Judith Bront has lost count of funerals of children she has attended. Children treated at J.M. de los Ríos hospital, like her son Samuel, with whom she spent 12 years struggling for his defective kidneys to allow him to live a moderately normal life. That pediatric hospital in Caracas, the most important in Venezuela, was her home and it continues to be so. But now, her fight is a different one: to prevent the situation there to be buried in silence.

Photographer: Gabriela Carrera

Photographer: Gabriela Carrera

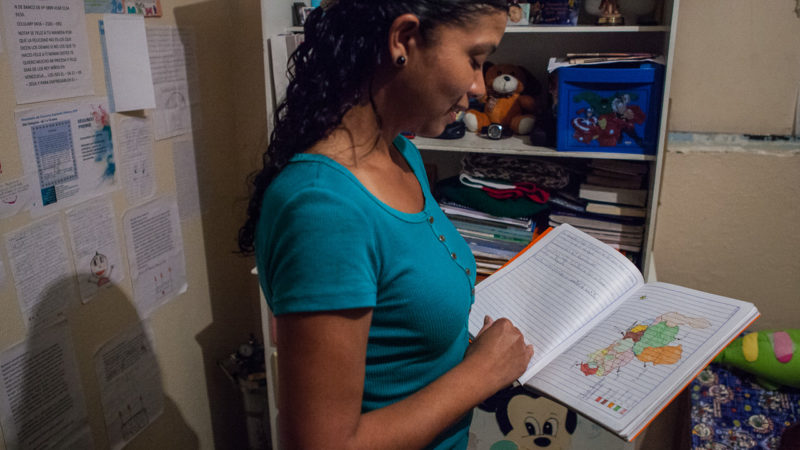

Her outfit is dramatic. Her eyelids made up in lilac -matching the sleeveless tank top- and her hair, very long, very smooth, almost liquid-looking. She is dressed in dark colors. Black pants, violet top and that hair, cascading from the top of her head like a mournful cloak.

In return, her body figure is compact and attractive. It would not be surprising if she had an athletic past. Her character is vivacious. She is eloquent and her detailed recount of the facts has no trace of resentment. On the contrary, she does not seem to harbor any feeling towards the world other than tenderness and curiosity. If you see her walking around a shopping mall, you would not think that she bears a great pain inside nor would you guess the immensely courageous feat that marked her past. But not everything in Judith Bront Rodriguez’s life is what it seems. For starters, her hair is not even straight. “Actually, it’s pretty wavy,” she confesses. “But I stretch it… my family is black. Now, since I have a lot of time to spare, I flat iron it.”

Her body figure and that Olympic flair are inexplicable. Judith has spent more time in seclusion than many prisoners. It’s as if walking from the bed to the table where the syringes were worked for her like a workout routine with a personal trainer. The truth is that Judith spent the last 12 years in the hallways of a hospital and in the waiting rooms of pediatricians’ offices. Maybe her muscles toned up while waiting for the dialysis services and fighting with the doctors who would so often herald the imminent death of her son.

Samuel Alejandro Becerra Bront was born on February 19, 2005 at Dr. José Ignacio Baldó General Hospital, also known as El Algodonal, in Caracas. He was the first son of Judith and her husband, Miguel Ángel Becerra, whom she met while studying Law at Santa María University. Judith is a lawyer. You would not guess that either. You would not determine why, but you would bet she is a professional in any other career. A psychologist! That could be. Or an intensive care nurse, walking with those soft steps, trained in a thousand sleepless nights. The thing is that she married Miguel Ángel in 2004 and they settled down at her mother’s house. But that is a different story.

Ascensión Emira Rodríguez was born in Yaguaraparo, Sucre state, located to the east of Venezuela, where you can barely find the traces of a thriving past of cocoa plantations. At 15 years old, she moved to Caracas and got a job as a factory worker. In one of those factories, she met Giselo Serafin Bront, who, like Ascención, was from Sucre, was eager to work and had a single surname. In his case, it came from Englishman who supposedly arrived in Irapa from the island of Trinidad.

