On April 15, 2020, residents of Churuguara town, a two-hour drive from Coro, state of Falcón, took to the streets to protest over gasoline shortages. They were repelled with tear gas. Edgar Flores, a 30-year-old lawyer and psychiatric patient, was among them. Several days later, law enforcement officials broke into his house and took him away.

On April 15, 2020, residents of Churuguara town, a two-hour drive from Coro, state of Falcón, took to the streets to protest over gasoline shortages. They were repelled with tear gas. Edgar Flores, a 30-year-old lawyer and psychiatric patient, was among them. Several days later, law enforcement officials broke into his house and took him away.

Edgar Flores had not worked as a lawyer for a long time. He was diagnosed with depression as a teenager, a condition that drives him to such state of paralysis that he stopped practicing law all together. But on April 22, 2020, at the age of 30, he felt the urge to prove that the accusations against him were false and set out to defend himself in an arraignment hearing before the Second Court of Preliminary Proceedings of the state of Falcón.

He was charged with incitement to hatred, conspiracy, resisting authority, and generic injuries by Prosecutor Elsy Villegas, just hours after having been taken into custody on Sunday, April 19, 2020 in the town of Churuguara, a two-hour drive from Coro, the capital of the state of Falcón, where he lived.

On the day of the hearing, Edgar persuaded his defense attorneys to allow him to present the arguments in his favor before the judge, the prosecutor, and the other two defendants. When his turn came, he took the floor.

When he finished, there was silence in the courtroom.

The prosecutor was impressed with the clarity of his arguments, the coherence of his ideas and the fluency with which Edgar had expressed himself. It was an impeccable defense, as she herself noted. And that was precisely why she refused to consider him a psychiatric patient, which he was. It seemed illogical to her that he would be.

“A person with mental illness could not have earned a degree and should be in an institution,” she said, in an effort to disprove, or rather downplay, his condition, despite its being supported by medical reports filed by Edgar’s defense counsels.

Judge Alejandra Mora hesitated for a moment. She even seemed moved when Edgar tearfully pleaded with her not to leave him incarcerated and begged her to let him see his daughter.

He felt that the judge was waiting for “an order from above.” And then, despite there being no legal reason to keep him in detention, she upheld the order that he kept on remand and instructed that he be performed a forensic medical examination.

Edgar was taken back to the barracks of the Scientific, Criminal, and Forensic Investigations Corps in Coro while he awaited trial and the results of the new psychiatric evaluation.

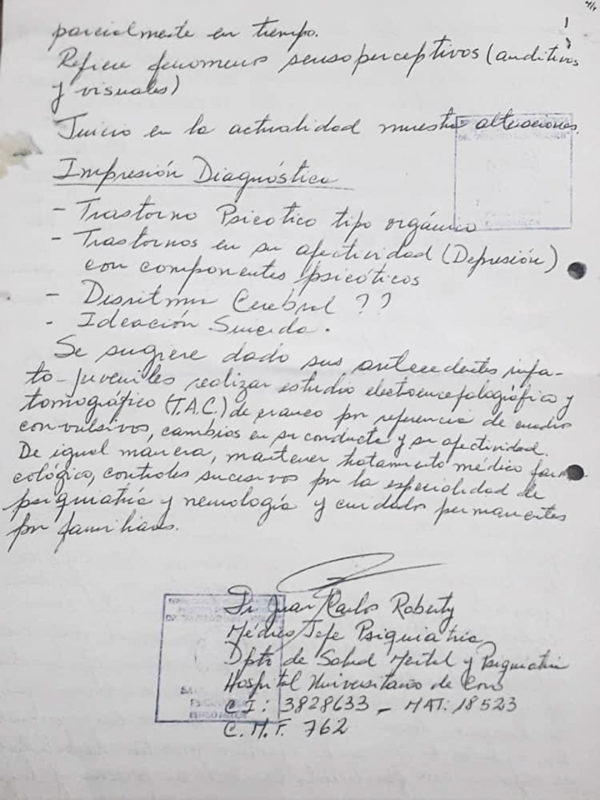

He has been diagnosed with organic affective syndrome with psychotic symptoms, severe depression, auditory and visual hallucinations, and suicidal ideation. When he was only six months old, he experienced febrile seizures that led to cerebral dysrhythmia, which is a disturbance or irregularity in the rhythm of the brain waves. And at the age of six, he sustained a fall that resulted in an encephalic traumatism, and he has been under permanent pharmacological treatment ever since. As a child, he would throw uncontrollable tantrums. He would become depressed. Sometimes he would wish his parents were dead or felt like hurting them, and that made him sadder and more confused.

Over the years, already in his teens, the outbursts of anger and the episodes of depression became more frequent. His mother, a very religious woman, blamed them on diabolical influences. But his father, a fine arts teacher, thought it was not normal that his 14-year-old son would show those symptoms, or that he would count his steps while walking, or that he washed his hands compulsively.

So, they took him to the doctor again. He was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Edgar learned that mental disorders ran in his family. His maternal great-grandfather had committed suicide, tormented by the idea that the world was going to end. A paternal uncle has symptoms of delusional disorder, and a paternal aunt died a schizophrenic.

He did not want history to repeat itself.

Fresh out of high school, Edgar enrolled in the University of Falcón to pursue law studies. He left Churuguara and settled in Coro. He lived in a student dorm, and many of his classmates made fun of him.

Now and again, he would fall asleep but he could not rest, haunted by nightmares.

His fits of rage drove away the girls with whom he tried to engage romantically, including the mother of his daughter.

Despite the many challenges he had to face, he did not quit, and in 2014, he was awarded his law degree. The day after his graduation ceremony, he was confronted with a question: “Now what?”

He could not find an answer, and that made him feel depressed.

