Nine years after having migrated into another country, Roberto Costa returned to Venezuela to cast his vote in the presidential elections of July 28, 2024. He reunited with his mother, a migrant herself, who came to vote too, and with his uncle, the only family member still in the country, who lives in the house they all left.

PHOTOS: MARÍA JOSÉ DUGARTE

PHOTOS: MARÍA JOSÉ DUGARTERoberto Costa was still in bed. He had been tossing and turning all night. At 8:00 a.m., he knew there was no use in trying to sleep anymore. How could he when he was so anxious? It was July 28, 2024. From the outside, he could listen to the online news program his uncle had tuned in to learn what was going on with the Venezuelan presidential election. He could also hear the clatter of pots and pans. It was his mother, whose ancestors were Italian, giving her all from the break of day making lasagna or, as we locals call it, pasticho. Because pasticho is a Venezuelan dish.

How he had longed for that day! The sounds, the scents, the Sunday lively atmosphere of the house he grew up in and the one he had had to leave a while ago now. There he was again. It was as if time had stopped. He left from Germany on July the 2nd and landed in Venezuela on the 3rd, sixteen hours and stopovers in Cuba and Turkey later. He had returned to reconnect with his city, but, most importantly, to vote. That’s why that Sunday felt like a make-or-brake, solemn, pivotal day.

He finally got up and had breakfast watching the news. At about noon, he left for his polling station.

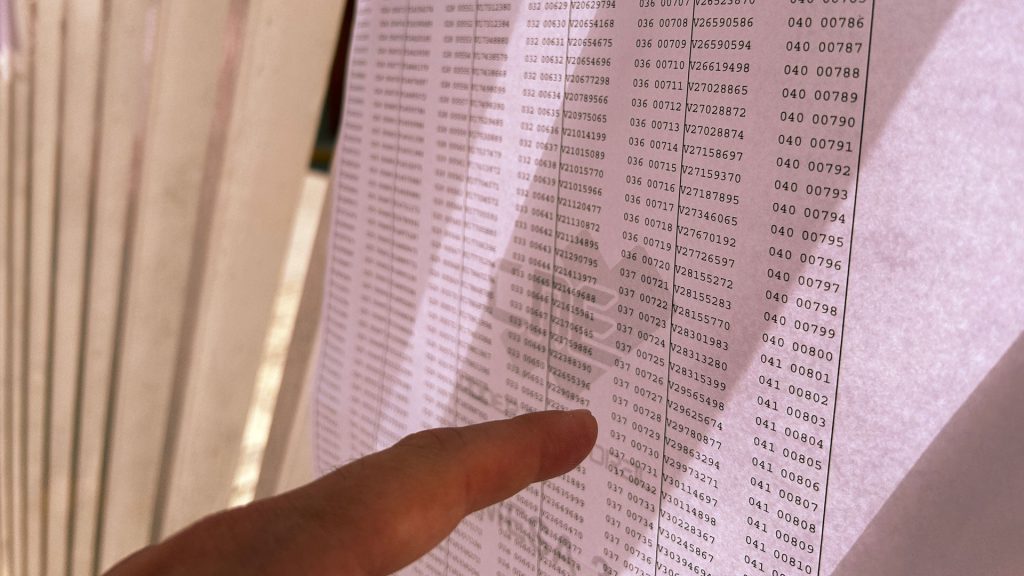

He walked head high, his chest forward. He checked his name on the voter list, located the ‘voting table’ or booth where he was supposed to exercise his right to vote, and just waited in line for his turn. It was a long line going around the corner. Some people who had arrived at daybreak were still waiting because, according to the military from Plan República that are deployed during elections in the country, there was something wrong with one of the voting machines. Apparently, they were working on it. But it didn’t matter to him that the line was moving slowly. He would stay put until he was finished, no matter for how long. Not even the scorching sun would make him leave.

Nine years is almost a decade. One could say that nine years is almost half a lifetime. Roberto had not walked the streets of his hometown for nine years. He left Venezuela in June of 2015, as if he were fleeing, just a few months after his graduation as a filmmaker from the National Film School. He was 24, hopeless, and fed up. He was sick and tired of the injustice, of politics, of the lack of solutions. So he took the word of a cousin of his who lived in Jena —a town in east-central Germany— who had offered him a place to stay, and hit the road.

