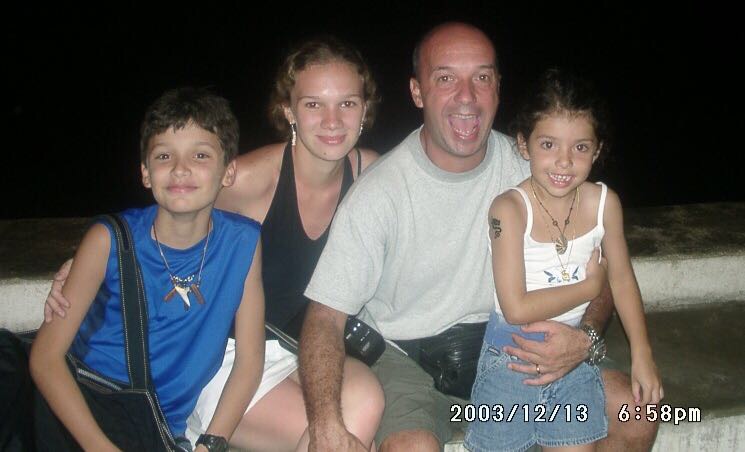

After 225 hearings, during which he walked 39,000 kilometers using handcuffs in his hands, Ivan Simonovis was never found guilty in the accusation of “complicity in aiding and abetting”, in the death of two people during the events of April 11, 2002. Despite this, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison. After 10 years in prison, he returned to a home he didn’t recognize, in which the children who grew up in his absence were no longer there.

Pictures: Family Photo Album

Pictures: Family Photo Album

Iván Simonovis asked to make a call. Using his memory, he recited a number and dialed. “I’m on my way home,” he told his 18-year-old daughter. On this occasion, the news was given by him because it was a good one. This time, he wanted to give her joy. Nine years and 229 days ago, when she was barely 8 years old, she received the worst news she had ever received: her father had been sentenced to 30 years in prison.

At 1:20 am on that Saturday, September 20, 2014, when the protests against Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela had left 43 dead, the same director of the Ramo Verde military prison went up to the 5th floor, entered the second cell to the left and told Hugo Chávez’s most emblematic prisoner:

“You’re going home.”

He didn’t believe him. He didn’t believe anyone in this government. A prosecutor of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and some representatives of the court who brought his case arrived. They had agreed to give him house arrest, but they warned him at dawn, when it is assumed that no decisions of this kind are made. He didn’t believe it until he got home, in Caracas. It was still early in the morning, in those hours when the darkness is thick.

He was wearing a sports suit and was allowed to change clothes. He put on a jean and a white t-shirt. This time they did not treat him violently; this time, the officials of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service were friendly. That dawn, they even asked him to take pictures with him.

Before that, Simonovis had been in El Helicoide, the headquarters of the political police of Venezuela, in Caracas. He was in a cell of four meters squared, in the basement, without ventilation or natural light. On weekends he could receive the visit of his wife and children in a common area where they almost did not fit.

Saturdays and Sundays, his wife Bony and his childrens Iván Andrés and Ivana, used to feel the sound of four large padlocks closing behind them, and they entered to a room where four very small tables were set up.

This place was attached to the bathroom, and it always smelled like dry urine; inside the jail there was one barrel with water to throw the pot, which was on the side where flies flit, because the trash pot also was there. In this place, every weekend for seven years was where the Simonovis family had to make a family reunion.

There were four chairs. Bony sat in one, in the other Ivana, and with his feet mounted on the chair, Ivan Andres, the primogenital couple’s son.

One of those days, like an allegory, Ivan Andres was reading Cien años de soledad [One Hundred Years of Solitude].

His dad entered the room. Ivana ran and threw herself at him. Bony kissed him. Ivan Andres remained seated, hugged him from the chair and he did not talk. He did not interact. His eyes were glued to the book.

When there was half an hour to complete the five days that the visit permitted, the eldest son got up, and sat down with his dad. Forcibly, since he was 12 years old, he had become the man of the house. That day, they talked like friends and the camaraderie was noticeable; they planned on the successive days in which they would not see each other, nor talk, even by phone.

In El Helicoide, Iván Simonovis had not allowed him to make a daily call, they did not let him go to the bathroom when he needed it, they did not let him eat hot food, or go out to sunbathe. He only had access to sunlight for two hours every two weekends. They never turned off the light of his cell and that is why, sometimes, he lost track of time and did not know if it was day or night. And it was that same light that made him lose his vision of the light.

The visit ended. When the family returned to the house and Simonovis to his cell, nobody said anything.

