Minguito has the responsibility of keeping afloat Kiosko El Caney, a small business that his father started in Playa Parguito, Margarita, in the early ‘80s. The multifaceted economic crisis has compromised its operation, but nothing compares to the impact of the pandemic confinement.

On Monday, March 16, 2020, during a mandatory TV broadcast, Nicolás Maduro announced that the entire country would be placed under quarantine as of 5:00 a.m. on the morning of the 17th due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Jesús Domingo Boadas, also known as Minguito, finished watching the statement on the restaurant’s TV set; in such an uncertain context, one thing was clear to him: he had to close up shop. For the first time in the forty years since its inception, Kiosko El Caney, the oldest restaurant in Playa Parguito, in Margarita Island, would be closed for business.

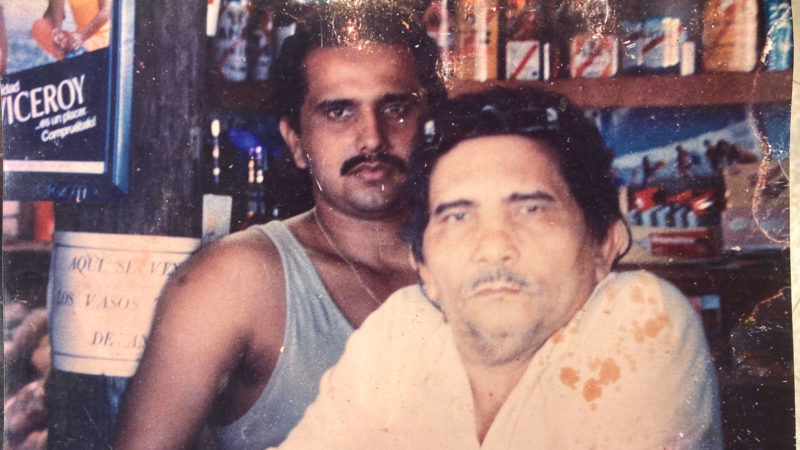

In the early 80s, Domingo Boadas, Minguito’s father, went on the weekends to a house his family owned on Avenida 31 de Julio, the road that runs from Porlamar to Manzanillo. Lying in his hammock, he would stare at the unspoiled landscape of Playa Hippie, as it was the name of Playa Parguito back then. He loved to watch the sea and the waves breaking loudly on the white sand.

But there was something missing for it to be perfect, he thought. So he decided to plant coconut and sea grape trees. Every other day, he would fill a couple of buckets with water at his house in La Asunción, load them into his pick-up truck, and drive to the site across a dirt road. Once there, he would take the buckets out of the vehicle, water the trees he had planted, and drive back home. He did so for two years, as he watched patiently —and tenderly, perhaps— the coconut and sea grape trees thrive and provide much needed shade.

People called it Playa Hippie because, at the time, hippies loved to go there to swim and relax. Domingo hired a woman who went there on the weekends to make empanadas for sale, and he would bring an ice chest cooler with beers. That is how he started his business. Two years later, he was running a Coca-Cola kiosk, one of the red stands that Coca-Cola strategically installed along the island. Hence the name of Kiosko El Caney.

The next step was to build the floor and walls. By the mid-80s, Kiosko El Caney was a restaurant with tables for customers and sun shades on the sand.

As time went by, the hippies turned out to be wave runners who made Playa Parguito one of the most visited beaches by surfers locally and from all over the world.

Jesús Domingo Boadas and Mariú Moya met at Playa Parguito in 1993.

Mariú was studying at the University of Zulia to become a preschool teacher, and she traveled to Margarita to visit her family on vacation. She helped her mother at the empanada stand as the “official fry cook”.

Jesús Domingo helped his family at the restaurant and gradually went on to assume more responsibilities as his father’s health deteriorated to diabetes. Whenever he had a break, he offered a cold coconut drink to the lovely Mariú. They exchanged glances from the restaurant and the empanada stand, but that was about it.

Minguito dropped from the University of Oriente, where he was pursuing food technology studies, because his father was sick and because the trip from the restaurant to the university was too long. So he decided instead to dedicate himself entirely to the family business. He was 25 years old.

They got engaged when Mariú earned her degree, and then got married in 1995. Valentina was born in 1996, and her sister Daniela in 1998. They could not ask for more. Life smiled at them.

On a typical Easter Friday at the beginning of the 21st century, Jesús Domingo would leave home at 6:00 a.m. and would go straight to the Conejeros market to buy fresh fish. Mackerel, sierra, red snapper, glasseyes, and grouper were the best sellers at the restaurant.

