The protagonist of this story lives in El Cedrito, a remote shantytown located in the vicinity of Mampote, in the state of Miranda. As a consequence of deficiencies in public transportation, this 8-year old boy has to ramble tortuously through many stops just to go to school. He is now on vacation, so he gets to spend his afternoons playing soccer. There are times when power goes out at home, but that is something that he has gotten used to.

Photographer: Régulo Gómez

Photographer: Régulo Gómez

Carlos’ sneakers are worn out. He doesn’t know how long he’s had them, but his guess is has been about two years. They now show the many layers of soil that has been gradually piling up from his playing soccer on a dirt field that is diagonal to his house, across a narrow asphalt street over El Cedrito, a small shantytown in the state of Miranda. The shoes, which used to be white, have turned brown, but they are still good for him to run until he gets tired.

These are the shoes that he wears now, while on vacation, to kick a borrowed ball in the soccer afternoons; but he puts on others to go to school: a pair of loafers that are as discolored and worn out as his sneakers, so much so that his big toe pokes out through a hole in his right shoe.

He has had to do a lot of walking in those loafers. A lot.

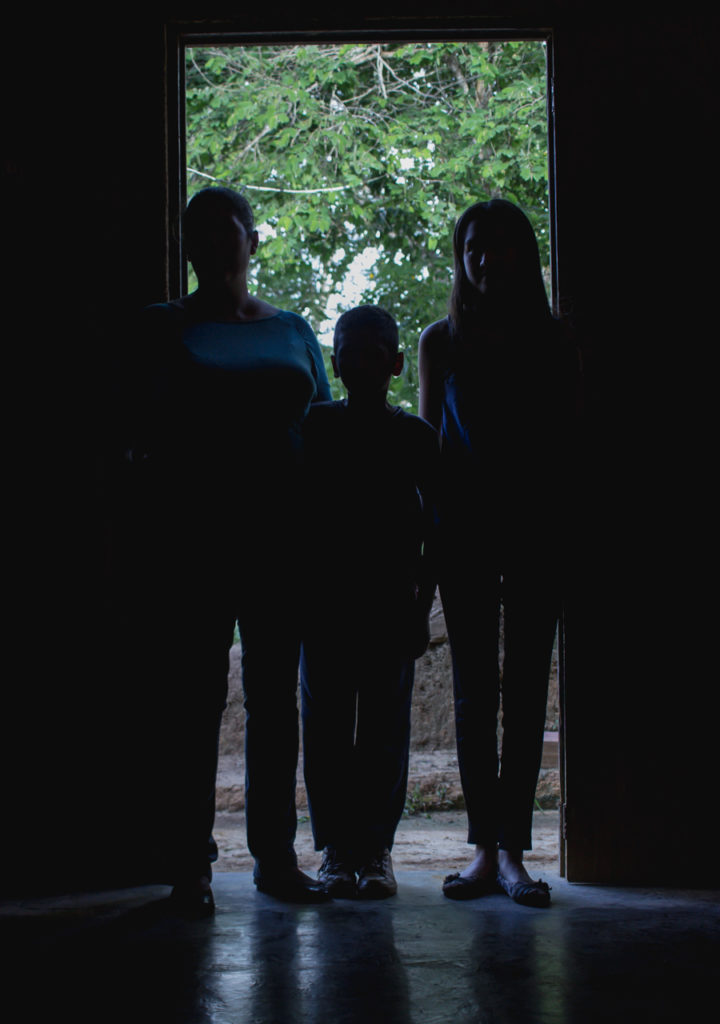

Arriving in the classroom means that Carlos, in the company of his sister Cristina, who is 13, has to go to great lengths. Cristina has already gotten used to it, but not him, who is younger and barely 8 years old. He gets exhausted: he has to walk long miles and wait long hours. It’s part of his routine.

—I wake up, have breakfast, brush my teeth, get dressed and go out to hitch a ride to Santiago.

Getting to school is a multi-stop journey.

El Cedrito and Santiago de León are about 2 miles apart. Or so read the improvised signs painted in black letters on a white wall, right across from a middle-class gated neighborhood. The bus stop is next to a post. Carlos, Cristina and their mother, who leave home at 5:30 in the morning, sit there.

Cars rarely pass by, so they have to walk down sloping curves to get to the bus stop in Santiago de León. They walk the distance lit by the rising sun. It takes them about 1 hour to get there, usually at around 6:40 am.