He had not even been able to practice his profession. As a student, he had teamed up with his classmates to make independent films. However, whenever they tried to seek funding from state institutions for production, they were told that unless their material was about Bolivarian Chavismo, they would not get a penny approved. They managed to finish two projects because they somehow tweaked things so that the focus was on issues that ruffled no feathers. But they did not want to keep quiet anymore. They wanted to tell the stories they wanted. About a country. About its wounds. They all went their separate ways.

Roberto didn’t stay long in Jena. The town was kind of isolated, with not many jobs to offer. He moved into a small bedroom in Berlin and got a job at a McDonalds. It was the first job of his life. He didn’t feel comfortable in the food chain uniform and had a hard time tending to customers. As he was still not fluent in German, he couldn’t take the orders properly. Even his co-workers made fun of him.

But one day, they invited him to a party. That night, Roberto asked someone to dance to the rhythm of salsa and let himself go. He was the life of the party. They began to see him as someone fun to be around and were nicer to him. He made friends at that McDonalds and stayed there for two years.

He left to work on his career. In all that time, he had not stopped dreaming of writing, producing and directing audiovisual material. He turned into a nomad, moving from one country to another. He went to Argentina: first to Salta, where his mother had migrated, and stayed with her for a long time; then to Buenos Aires. But he was facing the same problems as in Venezuela (inflation, exchange control, etc.), so he crossed the Atlantic again. He moved to Parma, Italy, and then to Madrid. Although he couldn’t find a stable job in the places he went, he was grateful for some of the opportunities. He worked as an actor for TV, and pitched some ideas to independent production companies and got involved in their execution. He ended up returning to Berlin, where he worked as a barista, as a pizza maker, and, in his spare time, on the occasional screenplay.

In that wandering about, hither and thither, as he struggled to find his place in the world, he tried not to think about Venezuela. Sometimes it’s better to forget about those scars, he thought.

One was his grandmother. Her name was Aida Lamus and she was once the president of the National Securities Commission, serving during the Rafael Caldera and Hugo Chávez administrations. But she was forced to retire because she opposed the so-called Bolivarian Revolution. She was sad, very sad.

An oil strike took place in the country a year before that, or after that —he was a little kid and does not remember. Those were happy days because he played a lot with his little cousins, for were closed, but he also noticed the gloomy expression on many adults’ faces. His uncle, who worked at the state-run PDVSA, was fired and had to leave the country.

That’s how the family home started to empty out. A house with four bedrooms, two living rooms and a large garden was too big for an only child whose cousins were like his siblings. They all left. And only his grandma, his uncle, and he appeared in the family photos. And the puppy.

Before long, the empty house was haunted by the insecurity around. And he was afraid of going out. Some of his friends and schoolmates had been kidnapped while in their own homes or robbed at gunpoint. Roberto was also a victim of crime in 2010, when he was shoved a gun to the face by a robber.

Even so, his family and his home were still his bubble. Roberto was a privileged kid and wanted for nothing. He practiced horseback riding, had a club membership, and traveled the world. But as soon as he entered college, he realized that the country had gone over a cliff edge. And the bubble that had shielded him got poked and he was now exposed to the elements.

It got harder and harder to buy food because there wasn’t any in the supermarkets. Humidity damaged the walls of the house, which they couldn’t afford to paint as often as they used to. Services such as electricity and water worked intermittently, and power and water outages were a common occurrence. His friends began to leave the country one after another. Until he himself packed his bags that day in 2015 and landed in Germany.

Shortly thereafter, the puppy died.

And Grandma Aida passed away too. He had to grieve her death and cry for her from miles away.

In the house where he grew up, only Uncle Julio remained. It was he who greeted and hugged Roberto at the airport on July 3, 2024 when he returned to vote. Time shows in Uncle Julio’s face, whom he found wrinkled and tired. On the way to Caracas, Uncle Julio talked about the changes in the city and pointed to the new constructions in Las Mercedes and to the newly opened restaurants. Roberto had a strange feeling stepping into his house: things were different but the same. His uncle had cleaned and painted the house, but it looked empty. He hadn’t been able to make it seem less lonely.

If Roberto was sick to death of everything when he left and had tried not to think about the past, why had he decided to come back?

