One day, in early 2018, Keyla, a 14-year-old pregnant girl, arrived at a hospital in Barcelona, in eastern Venezuela. She was all by herself, running a fever and leaking amniotic fluid. As soon as she was performed an ultrasound scan, the doctors knew that her baby had died. Dr. Nathali Arismendi, at the time an OB-GYN trainee, was amongst those who attended to her. Unknowingly, that young patient would teach her a lot.

ILLUSTRATIONS: WALTHER SORG

ILLUSTRATIONS: WALTHER SORG

I once heard from an old and wise professor that to be a physician one had to fill two little bags that one would carry over one’s shoulders. One, he said, was that of knowledge, which was gained through study and practice; the other was that of experience, which, he insisted, could only be gained through observation and the patience that the years teach us.

It was he also who said that the death of a woman is not only the death of a living being: women have no ending to them; they are wives, daughters, sisters, grandmothers, friends and mothers.

There have been times during my professional practice where I have been reminded of those words. For example, that time when a patient, who was barely 14, crossed paths with me and my colleagues and taught me a lesson. She was one of the many patients who came to the delivery room of that hospital in Barcelona, State of Anzoátegui, in eastern Venezuela, where I was completing my residency as an obstetrician and gynecologist.

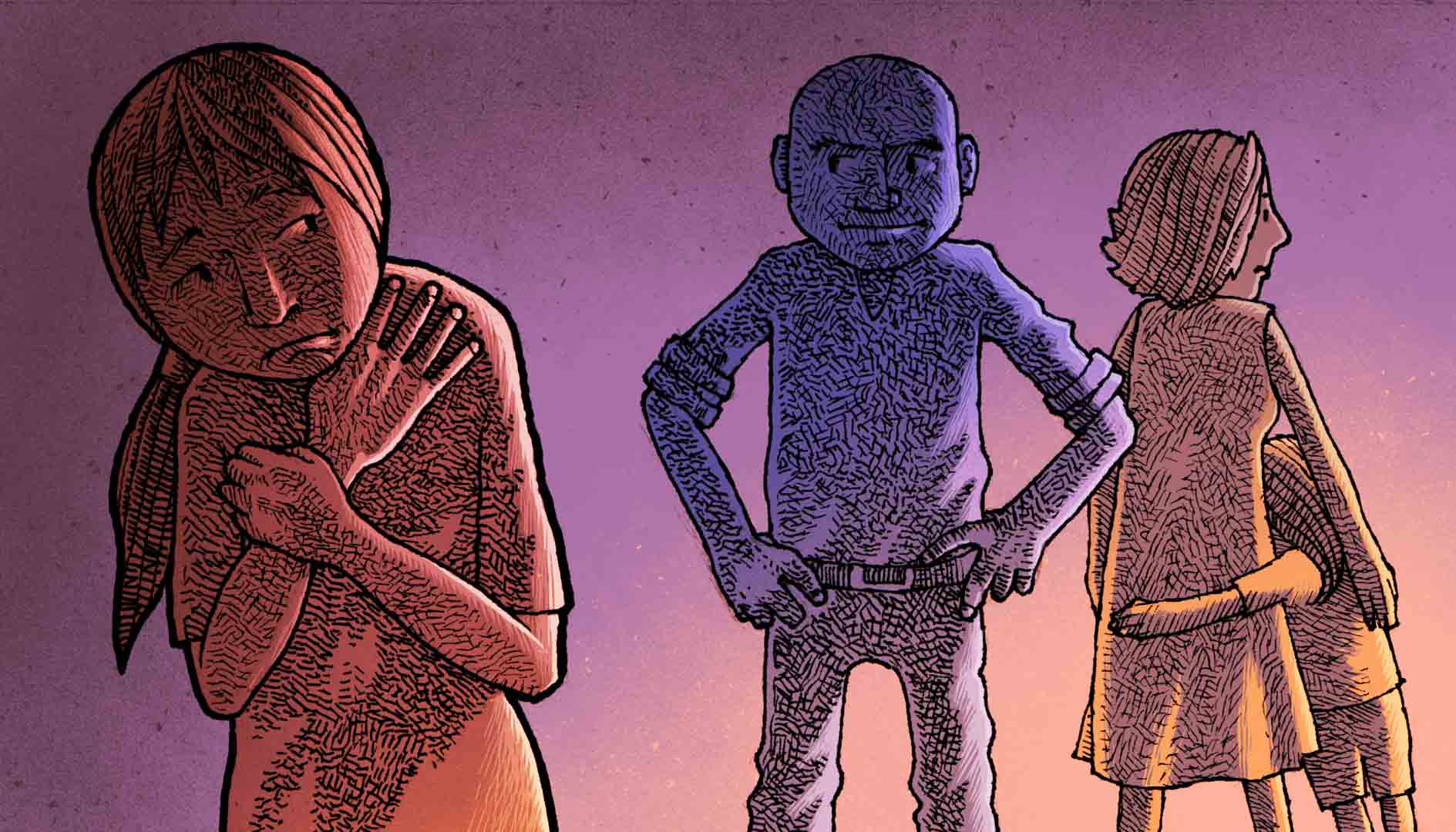

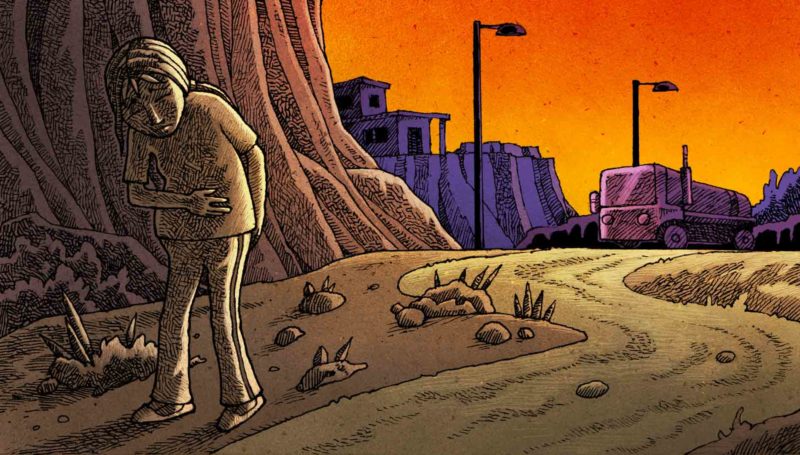

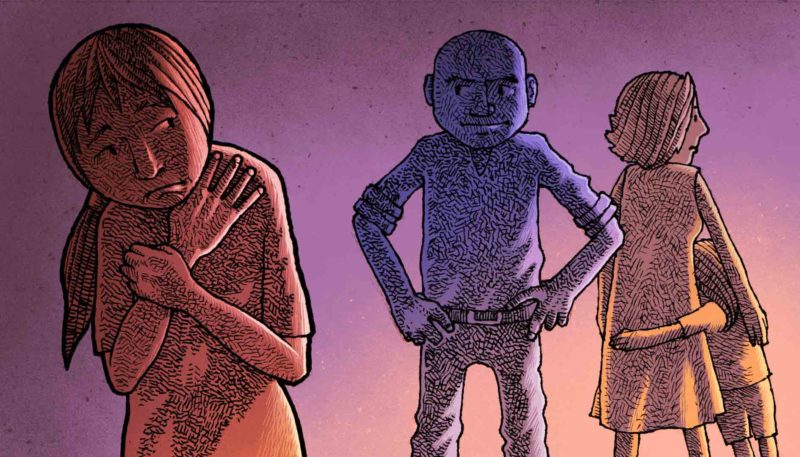

Keyla was too young to be a mother. She was also way too young to die. She was 14 years old when her stepfather got her pregnant. She lived with her mother, her stepfather and her little sister in a small hamlet. When she arrived at the healthcare center, she was emaciated, ashen and running a fever; her eyes seemed to be melting under dark circles and she looked like she had been crying. She had been leaking fluid for almost two days. She was in pain. She couldn’t feel her baby. When we asked her why she never had prenatal care, she didn’t answer, but then she told us that she hadn’t taken any medication because she had no money.

It was early 2018 in Venezuela, and the hospital she had arrived at had nothing, not even a syringe to administer an injection. At times, we doctors had to examine patients in unsanitary conditions because, more often than not, there was no running water, no disposable paper sheets for stretchers, no gloves to wear, no bleach to wash the floors, and no soap to wash our hands.