That Sunday afternoon, Ivan Andres snorted with pain: “How can I not to be furious?” He remembered the afternoon when he was on the court of his school playing soccer and a friend shouted at him on the court: “Simonovis, your dad was given 30 years in jail”. In retrospective, Iván Andrés used his memory to return until April 3, 2009, the day when the longest trial in Venezuela’s history happened.

It was four years of going to and coming to a court that was 100 kilometers from Caracas, where 225 audiences were questioned to 198 witnesses; 48 experts, 250 expertise were evaluated and analyzed, and 5,700 photographs and videos were seen. None of these pieces of evidence proved his guilt and in the Memorandum of Law, he has a register of all those days when he traveled to the hearings, traveling 39,000 kilometers using handcuffs in his hands.

Iván Simonovis, who was the former security chief of the Metropolitan City Hall of Caracas, was charged that day with the crime of “complicity in aiding and abetting”, without any proof of being the material perpetrator. He was accused of the death of 2 of the 19 people who died on April 11, 2002. As he said in an interview, this was like “a death penalty” for me. And 10 years later, Iván Simonovis was returned to his house the day he didn’t expect it.

The struggle of his wife Bony, to give him a house arrest had a burden of despair. She knew that he was in danger because one of his 19 pathologies are degenerative osteoporosis of the spine and neck, which weakened him, prevented him from lifting weight or even bending hard or fast.

This trip took forty-five minutes. From Los Teques, where Ramo Verde is, to Caracas, he toured a city that was foreign to him. The city was not the one he had known or guarded during the 23 years in which he worked as a researcher and expert in criminal matters. It was not even like that of April 11, 2002, that of the events for which he was detained. It was one that had proximity through the book Caracas muerde [Caracas bites] by Héctor Torres. A more hostile, perhaps, one in which even today has not been able to walk again.

That day, not only the city seemed foreign, but his house too. Because when someone is 10 years out of your space, or inside another one, those places in which the human being is not recognized, nothing resembles what it was, not even what was in the room of their children. He didn’t even recognize the furniture he had left in the room the last time he was there. He didn’t remember how they were. He had arrived at a new house.

In that space, everything has changed.

The first change: his children.

When he served five years in prison, his dream of freedom was to hug his family away from the walls of the prison. But that day he arrived home, and Ivan Andrés didn’t live there anymore. He was in Germany, 8,544 kilometers from Caracas.

—Daughter, I’m finally home— he said to Ivana.

There were no words. Only a hug.

That night, nobody slept in that house.

Every day, Simonovis gets up, has breakfast, does exercises, watches the news, plays with the two dogs in the house and spends hours immersed in a flight simulator. It would be the ideal state if it were not for the fact that five men armed with rifles guard it against the only entrance door. They are the same ones who take pictures three times a day and remind him that he has a provisional release and that there are other ways of being imprisoned. When the bell rings, it’s because El Sebin calls, as he did the morning of November 21, when, without an order of a court, he was taken to his headquarters in Plaza Venezuela, to question him about his health.

His two sons are now studying in Germany. Iván Andrés is a Social Communicator and is studying a master’s degree in Film, and Ivana is in her 2nd year of Social Work. Now the father is in the house and the children are out. One more time, fate is playing in reverse.

He loves rock. He likes to listen to U2, and plays Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and even El Canto del Loco at home, the Spanish musical group recommended by his son. He reads, and is currently writing his second book, after having done the first exercise with an autobiography entitled El prisionero rojo [The Red Prisoner].

In prison, he always tried to be with a smile and now in the house, his daughter has the perception that he is happier. After her father returned, Ivana spent a year with him, before going to school and during that time he took advantage to do what she wanted and couldn’t when she was a girl: washing the patio, fixing damaged things, cooking. Strengthening these moments together at home, as they said they would in each visit to the prison.

Despite being a sick man, in the last three years, he couldn’t be transferred to a hospital. A doctor visits him at home and to qualify his diagnosis they only say that he has compromised health. Bony knows that if he does not attend the cervical decalcification, with only a sneeze he could become paraplegic.

For the left-handed man who learned to shoot with the right, commanded rescue operations, and founded the first scientific police team in Venezuela, there’s little left. It’s not the same. Iván Andrés is perhaps right when he says: “The prison has never been closer and the freedom further away”.

Translation: Claudia Cavallin

This story was part of the work of Cigarrera Bigott’s “The Pulse and Soul of the Chronicle” XII Seminar of Narrative Journalism in 2018.

1937 readings

“To go with others in search of oneself.” These words by master Ginna Morelo define journalism. I have made them mine because I couldn’t be anything but a journalist.