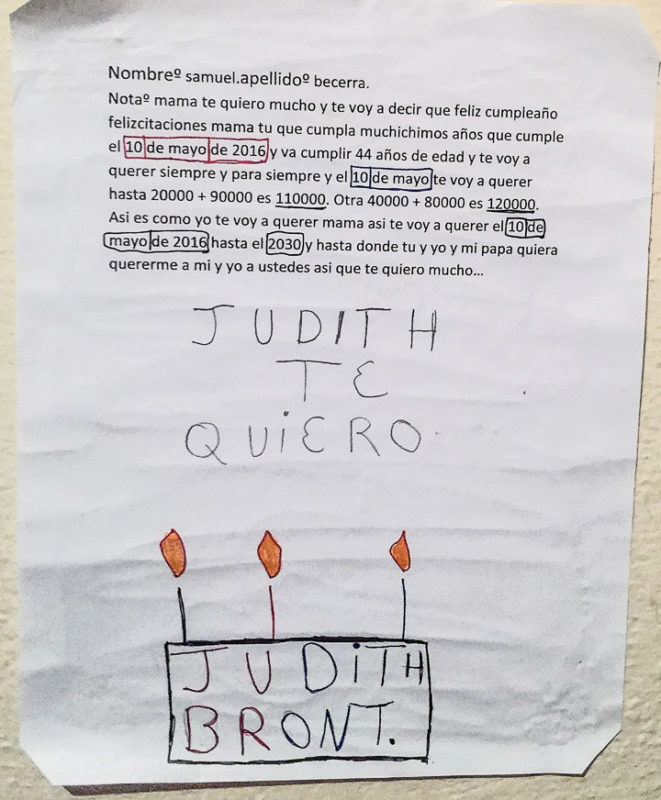

After marrying Giselo Bront, Ascención quitted her job at the factory, but she would still try to make some money. She dedicated to making food and pastries for sale, as well as selling clothes. The couple had four children. The oldest one was Judith Enoide, born on May 10, 1972. Judith’s childhood was spent in El Junquito, where she attended elementary school. She spend her middle and high school years between La Quebradita, in San Martín, where her family lived in an apartment, and 23 de Enero, where they moved later to a one-story house. Giselo built a second floor for his wife and children; and when the family grew, he built yet a third one. And it came on handy, because his eldest daughter would settle there when she married Miguel Angel Becerra, an event that would happen in a not so far future anyway, because they were very much in love, but it had to be celebrated earlier than expected, because she got pregnant.

Judith’s pregnancy went very smooth. “Everything was normal,” she says, while brushing her hair off her shoulders with a circular sweep of her neck. “We were very happy.” Problems began when Samuel was born. He didn’t cry. His weight and height were average, but he remained as silent as when floating in the amniotic sac. Immediately, he was rushed to the intensive care unit. He had a difficulty breathing, so he had to be transferred to Materno Infantil Hospital in Caricuao. His pulmonary insufficiency improved and he got stabilized in two days, but then, doctors noticed that in all that time, baby had not urinated. A renal ultrasound was performed and he was referred to the José Manuel de los Ríos Children’s Hospital, known as J. M. de los Ríos, on Vollmer Avenue in San Bernardino. Judith and Miguel Angel could not imagine that this place would become the usual scenery for both of them and their baby.

They sensed that something was not right, because people were moving around a lot, but whenever they asked they would hit a wall of secrecy from the doctors. Judith was focused on pumping milk from her breasts to feed her baby. When Samuel had spent four days in Nephrology Unit of J.M. De Los Ríos, where he had arrived when he was four days old, his parents were briefed on the situation. Their boy had an obstructed urethra and this caused hydronephrosis. His kidneys did not work. A week after he has surgery to relieve swelling. With the surgery, the hydronephrosis eased up, but his kidneys continued not to work. It was then when they put in his first catheter for dialysis. At ten days old, Samuel was diagnosed with chronic kidney failure and was condemned to dialysis.

“He was not urinating through his wee-wee, but through the tube that was connected to his back,” Judith explains. “And, of course, he suffered from incontinence. We should always put a diaper on his back.”