Keyla sat there for about ten minutes, quiet, without complaining. She looked so weak that I decided to keep a close eye on her. When her turn came, we laid her down on one of the OB-GYN gurneys in the emergency room and proceeded to examine her. The young woman was so short that she could barely climb onto one of the large OB-GYN stretchers known as ‘donkeys’, which have been designed for use with adult women.

Keyla told me that she had arrived all by herself. She also told me that she had walked for half an hour but that she was in such a bad shape that she got on the motorcycle of a stranger who passed her on the road and was kind enough to take her to the hospital.

My colleague inserted a speculum and checked whether or not her amniotic membrane, that which holds and protects the baby, had ruptured. She was then performed a vaginal exam and we noticed that her cervix was just slightly effaced, that her hips were too small, and that, should the need arise, we would not be able to induce labor. We didn’t know exactly how many weeks into her pregnancy she was, as Keyla had not had an ultrasound performed and could not remember the date of her last period.

We took her to the ultrasound room and started a series of measurements. Our estimation was that she was approximately 39 weeks pregnant. We also noticed that there was no amniotic fluid surrounding the baby, and that the baby’s heart was not beating.

We discussed the case with the specialists and decided to admit her, put her on antibiotics and take her to the operating room to perform a C-section as soon as possible.

That was the beginning of what we doctors call ‘the odyssey of the on-call physician.’

Finding the medical supplies we needed to operate on her was an obstacle course. She arrived at the hospital alone, so there were no family members to ask for stuff, no blood for transfusion should she need one, and no antibiotics —the few vials available were reserved for ‘serious emergencies’ only and we needed the authorization of various service coordinators and that of the director himself by phone to use them.

We started calling him, but he didn’t answer. After a while, at about 11:00 p.m., he authorized us to take two vials only. We injected them on Keyla, administered her some kind of hydration, and took her to the operating room.

We performed the C-section and delivered the baby. Apparently, the baby had been two to three days with no vitals, was affected with necrosis, smelled bad, and was warm to the touch, as was the patient’s uterus. We cleaned the entire cavity with a saline solution to try to curb the infection, and decided to close her and put her patient under observation to monitor her vitals.

When she was more alert, we explained to her what had happened to her baby.

She listened quietly. She refused to see him. She didn’t shed a tear.

The rest of the night, she remained in a more stable condition as she slept on a bed that had no sheets. A patient gave her some sanitary pads to contain the blood gushing out of her, and we put her on pain and fever drugs.

The next day, I was still on call at the ward. I peeked in to see her and we gave her some of our water to drink and asked her if someone was coming to bring her food and clothes. She said she doubted it. We asked her for a phone number to contact her mother, but she said nothing. We asked her for some personal information to see it the social service unit could provide her with assistance, but only as a matter of ‘standard protocol’, because we were used to never hearing back from them.

The fever would not go down. We were worried because, apart from those we used for the surgery, we hadn’t been able to find more antibiotics to give her, let alone at the prescribed times. We did what we needed to do: write down in her medical chart our instructions and suggestions for her to recover, based on her case. Needless to say, there was no guarantee that they would be followed.

It was during those months, at the beginning of 2018, that the shortage of drugs and medical supplies turned into our worst headache. We are talking here about a tier 4 university hospital and, in this case, the largest in Anzoátegui and the one where the most serious cases from other cities were sent to. Since the other healthcare centers had nothing to treat patients and counter-referrals were not permitted, virtually all the cases were taken to our facilities. The thing is that we had nothing to work with either. The few supplies we had were not enough. The shortage of medicines was more than apparent in the nearby drugstores, and not all patients could afford to buy there anyway.

We didn’t know what to do with Keyla. When we realized that it was almost 4:00 p.m. and she had had nothing to eat, we got worried; so, doctors, nurses on duty and two patients with whom she shared the room managed to give her two arepas and some cookies. She ate heartily, and of the little we had offered her, she save some ‘for later.’

As the days went by, it gradually got easier for her to talk to us.

She told us that her mother was not going to show up because she feared that, in light of what had happened to Keyla, they would take legal action against her for having allowed Keyla’s stepfather —who was also abusing her— do that to her, and that they would take her little girl away from her. That was also the reason why she refused to take Keyla to the hospital. Keyla told us that she wanted to be a teacher, that one of her neighbors had taught her to read and write because she had never been to school, and that that had always been her dream. She expressed her concern for her little sister, who was still living under the same roof from which she had fled.

