In February of 2018, after hyperinflation drastically diluted his salary, José Alejandro Castro’s father migrated to Peru. The rest of the family would follow suit some time later. José Alejandro was the only one left in Ciudad Guayana, strongly determined to graduate as a bachelor of social communication from the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB) campus in Guayana.

In February of 2018, after hyperinflation drastically diluted his salary, José Alejandro Castro’s father migrated to Peru. The rest of the family would follow suit some time later. José Alejandro was the only one left in Ciudad Guayana, strongly determined to graduate as a bachelor of social communication from the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB) campus in Guayana.

In February of 2018, my old man emigrated from Ciudad Guayana to Peru. I accompanied him to the passenger terminal. I hugged him tight. I watched him drag his bags and climb up the bus’s steps; I waited for the unit to take off, leaving a trail of black smoke behind it. Before he said goodbye, with that calm and paused tone characteristic of the people from the Andes, he promised me that everything would be all right.

A few months later, in October of that same year, my mother, my sister, and my niece joined him. I stayed in Venezuela, all by myself, with the memory of my family departing.

Since November 2019, my dad has been working as a security guard in 12-hour shifts from Monday to Saturday. He clocks in at 7 a.m. and leaves at 7 p.m., or is it the other way around? Prior to that, he performed manual work for many companies, installing tiles, painting walls, welding doors, and making repairs. Later on, for a few months, he sold engineering equipment, called customers, and commercialized gear. He knows a lot about the business because, back in Venezuela, he worked for 27 years in a transnational corporation where he would go on to become a plant manager. He had graduated in 1989 as a mechanical engineer from the National Experimental University of Táchira (UNET) in San Cristóbal, where he was born.

I have been two years since I last saw him; now, when I look at him, it is through pixelated images during WhatsApp videocalls.

“Have you eaten anything, Son?”

“Yes, I have, Father…”

“How’s school?”

“OK, I guess… I’ve just submitted my final degree project, which is one of the requirements for graduation.”

“Good! Keep up the good work, Son; make the sacrifice worthwhile.”

It was in 2013 when he started contemplating leaving Venezuela. He didn’t like the direction the country was going. He was doing fine, though. He had been working for 22 years at Bombas Goulds de Venezuela, a subsidiary of ITT Gould Pumps; he was a plant manager and was charged with supervising the staff; his duties also included visiting stated-owned companies, where he would check the condition of the pumps, record the operating parameters thereof, and verify that measurements were within the appropriate ranges.

My old man used to wake us up every single day at 5:00 a.m. It took me a while to get up, just like my sister. I would toss and turn in bed and then I would pull off the sheets and grope about the floor, heading for the bathroom… and there he was, getting ready, shaving, putting on the polo shirt with the name of the company embroidered on one pocket. He would spend some time in that routine, until Mom reminded him what time it was and he hurried up.

“Move it; I don’t want to be late!” we could hear him yell from the kitchen as he got in the car.

He was never late.

He would drive my sister to her workplace and then me to the Antonio José de Sucre National Experimental Polytechnic University (UNEXPO). I was in my fifth semester of mechanical engineering, the same career as my old man. For some time, I had been considering dropping out because I didn’t like math. I would push tests, skip classes, and avoid bumping into professors, just to read novels, stories, and poems in the university’s hallways.

Dad took great interest in my studies, but he didn’t impose his will on me. He must have noticed my lack of interest because one afternoon, on our way home, he looked at me and said:

“Son, do you really like what you’re doing?”

hesitated. I dodged the question. I was faced with the same uncertainty as many Venezuelans in 2014. That was a year of protests all across the country. The young took to the streets; the universities’ classrooms were empty; classes had been suspended. The academic year had been virtually lost at the UNEXPO, and there was no transportation or cafeteria. Many students pulled out because of the situation, including me.

“Fair enough, but what are you going to do now?” he said when I informed him of my decision. What I did was supervise for six months a small auto gas shop that Dad owned. He put me in charge of receiving the cars, mostly from state-owned agencies, and overseeing the entire system installation process. Instead, I would spend my time reading. I would sneak into the office, where I always had a novel, a storybook, or an anthology, and I would kind of check from the window that the work was being done.

However, fewer and fewer cars were arriving at the shop and the business was going under. It wasn’t long before Dad closed down.

“Well, what are you going to do now?” the old man asked me again

So, I decided to study social communication because I wanted to learn how to write.