After one month at the hospital, he was discharged and they went home. As the child’s condition was so delicate, Judith had to undergo a special diet so her milk, which would be the only food Samuel could eat, wasn’t altered in any way. With the discharge papers, doctors also gave them an ominous prediction: Samuel could die at any moment, and even if he managed to survive for a short time, it was likely that he would never grow up.

They arrived at their house with a 7-pound newborn whose diaper was not wedged between his legs but rather surrounded him, making him look like a pie wrapped on blotting paper.

“In two months we became experts,” Judith says. Her eyes fill with tears, but the coffee shop where we are interviewing her has no napkins. She uses her fingers to masterfully wipe her tears. “My mother helped us a lot, especially to bathe him… with the Foley catheter.”

When they returned to the hospital for control, Samuel was a chubby baby with big cheeks. Doctors were surprised. Each month they had to go there. After a year and two months, he underwent surgery for the second time, now to correct the deviation, which allowed Samuel to urinate naturally.

“We had a party at home,” Judith says. “Samuel had urinated!”

Until Samuel was a year and a half they controlled his condition through diet. But from that age on they would have to administer Samuel with peritoneal dialysis at home (they would learn how to do it). We are talking about a procedure that takes 12 hours.

“Social Security Institute gave us the machine and we would do it at night. It was complicated, but that gave him a normal life and Samuel developed very well. We did not have anything resembling a nightlife. Wherever we were, we had to run to be at home before 8:00 pm, when he needed the catheters put in to be plugged into the machine. We set up a room like a hospital, just for the bed, the machine, a sink and a TV set. We were a team, both wearing masks, while I would prepare the solutions and catheters, his father would disinfect the room. The first time it took us two hours, but in a couple of weeks we would get everything ready in 25 minutes. We got strength just by looking at him. Samuel was not troublesome. We always set limits. We let him know that he had a condition and that he should be very careful. He was independent, disciplined, organized and serious. He never threw tantrums. For example, he could not drink a glass of water. Never. He could only have sips. We had to be careful so he would not go beyond his limits. It was a fight, but we succeeded. It was a group effort”.

At age 4 they started getting him ready for a kidney transplant. Around that time he went from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis, which had to be done three times a week in the hospital.

“On December 16, 2012, at 3:00 in the afternoon,” Judith recalls, “they called us to tell us that there was a kidney. They would do the transplant. Samuel had a lot of hope. On December 17, at midnight, he was taken to operating room. At 6:00 in the morning the bleeding was unstoppable. He was transferred to intensive care unit and when he came out he was almost dead. The urologist was leaving for Christmas break and as he said goodbye, he told us he did not think our son would survive. When he returned in January, Samuel was running around the halls of the hospital.

Samuel was 7 years old when they tried to do the transplant. His two kidneys were removed… and the attempt failed. He would never urinate again and could never drink more fluids either. Never again. His condition got much worse. It was hard for him to accept his reality, but eventually he did. His skin was very dry and his grandmother would apply oils to moisturize it. “It was not easy for anyone,” says Judith. “Neither for him nor for us, but he was enduring the worst part. At least, we could drink water.”

Five more years of hemodialysis awaited him.

