Upon returning from the United States, where he specialized in various scientific areas, Dr. Alberto Paniz Mondolfi founded the Zika Network in 2015. The idea was that the network would engage in the study of a virus that was then unknown in the continent, but it ended up becoming the Venezuelan Incubator of Science. They conduct research and train students of medicine, veterinary medicine and biology who, in turn, instruct neighbors on how to become citizen scientists.

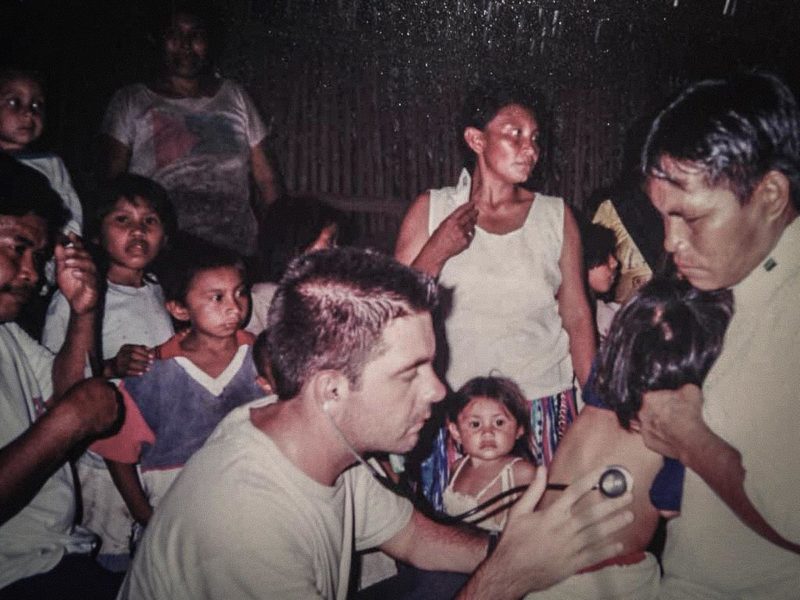

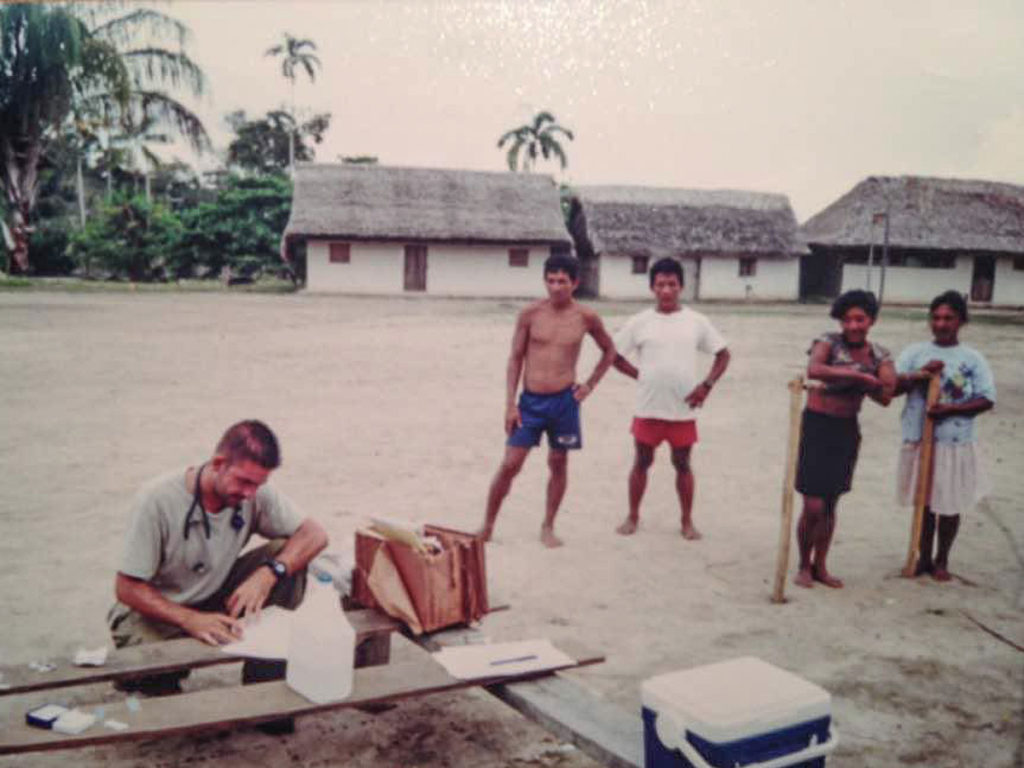

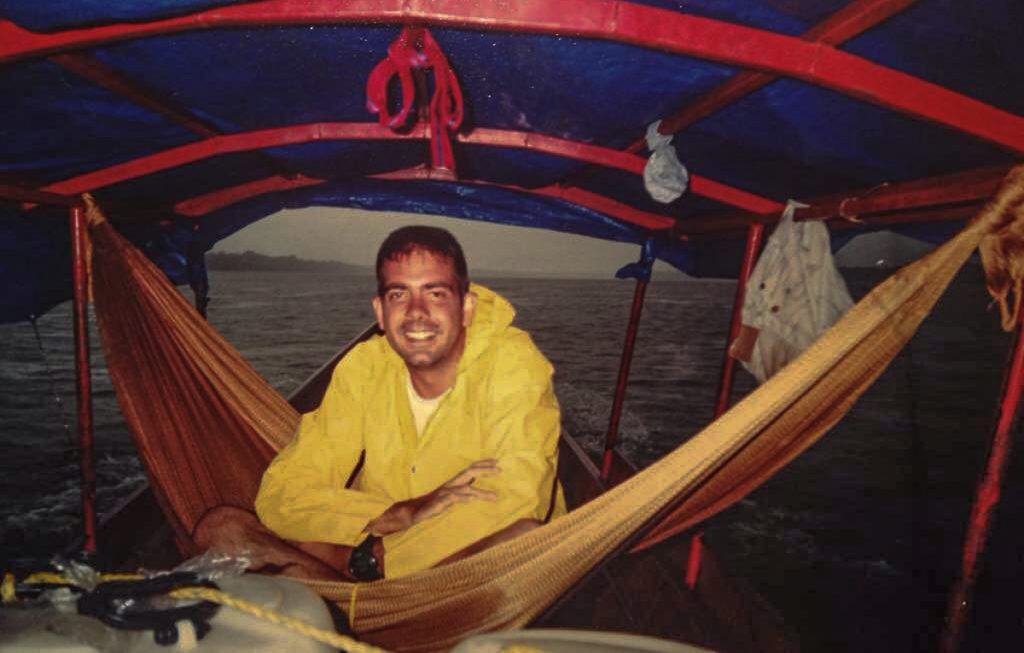

Photos: Family Album

Photos: Family Album

A fortunate and accidental discovery, but above all one that occurs when one is looking for something else. That is the meaning of serendipity, which is good to know because the protagonist of this story, in addition to being a scientist, experienced serendipity. That word resembles others such as chance and, why not, destiny, and Alberto Paniz Mondolfi’s life has had his share of them all.

Let’s start from the beginning.

Absentmindedly as always, Edgardo Mondolfi, Alberto’s grandfather, was looking for something inside his pockets. He was travelling in the United States with his wife, Ruth Gudat Gavens. It was her who was in charge of the finances and of driving the car; also, she knew him well. That is why, when she saw him digging into his pockets and trying to straighten out a crumpled dollar bill, she asked him:

“What do you need, Edgardo?”

“I am going to buy Alberto a book.”

Alberto Paniz Mondolfi was a medical student and a microbiology coach at the School of Medicine of the Central University of Venezuela, but viral infections were not his thing. In a book titled Cazadores de virus [Virus Hunters], his grandfather learned how Ebola developed in many of the places they had visited in Africa when he directed the Nairobi-based United Nations Environment Programme. Alberto was 5 years old. From then on and until his teenage years, he traveled extensively between Venezuela, the United States and Kenya.

