A photojournalist traveled with a reporter, from Maturín, capital of the eastern Monagas state to the Luis Razetti hospital in Tucupita (capital of neighbor state of Delta Amacuro, one of the three Venezuelan states in which population is a majority native Venezuelan indigenous) for a news coverage. While waiting for the reporter to finish his work, a woman caught his attention. Inquiring about her, he learned that her name was Gladys, than she was 54-years old and has lived in that hospital all her life. So he went on to write her amazing story.

Pictures: Luis José Boada

Pictures: Luis José Boada

I never leave home without my camera. Experience has taught me, in a thousand ways, to be always ready. Stories always find a way to be told, and you just have to be at the right place and the right time to find them. And that’s how destiny wanted my camera and a woman with a unique history to meet at a hospital in Delta Amacuro.

I had to travel at dawn to arrive at a good time. It’s almost a three hours trip from Maturín to Tucupita and I had to arrive at the Luis Razetti Hospital Complex in Tucupita before 9:00. I took a colleague with me to take some photographs of an undernourished child who was hospitalized there. From very early, a journalist from the region, José, was waiting to help us get inside the hospital without problems.

We arrived to pediatrics and went up to the second floor in search of the child. We found him and I left my partner taking his photos. While I waited, I went to walk around the corridors with José, but with caution; if the Bolivarian militiamen found us with the cameras, we would be in trouble. Their “job” is to prevent reporters from showing the devastating truth about what’s really going on in the public hospital system and there is always the risk of being caught and get into troubles big time.

There wasn’t anyone in that corridor, only a woman with a slow and clumsy walk, and with a clear mental problem. I asked José who she was and, in response, he asked me if I had seen the movie La leyenda (the legend) of 1900. I didn’t, so he began telling me the tale of La leyenda del pianista en el oceáno (The Legend of the pianist in the ocean), which is the title in Spanish of the Giuseppe Tornatore’s film. It’s the story of a boy who was born on a cruise ship in the year 1900. He grew up on the ship and became a great pianist, but he never got off it. He never laid a step on land. The pianist died when the ship that had become an old scrap was exploded to sink it after the Second World War.

Pointing to the woman, José told me:

-She is like that pianist. Gladys was born in the hospital and has been living since she was born, 54 years ago.

I walked after her, slowly while I took my camera out of the bag. I felt the need to take a picture of her. I had before me someone who had spent her entire life in a hospital. Not even a jail prisoner spends so much time in one place.

I began taking photos very carefully, I didn’t want to scare her and I had to avoid being found. She seemed to be comfortable with my presence. I kept smiling, as if we already knew each other. We walked through the hall and entered several rooms. In some, patients were lying on their beds and everyone greeted her with affection. She took me around as someone who shows her home to a visitor. And that’s how it was: Gladys was giving me a tour around her house.

We entered a lonely room. Inside there was a baby pen, and I noticed that her face changed. She was not laughing like before. She walked towards the window and stared at the street for a few minutes. I didn’t say a word, I just kept taking photos.

She moved away from the window, laid one of her hands on the metal pen, as she looked at the camera as if she wanted to tell me something.

At that moment I asked her the first question:

-How old are you?

-19 years old-, she said haltingly and aloud.

Gladys rarely speaks, her mental problem hampers her from communicating properly. We continued touring around every corner of the second floor of the pediatric area and went in a very small room, and inside there was a stretcher covered with a red blanket, also two bags with some rags and plastic pots where she kept some food. I asked her if that was her room, and he nodded. I told her to show me how she slept, but she refused to tell me and left.

She left me alone in her room. I watched every detail, trying to imagine how someone could bear looking at the same walls for more than half a century. I went looking for her and I bumped into my photographer friend, who had already finished doing his job, so I said goodbye to Gladys. But before leaving, I asked a nurse if she had always slept there, she said no. Her original room was located on the second floor of the internal medicine area, but after a fire in the ER, she had been moved to a room in pediatrics. I putted away my camera and headed back to Maturin.

During the trip I did nothing but talk about her. I needed to know more. A story like that could not be summarized in a few pictures. I did not know anything about her life, I only knew where she had lived since her birth.

I went back to my routine but I could not get Gladys’ story out of my mind. I told it to everyone. The more I talked about her, the more I became curious. I had to investigate. Then, two weeks later, I returned to Tucupita in search of answers.