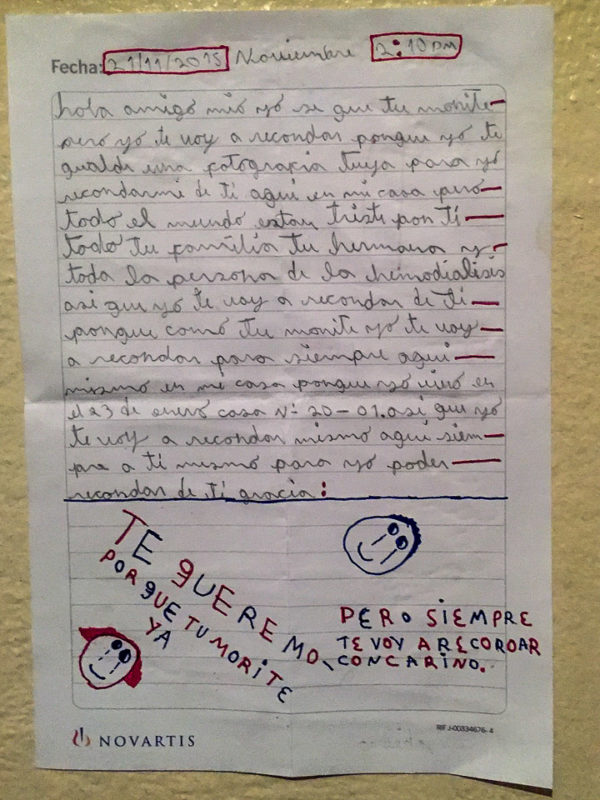

Amidst all this situation, Samuel would attend school like any child. He was very strict with his homework. In fact, he spent more time with his notebooks than his classmates, because he liked writing a lot. He confessed his dream to his mother. He would be a writer. But we could agree he already was one, since he could turn the pain into words and he had learned to deal with a writer’s solitude. He was a responsible person. He only would miss classes when he was hospitalized, which happened very often. He began to endure recurring infectious processes; and many times, the hospital did not have catheters of his size, which would cause new infections. There was a time when his life depended on installing of a catheter in his heart. Doctors warned us about the many dangers of that procedure, but he also recovered from that. Of course, after six months, that catheter got infected too. Amidst a thousand complications, Judith and Miguel Angel managed to get this heart procedure six times for Samuel. Last time occurred after doctors told parents they would not do it, because they were certain that the child would die in the operating room. Around that time, medical supplies were beginning to be scarce in hospitals; they were required to buy many things, difficult to get, but they managed to get everything. The refusal persisted, then the parents even went to Miraflores Palace, and appealed to the Council for the Protection of Children and Adolescents…

“Actually,” Judith recalls, “we force them to take him into the operating room. They put in a catheter that extended his life for a year, after which it became infected. He would have high fevers.

In March 2017, one month after turning 12, Samuel was hospitalized to get antibiotic treatment. Judith realized that the 9 children who were with their son on hemodialysis had fever and the same symptoms. In less than a week, 18 (out of the 25 who underwent this treatment during different shifts) were also hospitalized. But the hospital did not have antibiotics. The relatives of the patients had to try and find them… in a country where there were no antibiotics.

“That time was different,” Judith recalls. “They had joint pains, chills, extreme exhaustion.”

After a lot of inquiry, patients’ mothers were told that osmosis plant had not been serviced for months. They sent letters to the authorities. To all. They made complaints. They protested. They blocked streets … and when they returned to the hospital waiting room, they listened to their children screaming in pain.

“They were still receiving hemodialysis, but only for two hours. Samuel required four. There were no supplies. There was no water in the hospital (they had to bring it in water wagons). Samuel could not walk anymore. All the kids lost a lot of weight. They had contracted Klebsiella bacteria. Raziel Jaure, 12, passed away in early May. The kids were administered expired antibiotics and supply was very irregular.”

On May 10, on Judith’s birthday, she and her son ate a piece of cake in the hospital room and around 10:00 at night they went to sleep. At midnight, Samuel woke his mother up. He felt very sick, he wanted to go to the bathroom. Judith called the doctor on duty, who measured his blood pressure and suggested him to lie down in a different position. Then, he fell asleep. Doctor called the intensive care people, who came to the room and tried to reanimate the kid’s body. Throughout his life, Samuel was taken to operating room twenty times. Not without reason his chest was tattooed with scars. Judith thought that this time, they would mock fate again.

But it didn’t happened.

—Doctor told me my son had passed away – Judith says -. I stayed with him in the room. Holding him. Pain and anger were indescribable. I felt very impotent. I still think I could have done more… someone should have done more. I have tough memories on my mind… but those are the most beautiful ones. Samuel was the kid I always wanted to have.

—Samuel visits me in my dreams. He tells me he’s doing very well. The night he passed away, I fell asleep and I saw him. He told me: “Mommy, look! I don’t need the wheelchair anymore.” I understand he’s not suffering now, but I want him here with me. In 12 years, we only got apart that night…

Translation: Claudia Arteaga-Hung

This story is part of the series Las madres del JM, developed in partnership with the NGO Prepara Familia.

3326 readings

Milagros Socorro is a Venezuelan journalist and fiction writer.