Edgardo Mondolfi may not have been aware of it yet, but that day when he completed the three dollars that he needed and bought Cazadores de virus, something would change in his grandson’s life. Reading that book inoculated him with an interest in researching infectious diseases, not only in laboratories, but also in the countryside, which he got to know very well during his childhood years, full of adventures between expeditions to the states of Amazonas and Bolívar and in his city itself, Caracas. The city looked like a forest to him because he used to explore El Ávila mountain, which he viewed through the windows of the Liceo La Salle where he studied high school.

He also went on expeditions with his father, Nedo Paniz Nori, an architect, and when they returned home, they would project the slides of what they had seen.

“My father disassembled Jimmy Angel’s plane to repair it,” he thinks back. He was also one of the first to arrive at Lake Leopoldo, across the Cerro Autana, in the Venezuelan Amazon.

It never got boring. Just opening the fridge of his maternal grandparents’ house was like opening a spring of emotions: he could find a tiger head that would be dissected and studied by grandpa Edgardo, the renowned zoologist who described for the first time the cachicamo sabanero armadillo that Jacinto Convit would use in his research of the leprosy vaccine. In the kitchen of that same house, he would see animal bones being measured and dissected, or polyvinyl acetate being boiled in different colors which would be injected into arteries and veins. He remembers everything. Every expedition, every experiment, every scientific exercise.

And it would all make sense later.

During the seven years of his medicine studies, Alberto climbed EL Ávila almost daily. From over there, he could have a broad picture of the city where he was born, a chaotic landscape that combined the greenery of its mountains and the incandescent brick of Caracas’s neighborhoods. From over there, he would come to realize that, should a virus like those described in the book that his grandfather had given him spread, the tragedy would be of major proportions.

He completed his rural residency in Amazonas; before that, his interest in research made him become a member of the Biomedicine Institute while he was pursuing his undergraduate studies. For four years he went unnoticed by Jacinto Convit, the chief of chiefs there, until one day when the scientist, who had a reputation for being unsociable and grumpy, came across Alberto’s surnames while signing the payroll checks.

“And this Mondolfi, is he related to old Edgardo?” he asked his secretaries, who immediately summoned the young man to the office.

Convit —spearing with words but polite— received him and set the record straight about the stories that Alberto had heard about his personality. From that moment on, he became one of his mentors. It was Convit who advised him to pursue specialization studies abroad but to return to the country to put that knowledge into practice.

The United States was the destination he chose for his specializations in pathological anatomy, clinical anatomy, dermatology and microbiology. In the meantime, the great dilemma of whether or not to return to Venezuela was becoming an issue.

It could have been otherwise, because Gustavo Paniz, his brother, got arrested during an anti-government protest in 2014. The situation in Venezuela was not promising. He wanted to “rescue” his brother and take him to the United States. But, in the end, it was no more than a temporary period of anxiety. Like his grandmother Ruth, a 17-year-old photographer from Rochester, USA, Alberto did not want to stay in North America.

“The place is bursting with news. There is no time to get bored here,” said his grandmother in Spanish with a strong foreign accent, every time she sat down to “devour” the Venezuelan newspapers.

Not being able to say goodbye to her before she died, nor to her beloved Mondolfi uncles when they passed away, was another reason why he chose to return to Venezuela after finishing his studies. The visa system, which did not allow him to come and go as he wished, made him feel uncomfortable. He grew up as a free man somewhere between jungle and concrete, and he wanted to continue to be so.

He returned, not to Caracas, but to the state of Lara, where the true meaning of the word serendipity awaited him.

You’ll see why.

The states of Lara and Portuguesa are a gold mine for tropical disease research. It is a region where the major ones, namely leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, bilharzia and various systemic and cutaneous mycoses, overlap. Alberto Paniz Mondolfi had discussed it with Jacinto Convit: it they were to build a headquarters for the Biomedicine Institute outside Caracas, it had to be in Lara. A research center was built indeed in Sanare, one that is currently half abandoned.