And obviously, for new pictures.

It was 8:00 o’clock in the morning and I was already arriving to the city again. There were problems with public transportation and two older women asked me to give them a ride. Although I was in a hurry, I decided to bring them closer to downtown, where I had agreed to pick up José. On the way I asked them if they knew Gladys and they told me that everyone in Tucupita knew her. It is a small city, of about 85 thousand inhabitants, surrounded by 3,500 streams of the Orinoco delta, territory of the Warao ethnic group. Gladys could not see the river from any of the hospital windows.

Before they got off I asked them if they knew anyone who could talked me about her and one of the women told me:

– I know of a retired nurse who knew her very well, her name is Alcira Salazar, but I do not have her number. I only know that he lives in Palo Quemao.

I wrote down what I could, and before getting off, the woman told me:

-I think she got her tubes tied because once she had an abortion -and she closed the car door.

I lowered the window of the front seat passenger and asked:

—How come she had an abortion?

– Yes, but I can’t say if it’s true. Ask at the hospital.

I picked up José and we headed to the home of a nurse with whom he had arranged an appointment for an interview. I could not believe how Gladys could become pregnant. If it was true, someone must have abused her. And what had happened with the child?

We arrived at a very humble house and we were greeted by an elderly woman, who invited us to come into the living room. Her name was Cleotilde Mejías, 82 years old and who had worked 30 years in the hospital. We began talking about Gladys. She told me that she met her when she was a little girl, but that she wasn’t there the day she was born. That the nurses took turns taking care of her, that they all loved her very much, that they looked out for her things. And that she was fond of Christmas, it was December the month in which she looked happiest.

She told me how she placed her in a bed in the nursing restroom when they were on call. And since she was a child, she laughed at everything.

-She was my companion many nights, – she told me with some nostalgia-. She was very affectionate, despite her mental disorder. She was not violent. Every day she visited the patients and knew the illness of each of them. She pretended to be a doctor!

I asked her about the abortion and Cleotilde assured me that Gladys had become pregnant when she was very young. She did recall what was her age at the time. Maybe between 15 and 20 years, she told me.

– And who was the father?

She replied that at the time everyone suspected a stretcher or a policeman who worked at nights. At that age, Gladys used to walk the second floor of internal medicine throughout the day and night. They became aware of her pregnancy, at her third month. Nobody inquired anything. Everything suggested it was the stretcher, but the truth was never known.

Cleotilde told me that she had a bad head, and she did not remember many things. She believed that Gladys’ child had died, but she could not tell, since she was at leave when Gladys gave birth. And she knew that the doctors had decided to tie her up because, with her innocence, someone could abuse her again. I thought that talking to her could clarify my doubts, but since that was not the case, I decided to go back to the hospital.

I went straight to the pediatric area, went up to the second floor and began looking for her. I did not see her in the hallways and I went to her room, but it was empty. I went looking for a nurse and asked if she knew where Gladys was. She told me that she had been moved to the second floor of internal medicine, where there actually was the room where she had slept since she was a child.

That day there the place was packed with soldiers. To access the second floor, José and I had to go through a very large room full of patients. A guard stopped us and asked where we were going. José replied that we were looking for a doctor for an interview. He let us through, we went up the stairs and reached a very long corridor.

At the end of that corridor, I saw her.

She was standing up playing with a thread. I greeted her with my camera ready. I had to take the pictures very quickly because I was worried that they would spot me.

