On Monday, February 18, 2019, three weeks before March 7, when a power cut left the entire country in the dark, Caimancito, a village located in the northeast of the state of Sucre, had already been experiencing an extended blackout that had only been interrupted by a few and occasional periods of electricity supply. That is where Mérida, aged 50, lives, and this is her story about how she has managed to survive for so long without light or power.

Photos: Ariana Ágreda

Photos: Ariana Ágreda

All of a sudden, something changed. It was as if the whole world had fallen silent. And still, very still. It was the night of Monday, February 18, 2019, and Mérida Martínez was getting ready for a good night rest after a long day of housework and chores. She turned off the light in the living room and laid down next to Carlos, her husband. A few minutes later, when she was about to drift off to sleep, she realized that she had forgotten the glass of water that she usually has on hand in case she wakes up feeling thirsty in the middle of the night. She got up to get it, but she did not make it to the fridge. About halfway thereto, she felt as though she was getting dizzy. Just another of her many and frequent dizziness episodes, for she is hypertensive. Everything around her turned pitch black.

Soon she would come to understand that it was something else: everything was dark because the power had been cut.

As the fans stopped working, clouds of mosquitoes started to flutter at will. Mérida could not fall asleep. She spent the entire night trying to keep the mosquitos off the bodies of her grandchildren, who were sound asleep. She did not want anything to disturb them. She thought that the electric service would be restored in a matter of hours.

Caimancito is part of the Chacopata parish, a community in the Cruz Salmerón Acosta municipality, which is a peninsula located to the northwest of the state of Sucre. It is an arid area in the Caribbean coast, with lots of beaches and salt flats. In the past, thanks to the exuberant beauty of its landscapes, Caimancito was frequently visited by tourists. Mérida lives there with her husband, two of her daughters and their partners and children.

The sun had risen on February 19 but the power had not been restored. Everybody went outside and heard the spreading news: The blackout had been caused by the explosion of some transformers in the Chacopata II substation, which supplied the area with energy.

“When is power returning,” asked Mérida, very much about to surrender to angst. Uncertainty was eating her up. The hours passed very slowly. In the fridge of the house she had fish, a few vegetables and a couple more things. “The food is going to spoil,” she thought, not knowing what to do to prevent it.

It was night again and darkness was deep and grim. The same thick silence lingering on that stretch of land in front of the sea.

They had already been an entire day without power.

Just another day, from the many that were to come.

Five days later, the communities in the town who had been affected by the blackout organized and held a first meeting. The neighbors were expecting the mayor of the municipality to attend, but he never showed up. “This one is going to be long,” thought Mérida. And she was right.

When in the afternoon of March 7, 2019 the lights went out in almost all Venezuela, and the country was left with no means of communication and without water, the people in Caimancito would not know about it because they had been disconnected from the world for three weeks and three days. That side of the peninsula had turned into an island. Into a powered-down, dim island. Dark as a tunnel.

Streets in Caimancito are not paved and are still made of sand. Its almost 4,500 inhabitants live in houses that have been recently renovated under the Great Mission Housing program. They were painted purple, apple green or orange. But they are now damaged by salt from seawater. There are rusty refrigerators, worn-out furniture and corroded humid walls inside.

During those days with no light, Mérida, 50, began to make mechuzos —handmade lamps from glass containers with diesel oil and old cloth— to try to lit up their nights a little. The smoke from the flames caused everyone in the house to have difficulty breathing, and now the children have asthma, but they have not been treated in the village’s outpatient care centers because of the shortage of supplies; thus, they have been forced to improvise at home with homemade herbal and plant-based remedies.

The lack of power made Mérida’s days increasingly complicated because she had already been dealing with food shortages in Caimancito. Before the massive blackout, she had to figure out how to feed the eight people that live under her roof. The generous sea often provided them with fish to eat, but how could they refrigerate it without electricity? What could she do so that it would not spoil? she asked to herself time and again.