“Minguito, I’m heading to Margarita. What can you offer me today?” a customer would ask him over the phone.

“What would you like to eat?”

“How about fried snapper? Batter-dipped, deep-fried calamari?”

“Sure thing.”

The batter-dipped, deep-fried squid dish was the specialty of the house.

In addition to the family atmosphere and the meticulous visitor service, one of the perks of the restaurant was that patrons could eat and drink, and pay their bill later. Some even did so when they returned to their hometowns. Jesús’ father had set the tone. He was a serious, strict man of his word. From the very beginning, respect and trust between the restaurant’s staff and customers was the norm.

Kiosko El Caney was the venue of numerous international surfing competitions in the ‘90s and well into 2013. Minguito offered the organizers part of his beach front so that they could install a stage for the events. He provided them with showers, food and deserts, beer, cold coconut drinks, electric power, storage for their equipment, and the like. Whatever they needed. On one occasion, they set up an air-conditioned stage and, more recently, a Wi-Fi connection to broadcast a championship live. The events were covered by the regional and national media, and even by some international outlets, and had scores of sponsors.

As many as 2,000 people could flock to the beach on a single day. By noon, they had to close the road to the premises because there was no room for one more car. They could easily sell twenty cases of beer and serve eighty meals in less than twenty-four hours. They had five cooks who could barely keep up with diners’ orders.

In the following years, as the economic crisis worsened, they had no choice but to change the menu. They did not have as many customers as before, and the ones that they still did could no longer afford to eat and drink what they used to. Even long-standing customers would visit once a month only, instead of every Sunday. People began to order hamburgers instead of fried fish, and French fries, fried green plantains or salad sides instead of battered calamari. No one called Jesús on Sundays anymore to have a sun shade set aside for them: there were plenty.

They didn’t need five cooks, and two of them ended up leaving the country anyway.

So, Rosa and Marielba, Jesús Domingo’s sisters, had to take over. Never again would they have to prepare eighty meals in a single day. The restaurant barely filled to half its 10-table capacity. Long gone were the days when people had to wait to be seated.

According to the Nueva Esparta Tourism Corporation (Corpotur), about 2.5 million people entered the island between the months of January and October of 2014. By contrast, in 2019, the number of visitors was approximately 570,000 over the same period, roughly a quarter of the 2014 figure.

The 2020 Carnival weekend was very slow in terms of sales and number of visitors. Things had already gotten pretty bad when the COVID-19 quarantine and related restrictions were announced.

A mortal blow was dealt to the island’s restaurants, particularly to those located on beaches far from Porlamar, such as Kiosko El Caney, because fuel was scarce and because roads that connected the various municipalities were ordered closed to avoid the spread of the coronavirus.

According to the Nueva Esparta Chamber of Commerce, at the close of March 2020, 73 percent of the businesses in the state had halted activities, and only supermarkets and pharmacies were actively operating. Remote working and delivery services were the only options available if they wanted to stay afloat, but none was applicable to a restaurant by the beach. No one would place an order of fried fish for home delivery, and even if someone did, it was almost impossible to make the trip to the customer’s house.

Family savings helped Kiosko El Caney get through the first months of confinement. Even if they were selling nothing, they still had to pay the salaries of the restaurant’s seven employees, all the more so considering that some of them were relatives.

Not a single day would pass without Minguito showing up at the restaurant.

At first, he would only stay for a couple of hours and bring the watchmen the food that Mariú had prepared for them, and he would feed Blanquita and Shakira, the dogs they had rescued and saved from starvation.

By noon, he was already back home, his head down, his gaze lost. For the first time in his working life, he had no source of income. There was no way for him to restart operations because the beaches had been closed and the police removed those who dared to go there.

The restaurant that had provided for three generations of Boadas had been placed into a coma of sorts.

By early June, customers began to call Jesús Domingo asking if he could sell them beer, for there were not too many places where they could buy alcohol during lockdown. And to everyone’s good fortune, the restaurant’s warehouse was up to the ceiling with cases of beer that they had not been able to place. So, Jesús Domingo began to sell beer for takeout, very discreetly, though, and only in small amounts and to a few acquaintances, for authorities were enforcing compliance with regulations and they could not risk being caught.

Jesús Domingo used his daily trips to the restaurant to deliver the beers to his customers, who arrived in their cars and stopped strategically by the back of the premises to pick them up. In a commando-like operation, where everyone knew what they had to do and asked no questions, Jesús Domingo would quickly place the crates in the cars’ trunks and the clients would drive off with their merchandise. Payment was settled later.

When Mariú and Jesús Domingo felt their finances were finally improving, they were hit by the fuel shortages that had been plaguing the island since the beginning of the quarantine. The months of April and May were the worst, and the island looked like a ghost town.