It was not an easy decision foe him to look inside again. At first, he refused. In May, during one of the many casual conversations he had with his mom, she told him that she wanted to go to Venezuela to vote in the July 28 elections.

“I’ve got a feeling this time it will be different.”

“For real? Are we playing democracy now, Mom?” he replied.

She gave him her reasons. “Why, of course, Roberto. It’s worth the effort. Every vote counts. We must seize this opportunity. We must rescue the country.” He kept thinking about her words. In the end, she won him over. Roberto even came up with the idea of making a documentary about his return after almost ten years to show how Venezuelans lived the electoral process. He was thrilled to see María Corina Machado all over social media touring towns and villages. He himself got carried away by that infectious energy.

He went from total apathy to saying that he would come to Venezuela for him and for many of the 10,000 Venezuelans who live in Germany who wouldn’t vote because they couldn’t have their place of residence changed, or their passports renewed, which were among the many obstacles the National Electoral Council had put in their way to register.

Weeks before setting foot in the country, Roberto chatted via WhatsApp with the few friends he still had here. He asked them what they thought about the political situation in the country, and whether or not they were going to vote, and almost all said:

“No, we are not. You know that they are going to steal the elections, don’t you? They’re going to fuck us all.”

But when he arrived, he saw they were eager to participate. He noticed the same energy in the streets of Caracas. He went downtown. He talked to people and recorded many on video. Some asked him to blur their faces for fear of political persecution. Others talked to him about their experience by voice note only. Many refused. He could feel the fear in their eyes and words, but also their willingness to take part in the process.

He noticed that people were in a rush and a on the edge, that the public transportation system had deteriorated, that things cost an arm and leg; and yet he couldn’t help but be moved. Listening to what people had to say, waking up at home once again, taking in the colors of the city, it all made him consider something that had never crossed his mind: What if he stayed. What if he came back and settled to bear witness to the rebirth of the country.

The idea of staying in Caracas also resonated with his mom. She too had returned to vote. She arrived a few days after Roberto, who greeted her at Maiquetía with a hug. Candy, the puppy they had adopted in Salta, hadn’t stopped growing.

Time seemed to pass very quickly at his polling station as he listened to people’s conversations and played video games. When his turn came, he stood in front of the voting machine, confirmed his choice on the touch-screen, and checked the paper ballot slip several times and dropped it in the ballot box.

On his way out, he saw his mother, who was just watching:

“Now we’ll have to wait and see what the fuck these guys come up with,” he told her.

He went back home with her and a friend who documented the scenes at the polling station. They couldn’t stop talking about the elections, about the possible scenarios. At lunch, as they ate the pasticho with an ice-cold glass of Pepsi, they watched the news on YouTube.

“I think this time we are going to make it.”

When it was Roberto’s mom turn to vote, the line was shorter and she was home in no time. Internet was slow or down during the night, and Uncle Julio set up an antenna to watch the results on a local TV channel. Just after midnight, on July 29, they heard Elvis Amoroso, the head of the National Electoral Council (CNE), read the first bulletin. He claimed that the system had been hacked, that Nicolás Maduro had secured 5.15 million votes, and that Edmundo González had gotten 4.45 million votes.

Roberto and his family just lost it. “Fraud, fraud, fraud!” they yelled. Roberto turned on his camera and recorded the silence of the streets. There was no celebration. That night he couldn’t sleep either, looking for news and reactions from the opposition. He felt he had to do something. He also feared that people would not dare to go out. But a few hours later, he saw videos of people from Petare, Catia and other areas who had taken to the streets. He tried to get there to shoot the whole thing.

The next day, he made an effort not to watch the news, but he just couldn’t. He did nothing but search for information on social media. He read all of Maduro’s statements, and watched excerpts of the ceremony where Maduro was declared victor by the CNE. He couldn’t leave that scene out of the documentary.

He also learned that the flights to Panamá and the Dominican Republic had been cancelled, and is grateful that his return flight is with a Turkish airline. He is concerned about his mother, though, because she will have to make a stopover in one of those two countries if she decides to return to Argentina.

They haven’t bought their tickets yet. They still don’t know what they will do. In silence, they’re still waiting to see what happens.

“You’re more than welcome in Berlin if you don’t want to deal with this shit for six more years,” he tells his Venezuelan friends.

5229 readings