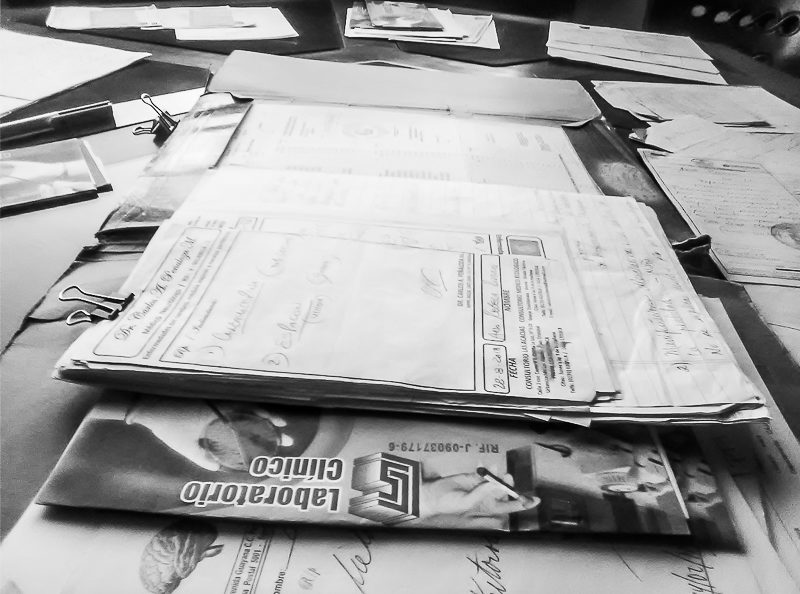

Regardless, Esther insisted on having her daughter seen because she needed someone to explain her what was happening with Rebeca. There were more CT scans, an electroencephalogram, and a series of laboratory tests. It all ended up filed in a 122-page binder with information on the medical consultations, the test results, the prescriptions, the invoices and bills, and the notes that Esther had been taking while researching the possible causes of her little princess’ condition.

That’s what they were: papers that said a lot but lead to nothing.

Rebeca had not been ordered to follow a special diet, so Esther would fix her regular meals of rice, salads, and pasta. She wanted to make sure that Rebeca felt as if she were at home in Lomas Blancas, for she had decided to stay from Mondays to Fridays at Ana’s, her mother, in Monterrey. It was close to the tuberculosis sanatorium, the Centro de Especialidades Médicas de Occidente medical center, the Clínica de Rehabilitación Médica Cho rehabilitation clinic, the Centro Clínico, and the El Samán medical and surgical center, which they both had to visit frequently.

Rebeca, who seemed to be resuming her life from square one, learned to play the electric guitar that her father bought her for her fifteenth birthday. And she never drift away from the Gethsemane Church. Her family has always been one of evangelical Christians, and they had to have faith, more than ever before, that Rebeca would be her former self again. God, they say, will pave the way for the doctors and the medicines to work their magic so that the ‘little one’ in the family gets back on her feet.

Six long months went by. Although nothing had changed beyond the walks that Rebeca would take with her friend Betsy, she was getting more and more at ease with her mother, now a virtual stranger to her. Rebeca was supposed to have had completed her first semester of accounting by then, but her family would not dwell on that.

One Sunday in March, as they were coming home back from church, Rebeca revealed that she had been recalling things for days, but that she had not said a word about it for fear of raising false hopes. Little by little, Rebeca remembered about her family. The youngest of the Rivero brothers was back.

They were overjoyed, but kept a close eye on her condition and took care of her as they had usually done. They kept going for walks with Rebeca, making sure that she was not exposed to loud noises that could upset her. But the seizures would not go away, like a reminder that there was still something unresolved knocking at their door.

Although Rebeca could not finish college, she was able to train as a chef. Much as she did when she was in high school, she excelled at the kitchen, despite the occasional seizures.

When she had almost finished her training as a chef, Rebeca decided to formalize her relationship with Joel and they moved to Colombia two years after that first memory loss episode. She was fully recovered. In March of 2019, they arrived in Ibagué. They were looking forward to welcoming Esther, who would travel there in December of that year.

When she had almost finished her training as a chef, Rebeca decided to formalize her relationship with Joel and they moved to Colombia two years after that first memory loss episode. She was fully recovered. In March of 2019, they arrived in Ibagué. They were looking forward to welcoming Esther, who would travel there in December of that year.

But in September she convulsed severely and lost her memory for two weeks. Esther moved her trip to an earlier date. The pineapple juice with ginger and cucumber, the meloxicam, and the rosemary tea were back on the scene.

And again, without a diagnosis, and not knowing for sure if the concoctions would work, Rebeca was able to come back from her trip into oblivion, and Esther —her eternal companion— and her husband were there by her side, reconstructing her memories as in the Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore movie.

Back in Casigua, Venezuela, Esther would not lose track of her daughter’s condition, nor her faith that Rebeca will recover for good. She will be there, even if she has to say hello to her daughter ‘for the first time’ more than once.

On February 27th of this year, Esther received a call from her son-in-law:

“How are you, Joel?”

“Rebeca convulsed and lost her memory again, Mrs. Esther.”

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

2151 readings

I am a journalism rookie with Zulian blood. I was born in San Cristóbal, but I am currently pursuing studies in communication and media at the University of the Andes. I am an amateur kneader. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

Un Comentario sobre;