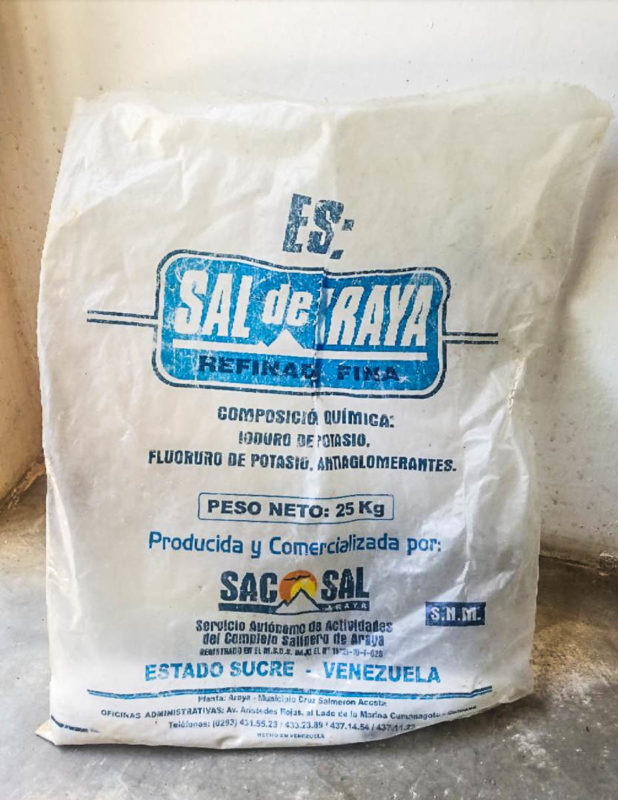

At some point, more tired than annoyed, she remembered that, back in the 1970s, her paternal grandparents resorted to a very particular formula to prevent unrefrigerated food from spoiling, even in temperatures exceeding 102 degrees Fahrenheit: they cured it with salt.

“That’s the solution,” Mérida said when the idea came back to her. Since she has high blood pressure, salt was off-limits for her. She could not ignore the doctor’s recommendations. She did not have money to buy her antihypertensive drugs and she had no choice but to keep her hypertension at bay by eating garlic cloves. Eating salt, she knew, would put her at risk. Regardless, and tormented with the idea that her sardines —the sole protein that she could afford— were going to rot, she decided to coat them with thick layers of salt. Nothing mattered anymore. She was not going to starve to death.

Since he began to implement the salt-curing technique, she has felt increasingly dizzy and her head hurts more.

In May, after almost three continuous months with no power, an electric plant arrived in Caimancito that, according to the mayor, would provide for a temporary solution. As soon as the plant was turned on, Mérida rushed to make fruit ice cream and prepare homemade sweets. It occurred to her that she could sell them to add to the household’s income. But just 24 hours later, the lights went out again: the power plant stopped working and stress and anxiety returned to the community.

Merida couldn’t hold back her tears this time around: she cried, she cried a lot. She felt aggrieved and feared that they would be left without the electricity for a long time again. The power was restored in Caimancito after three days, and with it a power rationing schedule that was not discussed with the neighbors. For five days the service was running only three times a week from 8:00 at night to 1:00 in the morning. Needless to say, Mérida had to wait for the night to arrive to do the laundry and the household chores. When they had power, they also had a little water.

There’s a lot of talk in town. They say that some thieves have taken advantage of the darkness to rob houses and strip them bare, carrying with items that are not in use because of the lack of electricity. As soon as Mérida heard about, she organized her family to take turns from late at night until sunrise to keep an eye on their belongings. They took down the lines from the light poles at the house’s entrance, removed visible and exposed water pipes and stored the light bulbs away; inside Mérida’s room there was even space for the fridge.

So, little by little, they themselves have been stripping their house bare. They stored everything that it doesn’t make sense to have at the moment. Because Mérida is firmly convinced that the light will not return. She says it assuredly. As one who has already become accustomed to that silence that spreads out through the house’s corridors and rooms.

“They have forgotten about us. It is not God who has forgotten; I am a believer. It is the people we voted for who have thrown us into oblivion.”

So many sleepless nights have made her a tired woman with a blurring smile.

Mérida does not know how to read or write and, for her, that is the reason why she has been doomed to stay in Caimancito. She is happy for the many people who have left the village —and the country—, because they are not living like her, plunged into that darkness. She thinks of her grandchildren and repeats to herself that she will never flee, that she will die on the peninsula where she grew up. In her village. In her streets.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

1424 readings

I am a journalist, an activist and a human rights defender. I insist on the need to document what’s happening in Venezuela. La Vida de Nos offers me a platform to show some of the vulnerability of my beloved state of Sucre.

Un Comentario sobre;