Furthermore, his wife’s family lived in Barquisimeto.

“I think Convit was 20 years ahead: in the laboratory, he teamed me up with a very beautiful biologist, Alexandra Pérez, who grew up in Lara and is now my wife.”

There was nothing else to ponder. He would return from the United States and settle down to hunt for viruses in this western Venezuelan city.

That is how, in 2015, he created what would later become the Venezuelan Incubator of Science.

That year, the Zika virus disease, which, although foreign to the American continent, was a full-blown epidemic that claimed victims in several countries, including Venezuela. That made it all the more interesting from a scientific point of view. Alberto saw an opportunity there and, along with his friend Gabriela Blohm, a US-based medical doctor, and other doctors and professors from the Lisandro Alvarado Central Western University, he set up an action group for the clinical and epidemiological study of the viral infection.

They called it Red Zika [Zika Network]. Its primary goal was specifically to keep track of the virus and its consequences for health. They were able to do so with surplus funds donated by South African Juliet Pulliam from her laboratory’s research on Ebola. The Venezuelan team could then draw samples and run tests at the Emerging Pathogens Institute in the United States, in collaboration with John Glenn Morris, the director of the institute, which is attached to the University of Florida, and John Lednicky, one of the most important virologists in the United States.

The patients came to them —who met in the Antonio María Pineda Central University Hospital in Barquisimeto at the time— because they failed to get answers on what was really afflicting them. Doctors too began to see them as a chance to help shed light on this infection that puzzled the scientific and academic society alike. For the first time the virus was attacking not only Venezuela but the entire continent.

They began to travel through rural areas of the state that had been forgotten by science and detected endemics and epidemics by other neglected viruses.

That’s when serendipity came into play.

In science, as in life, there are fortuitous discoveries that determine the present and the future. Alberto intended to study tropical viruses in Lara, but he could not imagine that the Zika Network would expand into a large-scale research group, tasked with looking at all kinds of viral infections and their relationship with the environment and animals.

This is how the Zika Network became the Venezuelan Incubator of Science, which now operates in the Palavecino municipality of the state of Lara, there where a seedbed of students summoned by doctors derived into a set of networks, one for each disease.

Pediatrician Carlos Pacheco was the first to bring in one of his students; from then on, they would begin training young people, currently 20, with an interest for scientific research. At first, it was only medical students, but veterinary medicine and biology students would subsequently join in.

In addition to learning how to hunt for viruses, these young people also spread their knowledge to the communities —the same rural communities they met at the request of the first patients they evaluated in the early stages of the Zika Network— and form citizen scientists in the process. This is how they realized that when citizens are involved, research is strengthened because it is not limited to the recording of data.

Alberto Paniz Mondolfi and his team take science from the laboratories to the communities and, while doing so, they study, analyze and keep statistics of local and imported viruses. For instance, at a moment when the Regional Health Directorate of the state of Lara reported 10 cases of Zika, the network had accounted for 750 cases in that same period.

The results of their research have been published in prestigious scientific journals, including The Lancet Infectious Diseases and Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. And although they have failed to obtain local or national funding, the Incubator continues with projects such as the creation of Epiveritas, an epidemiology bulletin with which they intend to contribute to the study of the viruses that swarm in the region.

The next project that they have in mind is called “Deworming Venezuela”. It is based on scientific studies that show that deworming corrects the nutritional status and hemoglobin levels of individuals, increases school and labor integration, and boosts a region’s economic performance by 40 percent to 50 percent.

For Alberto, science is about doing something transcendental, lasting and replicable in time. And just as Grandma Ruth did not return to Rochester because she considered it a boring town, Alberto too, through serendipity, stayed in this Venezuela that moves at a thousand revolutions per minute, with the purpose of continuing the family adventure, hunting tropical viruses.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

2794 readings

I am one of the graduates of the First Class of Communication and Media of the Fermín Toro University. I switched from printed to digital media, where I am constantly learning to tell stories in varied and innovative ways.

Un Comentario sobre;