—If we don’t hitch a ride, we will have to go back— warns Carolina, their mom, as times go by and no bus passes by the stop or a private car whose owner would do them a favor and take them to the next stop across Club Mansión Mampote.

That stretch on foot is a 3-mile walk uphill, so they wait. Only if they finally get a ride will their mother give them her blessing and commend them to God so that they arrive safe and sound. Carlos and Cristina would jerk and lurch in the car along the roadside slopes and the craters that have been opening in the weed-invaded asphalt.

Once there, they have to wait for a small passenger van, which also takes a while to pass. That one will drive them 4 miles farther in a 20-minute trip along the old Petare-Guarenas road to the La Comunidad slum in the Plaza municipality of Guarenas, which is where the school is located. They get off in front of the ‘14 de Febrero’ high school, but they don’t get in.

That is not their school. They are still a long way to go.

—My school is three blocks away from there. There is a park. Next to the park you can see the Abel González Lima school. It has a zinc roof and its walls are blue and white—, Carlos says.

It is a race against time. They walk at a hasty pace because if they arrive late, past 8:00 am, they will have to go back home: the school board denies entry to tardy students. Some days they get in by a hair’s breadth, just as their classmates are singing the National Anthem in the schoolyard, before entering the classroom to discuss the day’s subject. But there are others when they are not as lucky and there is nothing they can do but to walk the 10.5 miles back to El Cedrito. So, if it is already 8:00 am and they’re still in Mampote, they don’t even bother.

Students are dismissed from class at 11:00 am. That is when they begin their trip back home, with its many stops: they will wait, they will walk, and they will ask people with cars to please drop them closer.

—One day Carlos waited almost five hours and couldn’t get a ride. He had to come home alone, all by himself, because that day I had decided to stay in. He arrived at about 5 pm, crying and really tired— recalls Cristina.

She says so in a low tone, imitating her mother’s earnest demeanor.

—Well yes; sometimes I get reaaaaaally tired— he adds, stretching his words.

And he smiles.

It wasn’t always like that. When Carlos was in the 1st grade, just a year ago, there was no public transportation crisis. Back then, Carolina could make sure that her kids got to the Abel Gonzalez Lima on time and that they didn’t have to go through such a tortuous ordeal.

Carlos and Cristina are on vacation, which means that they are taking a break from the long walks and the long waits. He spends many of his off days playing with his 10 plastic car toys, especially the yellow and black tractor that his godfather gave him when he turned 3 years old. It’s his favorite toy in the entire world.

He uses his right hand to drive the tractor past the legs of a hexagonal wooden table that embellishes the living room of the house that his parents built in just two months a decade ago.

A “vroooooom” runs from his mouth, his eyes fixed on the toy, which moves at a slow pace.

Carlos loves Mickey, The Avengers and Captain America, and superheroes. He used to watch movies with the family, but the DVD player broke months ago. It’s full of dust, lying next to a pile of quemaditos [burned DVDs] on the table with the flat screen TV. Carlos also spends time at his aunt’s nearby house, where he takes “reinforcement lessons” —as Caroline calls them—, thanks to which he has polished his handwriting and improved his addition, subtraction and multiplication skills and has learned to take dictation faster. He also enjoys playing rubber ball, kicking ball and soccer (his favorite sport) with the cousins his age who live in the adjoining house.

Those evenings are like this one of August 2018.

After a match, he runs back and arrives at his house’s backyard past 4 pm. He sweats profusely, his mouth gasping for air. He practices the sport because, when he grows up, he wants to be a soccer player like the Portuguese Cristiano Ronaldo, whom he admires. He hugs his mother, who is at the house’s entrance.

—Bless me, Mom.

—God bless you— replies Carolina. Then she kisses him on the head and gently combs his black straight hair, no matter how sweaty it is.

She grabs one of the sleeves of Carlos’ T-shirt and points to a yellowish blotch around the shoulder area. Carlos laughs quietly, as someone who knows that he has been mischievous.

—I ate a mango, Mom—, he says, still smiling.

His mother frowns because she is concerned about hygiene. She works cleaning at a nearby sector. It pays her only 5 bolivars a day, 5 bolivars from the new bolivars, the bolívares soberanos. She carries plastic bottles filled with water from work because they don’t have running water at home. And it has been raining lately, so they have various lidless large blue tanks filled with water. Carolina must work magic to make ends meet, and saving detergent, which is hard to find and expensive, is an example of how she does the trick. She can’t afford to buy more of it because she has just bought sanitary pads for Cristina, who has just hit puberty.