In 2015, he chose to move to Costa Rica, where his sister lives. He got a job at a restaurant. However, although he had psychiatric support and treatment, he felt he didn’t belong there and returned to Venezuela after ten months. Then, in 2018, he moved to Argentina. He washed cars and made home deliveries, but he would soon realize that loneliness and cold weather are not good company for a depressive person.

So, he returned to Churuguara, again.

It was there where some villagers gathered on April 15, 2020 outside one of the two gas stations operating in town, waiting for fuel to fill their tanks. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, fuel shortages worsened, which had an impact on the economy of Churuguara.

Mayor Cástor Díaz arrived at the site in the company of some of the area’s military authorities. Producers, cattle ranchers, and drivers alike complained to him about the gasoline shortage. Díaz tried to calm them down. Edgar was also there. He urgently needed to fill up his fuel tank to travel to Barquisimeto, a three-hour ride, 99 miles away, where he was scheduled for therapy. The protest would soon turn violent. The mayor and the National Guard commander were beaten and shoved by the angry mob. Edgar tried to prevent them from attacking Castor Diaz, whom he has known since they were boys. In fact, they are distant relatives.

To break up the brawl, the guards threw tear gas at the crowd.

People ran to their homes. And calm returned to Churuguara.

Four days later, at 4:00 a.m., Edgar heard some voices. Only this time he was not delirious: a mixed team of the CICPC and the National Guard had broken into his house, where he lived with his parents and his daughter Miranda Sofia. The officers smashed down the entrance door. It suddenly dawned on him that he was the one they were looking for, so he frantically ran to a hilly area near the house.

He was terrified. He heard a dog barking insistently, then a gunshot, and then the animal’s muffled howl. They had killed the animal so it would shut up.

Although he was quite frantic, he thought there was no point in trying to escape, so he stopped running, returned home, and crawled under a bed.

That’s where the cops found him when they lifted off the mattress.

“Get out, you fucking bastard, or we will shoot you!” the officers shouted as they hit him in the abdomen and the ribs.

And they took him away.

The scene was the same in the homes of two other people who had been implicated in the events. On the way from Churuguara to Coro, the police accused them of promoting riots with funding from Leopoldo López, a leader of the Popular Will party.

The thoughts of death that have plagued him since he was a child came back pounding unto Edgar’s head. He thought they were going to kill him and entertained the idea of throwing himself out of the moving patrol car. He felt no fear. But when they sent him to the scientific police cells, it was a whole different story. He was to remain in custody for forty-five days, which is the statutory period for the investigations to unfold and the preliminary hearing to be held.

“Welcome to hell,” one of the police officers greeted him.

He could not breathe and he could not sleep.

At night, he would stare at the bars of the cell he shared with other inmates. They heard him mumbling incoherently. Sometimes he would wake up not knowing what was going on or why he was there. It was as if he had suddenly lost his memory.

He tried to commit suicide twice. In his first attempt, he took more pills than prescribed; in his second, he tried to hang himself in the shower. Both times, he was rescued by his cellmates. “C’mon, man! Your case is not as bad as you think,” they would tell him, trying to convince him that he had not to worry too much, and that things would sort out and he would soon be released.

They also tried to calm him down when fear stalked him and the voices in his head would not stop. Many of the forty-three inmates, including those charged with rape and murder, sympathized with him. It was with them that he shared that tiny space, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, with no safety measures to prevent contagion.

Visits to prisons had been restricted because of the quarantine. Since it was costly and difficult for Edgar’s parents to travel every day from Churuguara to Coro to bring him food and medicines, they decided to move to the area to be closer to their son and provide him with whatever he needed.

Edgar’s dad would make the trip every single day to bring him his pills, but Edgar would not always receive them on time.

And he would shut down.

“Your theatrics won’t get you out of here,” some of the jailers would shout at him.

He took refuge in faith, the same faith his mother has clung to for years in search of a cure for his condition. He also reminisced of his 3-year-old daughter. Thinking of her made him feel free and temporarily removed him from his perennial sadness.

On June 30, 2020, having spent seventy-one days in prison, Edgar was released with an order to report to the court every forty-five days. The order was issued after Dr. Juan Carlos Robert, who was the head of the psychiatric area of the Coro Hospital, corroborated his clinical diagnosis in the forensic report the court had requested.

A month after his release, he learned that, in a future trial, he could be sentenced to 10 to 20 years imprisonment. He then remembered how dreadful prison was and some of his cellmates shaving their heads or cutting themselves in protest.

He went into his room, downed several pills, and began to feel short of breath. His parents found him just in time and had his stomach pumped immediately. He has also had panic attacks and delusions of persecution at the thought of the trial. But his faith in God and the medication he has been prescribed have helped him to free himself from the emotional prison in which he sometimes finds himself.

He inherited the artistic creativity of his father and tries to make the most of it.

Now, living in Coro with his parents and daughter, he combines graphic design with a small cheese business.

Edgar is well aware of his psychiatric condition. He has understood that acknowledging his illness can be good for him and for other people with the disease who, like himself, feel misunderstood. That is why he loves to spread his story.

And, of course, he would like to practice law again if the conditions were different.

Esta historia historia forma parte de La Emergencia Silenciosa, un proyecto editorial desarrollado por la red de narradores de La Vida de Nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

Esta historia historia forma parte de La Emergencia Silenciosa, un proyecto editorial desarrollado por la red de narradores de La Vida de Nos, en el 3er año del programa formativo La Vida de Nos Itinerante.

1698 readings

I am a journalist, fortunately, because I cannot see myself exercising any other profession. I am a correspondent for Crónica Uno and for the Press and Society Institute in Aragua. I am also an active human rights defender.

Un Comentario sobre;