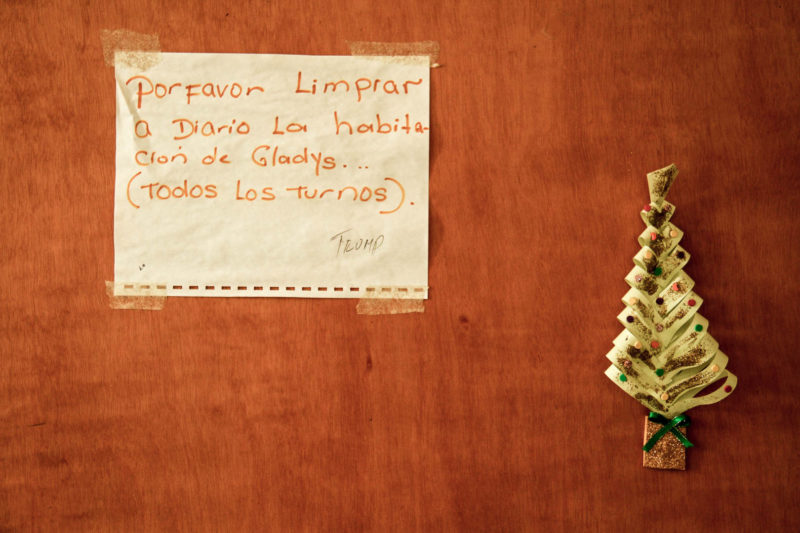

I asked her which was her room was and she pointed it out with her hand. I saw that it was the number 9. There were 12 rooms in the hall. In hers there was a larger bed with a very worn mattress. At the door, a sign read: “Please, clean Gladys’s room every day (all shifts)” and it was signed “Trump”. I tried to take as many pictures as I could. I wanted one of her with a nurse. I told one of them to ask her how old she was, and she replied, “19”. I took advantage of the fact that the nurse was right at the door of the room and I took a picture of her.

But I kept looking for the picture of her lying down. I tried to convince her, but she refused. Then she went out into the hall and José told me we should go. I said goodbye to Gladys, I told her that it was a pleasure meeting her and I left.

Arriving at the staircase I realized that I had left the camera bag in the room.

When I went back, Gladys was lying looking through the window. I was able to take the photo I was hoping for. In that moment I realized that it was most likely that I would not see her again. But even so, I was determined to tell her story. Gladys never goes down the stairs. She spends all day walking and visiting patients. The internal medicine area was for her as the boat of the pianist of the movie.

I sought to speak with other nurses. One of them assured me that the child was born, but she was not sure if anyone had adopted him. They also mentioned the nurse Alcira Salazar, the same one that I learned about from one of the women I gave a ride when entering Tucupita. There were several accounts about her pregnancy, but all pointed that it really happened.

I left the hospital determined to find Alcira. After asking a couple of times about the sector where she lived, I arrived at her house. A 73-year-old woman came out to meet me, she walked aided with an old cane.

-How I miss my little crazy girl. She was like my daughter, – she said, and began to talk.

Newly born, Gladys was abandoned in a wooded area. She was found by a peasant when attending his crops. She was covered with ants, almost dead. The man heard a weak and choked weeping in the brush. He took her to the hospital and since then the nurses took care of her.

When Gladys became pregnant, she locked herself in her room. She did not walk as always down the hall. Alcira told me that when she found out, she went to visit her. Gladys was already three months pregnant. She felt guilty for not giving her enough protection, but she has been away for several months for a medical leave when the rape happened. Everyone trusted that no one would be able to hurt her, but they were wrong.

The child was born with health problems. He was in an incubator, but died a few days later. He was a “catirito” (blond) child, and the stretcher that everyone suspected was white. She believes that more could have been done to save the child. Alcira herself was determined to keep the baby. Several nurses also wanted to keep the child, but Gladys said her son would be for her mother Alcira.

Gladys was sad for many days. She leaned out the window and pointed to the morgue, she knew he was taken there. It is the same window through which she stares. When I asked how old Gladys was when her baby died, Alcira answered what I later found obvious: she was a 19-year-old girl.

A few years after the baby died, a newly appointed director of the hospital requested that Gladys should be confined to the Maturín asylum. And they did. Alcira said that she was tricked and taken in an ambulance. But when they found out, the nurses demanded to bring her back. A few weeks later, Gladys was in room number 9 of the internal medicine building. It is the only time she has left this hospital, and against her will.

-She was always my darling and always will be-, Alcira said when we said goodbye.

Back home, I could not stop imagining Gladys walking through the corridors of that hospital where I met her, amidst the rubble of what had been a modern and well-endowed institution, living unknowingly a delta version of Tornatore’s film. Both tell the same story of memory and oblivion.

Translation: Josefina Blanco / Edition: Luke Robert Blake

Note: This is a story of the Venezuelan website La vida de Nos. It is part of its project La vida de Nos Itinerante, which develops from storytelling workshops for journalists, human rights activists and photographers coming from 16 states of Venezuela.

4112 readings

I am 37 years old and I live in the city of Maturín. I am a musician and an attorney and, for the last 12 years, a graphic reporter. I have devoted myself to portraying with photos how I see my country’s life and reality.

2 Comentario sobre “The Clock That Stopped at 19-years Old”