—Go take off your T-shirt so that I can wash it, and get a shower—, she asks him, with that gentle motherly tone.

Vacations and leisure days are quite different now from what they used to be when hyperinflation hadn’t wreaked havoc on the country’s economy. Carlos has those times engraved in his mind. He treasures the memories so much that he has several pictures from back then posted in the slits of his mirror’s wooden frame: pictures where he is happy in the circus, or happy in an amusement park, or happy at the movie theater, or happy with his sister, his cousins and Martín, his father.

Martín was his number one adventure companion. They played with the toy tractor. They made repairs to the house, like the time when they fixed the broken wooden door. Carlos would pass him the tools and Martín would do the hammering.

Things began to change at the beginning of 2018. No more outings to the cinema or to the amusement park. They were short of money and those were luxuries that they couldn’t afford. Unemployment forced Martin to move to a city near Bogotá, Colombia, where he now works in a farm tending to horses, a task for which he gets paid less than that country’s minimum wage.

Sometimes they talk on their aunt’s cell phone. Or they share voice notes over the smart phones of the volunteers who do social work in his community. They let each other know that they are loved and missed. But Carlos doesn’t say a word to Martín about his fruitless efforts at Santiago de León’s bus stop; much less about the tears that sometimes run down his cheeks when he has to wait for a ride or because he wants to see him again so badly.

—It is sad—, adds Carlos, matter-of-factly.

Ever since Martín emigrated, Carlos, his mother and his sister sleep together in his parents’ room.

—Mom, the box is here!!!

Carlos shouts from the backyard when he sees a local man approaching with a box on his back. The box has been stamped the letters “CLAP”, which is the acronym for Comité Local de Abastecimiento y Producción [local committee for supply and production].

—Mom, mom, the box!!!—, he repeats.

Carolina gets excited because she has been waiting for the combo of government subsidized food for a month and a half now. Just a few weeks ago they had finished all the products in their last box.

—For breakfast I eat arepa stuffed with egg, cheese… sardine… fried plantains!!! Yummy!!! And bologna, once in a while—, Carlos exclaims.

At dinner, though, his plate is not always filled with food choices. He has no idea of the math that Carolina has to do to make whatever bananas or the one kilo of rice they have left last. There are nights when they only get to eat one type of food and have to choose between banana and rice. But they always sit together and grateful at the pantry’s table, its red legs now scaling from the humidity, dressed up with a pink-and-yellow flower tablecloth. Carlos’ seat overlooks the house’s door; his father’s seat, to the left, is empty. Blackouts are a common occurrence; when they strike, they eat their meal in the dark.

—Lights go out here all the time. We will light candles, eat and go to bed—, he adds, without much excitement.

Carlos says he’s used to it, but Carolina is not yet. She unplugs her few appliances to prevent the voltage surges from subtracting from their useful life or burning them. She already has a computer, a TV set and a refrigerator that have been damaged because of fluctuations in electrical frequencies. Light bulbs have been burning out gradually; there are now only three left: one in the living room, one in the kitchen and one in the master bedroom, where the three of them sleep. She hasn’t been able to replace them.

But that is not on her list of priorities. What she would like the most is to buy her son new shoes for the upcoming 2018-2019 school year. She saw a pair of loafers in a shoe store for 50 million bolivars (500 bolívares soberanos). Even Carlos knows that they are impossibly expensive. So, she plans to repair the old ones with nylon thread. Carlos finds it’s funny that his right big toe peaks out through the shoe’s open upper. It even makes him laugh.

He wants to go back to school. If he doesn’t become a soccer player, he aspires to be a doctor.

—So, first I will go to a university to study and then I will cure people.

His mother and sister smile with him.

Translation: Yazmine Livinalli

The names of the children in this story were changed to protect their privacy.

This story is part of the “The Children of the Crisis” series, which was written in association with the Community Learning Centre (CECODAP, by its Spanish acronym)

2135 readings

I was born and raised in Caracas, Venezuela, my favorite classroom. As a journalist, I am constantly learning and tugging at people’s heartstrings with words. I currently cover politics for El Pitazo.