On a plot of land between the ‘José Antonio Anzoátegui’ International Airport, an important tourist complex and Jose’s cryogenic plant, there is a village called Las Bateas de Maurica, known to all as ‘La ciudad de los Mochos’ [TN]. Right there, in that postcard from failure, lives Germán with his wife and their 12 children in a house with no doors or windows. Photographer Samir Aponte has been visiting this place in eastern Venezuela for three years now with a view to putting their lives on record.

Photos: Samir Aponte

Photos: Samir Aponte

The bay of Barcelona is just a few miles from the capital of the state of Anzoátegui. It is the setting of spectacular sunsets crisscrossed by various species of birds, such as ibises and seagulls.

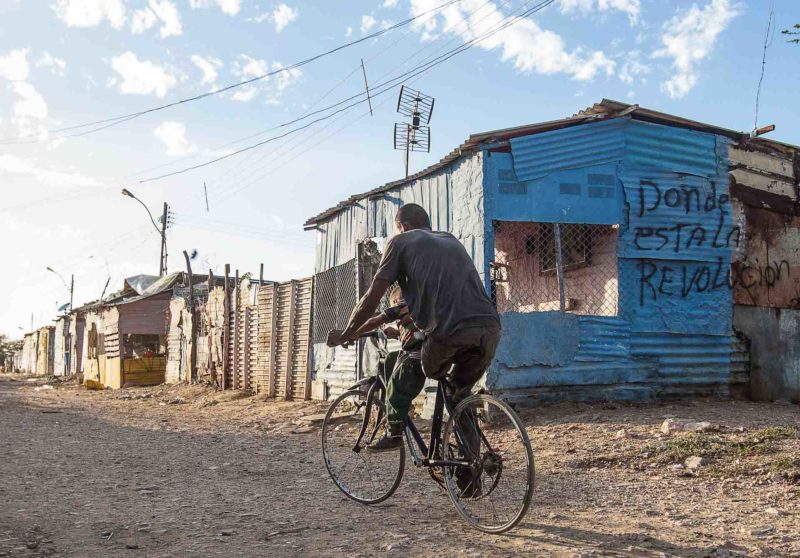

But a few meters from this peaceful landscape, bordering the ‘José Antonio Anzoátegui’ International Airport, the most important tourist complex in Barcelona, and with the cryogenic plant of Jose —one of the main refineries in the country— as a backdrop, there is a community of about 60 families and 100 children whose official name is Las Bateas de Maurica, but which is known to all as ‘La ciudad de los Mochos’.

Las Bateas de Maurica dates back 40 years, when a group of families invaded the land to build their makeshift homes there. It is a skyline devoid of any sense of well-being. It is a community that lives on the edge of life rather than on the edge of a highway. It is a world for all to see and on the margins of it all.

Passersby would rather not see this expanse of rubble and ruin. They say that you’d better not get in, that it is dangerous. But I did. Not once, but several times. As a matter of fact, I’ve been going there for the last 3 years now to take pictures of their daily life. Once inside, you will discover that it is less dangerous, but much more miserable than what you see from afar.

That is where I met Germán, a 42-year-old man who lives there with his wife and their 12 children and adolescents, and another baby is on the way.

Like all the houses in the area, Germán’s is in ruins. The cement-block walls and the zinc-sheet roof have been ravaged by humidity and corroded by saltwater, which eats it up inch by inch, day after day. His house has no doors or windows to protect the home’s privacy. “We don’t have any intimacy here. I sleep in a hammock in the living room and my wife in the room with the 12 kids.”

There are no public utilities in Las Bateas de Maurica. “The only thing we have is electricity and that’s because we connect our house to the highway posts. We don’t have drinking water. When we need to relieve ourselves, we walk to the huge surrounding terrain, and for a shower we go to the canal that irrigates into the beach,” says Germán.

That canal serves as an overflow area for the clean waters of the Neverí river, although sewage is also discharged on its course.

Germán has a physical disability. But in spite of that and of his socioeconomic and cultural condition, he goes out every day to figure out how to bring home the bacon and feed his children.

“Every day is a new struggle to survive. To wake up every morning in my hammock and hear the children cry because they are hungry is just agonizing,” he says. “That’s when my job of getting out there and venture into the concrete jungle begins. It is terrible to go out to see what can be done and walk through every space and place, trying to find something to take home. Going through the vegetable stands and grabbing the pieces that the vendors discard means to engage in a sort of give-and-take with people in the same situation. You need to be lucky when you rummage through the garbage of a butcher shop, because it is hard to find bones with some skin on them. I am fed up with this situation, but I have no choice.”

Germán says that when the evangelical Christian brothers visit the community, he asks them to look for him. “I want a change in my life. I would like to preach the word of God.”

However, it is not easy for him to follow the path of virtue. “When Hernancito was born, I did things to get him out of the healthcare center.” He had been admitted to the Dr. Luis Razetti hospital in Barcelona because he was born with a respiratory infection and he needed to take the last dose of an antibiotic so that he could be discharged and I could take him home. “I stole from a lady. I know that what I did was wrong, but I got the treatment for the baby.”

“I carry my life in one foot, with no direction, with no plans, aimlessly.”

[1] Translator’s Note: In “La ciudad de los mochos” (the city of mochos), the term mocho, as used in Venezuela, refers to people who have been born without or severed or amputated a limb or a part thereof.

Traslation: Yazmine Livinalli

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

2652 readings

I was born in Caracas but I am oriental at heart. I have an associate degree in graphic design and I am currently working as a graphic reporter for El Tiempo and as a visual designer for the Marinos de Anzoátegui organization.

2 Comentario sobre “I Carry It In One Foot”