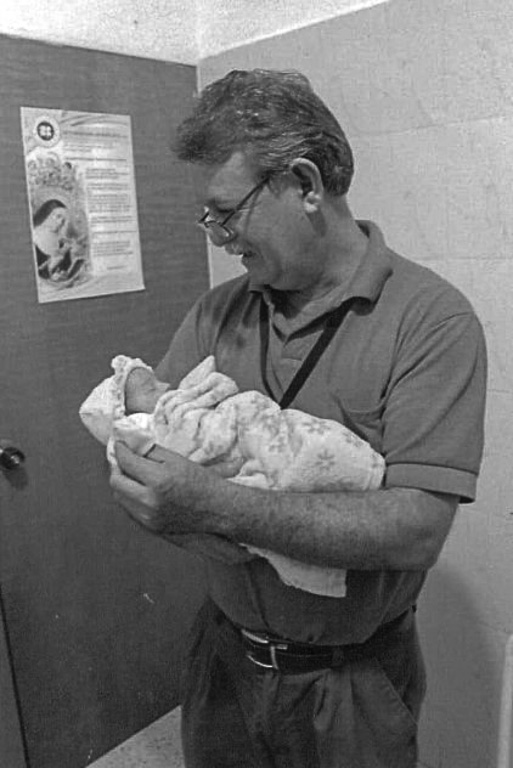

I started in 2015. At first, my dad was able to provide for my education. Despite inflation and shortages, Dad was still in a position to support a family of five: Mom, my sister, my niece (who had just been born), himself, and me.

That was until 2016, when hyperinflation hit the country. College tuitions increased, items in the basic basket of goods were nowhere to be found, and my old man’s salary, which in 2013 was USD 400.00, was now less than USD 100.00.

The old man was worried that his salary wouldn’t be enough to pay for my studies. At the same time, I was going through the scholarship application process at the UCAB. Anything that would keep me in. I filled out the application and provided information on my social and economic status, and a few months later I was approved the benefit.

I would see him in the morning: he was constantly checking his pockets (wallet, keys, whatever loose change he may have); he had grown a beard; his polo shirt was slightly wrinkled and the collar was halfway up; he was no longer in a hurry; he didn’t even honk the car’s horn anymore.

The only thing he asked, as we were driving to the university campus, was if I liked what I was studying. I would answer him enthusiastically that I did, that I now liked what I was doing, that this time I would graduate.

That’s when he took the decision to emigrate. His salary was only USD 67.00.

My old man’s plan was to save money and send me remittances from Lima. He was optimistic: he was convinced that his life would take a turn for the best there. But Lima was strange to him. It was the strangest city you’ll ever see, as Herman Melville would say.

“It’s like Caracas, but bigger,” he noted in one of our first WhatsApp conversations.

I knew the old man didn’t like Caracas. He is more into small towns. But there he was in another capital city; staying in a small room; sleeping on a mat, on nights that must have seemed endless to him; feeling the floor beneath his body, without a good blanket to fight the cold; bending his arms and curling up; looking for warmth where there was none.

It was difficult for me too.

I couldn’t sleep, and the news from Lima were not at all encouraging. Dad had to apply for the Temporary Resident Permit for Venezuelans, and the lines of people hoping to get it were very long. Some 600,000 Venezuelans entered Peru in 2018, but only 140,000 managed to obtain the TRP.

Back then, I would only talk to my mother, not to the old man. I made it a habit to call her very early in the morning. She told me that he was getting up early those months, that by 5:00 a.m. he was getting ready and that she would iron the clothes he will wear to go out and look for a job.

At 57, my iron-willed dad found a job doing manual work for a wage with 27-year-old boys in a company that hired Venezuelans, with no insurance or severance plans. My mother said that job offers for older people were informal in Peru and that my father was having a hard time finding something on his field.

I knew my mother didn’t want me to worry. She would tell me that everything was fine, that I should just focus on finishing my studies. Dad wasn’t around when we talked. He would often leave me a message, though, as if reminding me of his presence: “Your daddy sends his blessing and wants you to know that you are always on his mind.”

I remembered him and thought about him too. I remembered what he had told me about my career. I remembered that, in part, he was in Lima because he wanted me to graduate, and that, even though he was barely able to make ends meet and pay the rent and utilities with his salary, he was still sending me money.

We talked not so long ago.

“Father, how are you?”

“I have just got out of work, Son. How about you? On your way home from school?”

“Yes, Father. I have good news for you: I am expected to complete my degree program in February of this year 2020.

“What a joy, Son! Congratulations!”

He sounded very happy that day. I could hear him laugh with excitement.

“See? The sacrifice was worth the while. I told you everything would be all right!” he added.

And the news seemed to give meaning, if only for a moment, to all the hard work; to the city that he doesn’t like; to the distance.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program,  which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from 16 Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.

2405 readings

I am 28 and I have just graduated from the Andrés Bello Catholic University, Guayana Campus. I love a good story and how to tell it. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

2 Comentario sobre “He Told Me Everything Would Be All Right”