She told us that she didn’t want to become a mother yet. That she wasn’t ready.

Three days passed and she hadn’t been given the medication she needed. Her temperature got higher, her wound began to ooze pus, and her vital signs were suggestive of her deteriorating condition. We consulted with the specialists and decided to take her back to the OR to cleanse her again with saline solution to try to mitigate the infection… and feel like we were doing something to help her. While we waited for the antibiotics to appear, we found some of the surgical supplies.

When we opened her up, the whole site was infected. There was so much pus in her abdominal cavity that her viscera had glued together and her uterus was changing color to black. We decided to remove it to eliminate at least another focus of infection. It was with a heavy heart that we performed a hysterectomy on a 14-year-old girl. She would no longer be able to have babies.

We hoped she would show some improvement.

A few days went by and we kept watching over Keyla. Since her family never showed up, we created one for her at the hospital. We doctors made it a habit to ask about her condition as soon as we arrived, kept a close eye on her condition, and brought her food from our homes —because the hospital gave out none— and some clothes and the few personal hygiene items we could buy.

She was not getting better. There was no way for us to perform the tests she needed. We decided to give her whatever antibiotic we could find so that at least she would get some. It was what we called ‘a cocktail,’ virtually a placebo, because the fact is that she needed stronger antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, meropenem, vancomycin or ciprofloxacin. Any of them, whether it was the few vials that arrived at the hospital, or the tablets we could find at our homes, or those that other patients didn’t need anymore. We no longer cared if they were different names, or if we didn’t give her the right dosage at the right hours, or if they were past their expiration date (even if we knew it wasn’t the right thing to do). She needed them and we had to try our best.

Nevertheless, we didn’t succeed in making her any better.

On day 12, we decided to operate on her again. As she was already familiar with the procedure, she lay down on the operating table while she waited for the anesthesia to be administered. There was a moment when she grabbed me by one hand, much to my surprise, and looked at me and said:

— “Please, don’t let me die!”

I smiled nervously and reassured with a poker face. “Don’t worry. I’ll see you when you wake up; you’re going to be fine,” I replied.

When we opened her up, we saw that the infection had gotten worse and that almost everything inside had necrotized. There was not much more we could do. We tried to cleanse and suction.

In seventeen minutes of surgery, she went into cardiac arrest twice.

She didn’t make it.

But life in the hospital went on.

I have seen many patients die in the course of my career. Few people know it, but we are taught to become desensitized to death, or at least to hide our feelings. Sometimes we become attached to patients that we had known for a while before they pass away. Hers was just another death. But she in particular was one of those patients who has made me reflect on the meaning of life, because she was very young and had her dreams to fulfill and wanted to fight and protect her sister. She was alive, she had a voice, she spoke to me, I tried to play God with her, I wanted to heal her and I made a promise to her. Fifteen minutes later, she was gone.

We are fragile, fleeting beings.

And we doctors are not a different species, though at times we forget that we aren’t. That day, as a physician, I experienced what it is to be only human.

Maternal mortality is often used as an indicator of a country’s development and living conditions. Maternal death is generally avoidable with adequate and accessible healthcare services and the conditions and materials required to provide obstetric care to patients. In Venezuela, the actual data on this and other important indicators typically overlap, and demographic yearbooks on maternal, perinatal and adolescent pregnancy mortality and morbidity are seldom updated. Even as an obstetrician, I wonder: if getting pregnant poses a risk of death even for those women who want to become mothers, what about those who didn’t choose to get pregnant in the first place?

Whatever happened to Keyla’s little sister?

That year, numerous wives, daughters, grandmothers, sisters, friends and mothers died. That year, countless women died in my country. And I say countless because I lost count of those who died while I was there. I do not know how many. Those are figures that many want to keep undisclosed. But lives are always much more than mere figures. Lives are dreams. Lives are names. Like Keyla.

This story was written within the framework of the “Narrative Medicine: Our Bodies also Have Stories to Tell” course taught to healthcare professionals via our El Aula e-nos online training platform.

519 readings

I am a Venezuelan GYN/OB who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine. I am an itinerant. I love my family. My life changed with the things I learned at a hospital. It’s no coincidence: I was born to help.