According to a survey conducted by the Nueva Esparta Chamber of Commerce in June 2020, fuel shortages had significantly impacted 90 percent of the businesses in the sample. The huge drop in sales, the difficulties to operate, and the lack of staff were the most relevant consequences. For respondents, fuel shortages were 90 percent to blame for the decline in the number of customers. Fuel shortages had a greater impact on their bottom line than the constant power outages.

For a while, they managed to cope with the situation thanks to a close friend who provided them with gasoline, but in July they ran out. Minguito returned home from the restaurant with the last of the gas left in his tank.

“Dammit! I never thought it would come down to this! Those bastards, what they’ve brought us to!”

“Take it easy,” said Mariú.

“On top of the police controls, the blackouts, the fridge that keeps breaking down, now I don’t even have fuel. What am I going to do?”

His wife reminded him that, in spite of it all, they were in good health and alive during a pandemic, and that was reason enough to be thankful to God. As a cancer survivor, Mariú knew what she was talking about and would not stop repeating it to him, especially since the beginning of the quarantine. But, that day, her words of encouragement did not have the usual soothing effect.

Jesús Domingo went out into the house’s backyard and started exercising in a makeshift gym he had set up under a mango tree. It wasn’t the Gold Gym, of which he was a founding member, but it sure worked for him. He run several miles and lifted the weights he had made with plastic containers, cement and dirt. He did so many reps that the muscles in his arms were burning.

The following morning, he woke up early and set to work in the home garden he and Mariú had planted just a few months before, which was bearing fruits for the first time: bell pepper, cassava, pumpkin, and corn. He took a sweet chili pepper and smelled it.

“Would you like to have a cup of coffee, honey?” asked his wife, her gentle voice taking his mind off his thoughts.

“Yes, I would, Mariú. Thank you,” he answered, looking at her and smiling, feeling blessed despite everything.

At noon, he took his daughter Daniela’s blue schoolbag and packed a couple of containers with lunch for the two watchmen and one with food for Blanquita and Shakira. He could not get there by car, so he took a borrowed bike they had in the house, strapped the bag on his back, and pedaled away from La Asuncion to the restaurant in Playa Parguito, a more than half-an-hour ride under the island’s sun, which is not that pleasant at that time of the day. Maybe he was thinking of his father and of his trips in his pick-up truck from La Asunción to water the coconut trees, back when there was nothing on the beach.

He made the trip every day for several weeks until they managed to find a solution to the fuel issue.

In September, quarantine restrictions were eased and things started to move. Although beer could be sold more openly, food sales did not take off.

The easing of lockdown restrictions came with strict and expensive biosecurity measures: they had to use disposable plates and cups, offer antibacterial gel in large amounts, and have a digital thermometer in place to take the temperature of customers without touching them.

Kiosko El Caney has not fully opened. The beachfront stretch is still closed. There are no sun shades or lounge chairs. People are served at the back of the restaurant. You can use the restroom, but that’s it.

Most of the people who visit Playa Parguito do not buy food or drinks. They just go there to relax, like the hippies in the ‘80s.

The power outages have not subsided, and there can be as many as five in a single day.

The little profit they make they reinvest in the restaurant, particularly to purchase beer. Jesús Domingo and Mariú are living one day at a time.

Loyal customers still go to Kiosko El Caney because they know they can swim at the beach and then have a couple of beers at the restaurant. And pay the bill later. It is a relationship built on trust, after all. They know the restaurant will be there for as long as the sea hits the white sand and the coconut trees give shade.

This story is one of the many written within the framework of the Tras los rastros de una historia [Trailing Stories] workshop that we offered to fifteen Venezuelan migrant journalists through our online El Aula e-nos platform in the 3rd year of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante training program.

2715 readings

I am a bachelor of communication and media from the Andrés Bello Catholic University and I have worked as a reporter and as a screenwriter. I currently perform organizational communications consultancy work and teach at the School of Communication and Media of the Andrés Bello Catholic University. #SemilleroDeNarradores [Seedbed of Storytellers].

It is beautiful to know about my uncles on a website, when I was looking for photos of playa parguito to show my friends where I live; I came across this beautiful report, I told my stories of holidays on this beach, followed by this report, I can’t be happier to show you this followed by a few photos, the best restaurant and the best people in town, keep it up Mariu, Minguito, Rosa and Marielba,

Just something to add, the cakes that Rosa makes are from another planet, if you go there you have to try them!!!

His nephew from ireland

Hy, Diego. Thanks to visite our site. There are many stories of venezuelans here 🙂